By David Cunningham

Like many teachers, I intend to treat the upcoming 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington as an occasion to revisit Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famed “I Have a Dream” speech. Many of my students will, I expect, be deeply affected by Dr. King’s ability to impart a timeless quality to the “fierce urgency of now” that he associated with the Civil Rights Movement.

When celebrating King’s enduring relevance, however, we often neglect the implications of his message for issues that remain no less urgent today. So this year I also plan to focus on perhaps the speech’s most intimate moment, when King paused to address those on the front lines of the freedom struggle. Noting how his fellow civil rights activists had been victimized in ways both vicious and shrewd, he referred to them as “veterans of creative suffering.”

That the sanctions of Jim Crow were borne so “creatively” was a tribute to the activists who met brutality with non-violent resistance, nullifying segregation’s moral standing and thus much of its power. But, as King understood well, segregationists worked creatively too, finding new ways to impose suffering on those who threatened their way of life. Considering the breadth, depth, and sophistication of the system that resisted civil rights advances allows us to appreciate the enormity of the Civil Rights Movement’s accomplishments as well as to recognize the ways in which those achievements remain under siege. Digging deep to comprehend the inner workings of civil rights opponents enables us, as we celebrate the promise and rewards of Dr. King’s dream, to also more clearly grasp the challenges associated with its fulfillment.

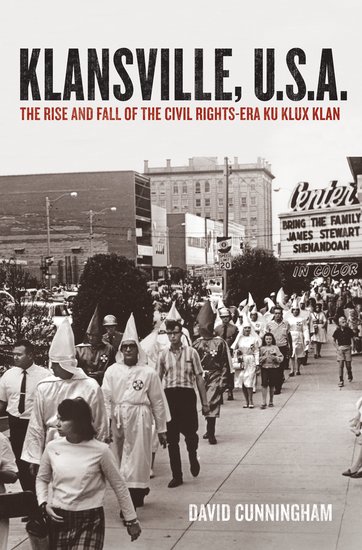

The hallmark of Jim Crow-style racial control was that its most visible agents — epitomized by the white hoods and burning crosses of the Ku Klux Klan — were undergirded by a full spectrum of “respectable” state and local leaders, from governors on down to school boards. Such comprehensive efforts meant that broad swaths of the white citizenry perpetrated and tolerated a campaign to maintain segregation.

As targets of that campaign, would-be black voters across the south were regularly stonewalled by local registrars, in myriad and sometimes inventive ways. (Sociologist Charles Payne notes that one woman in the Mississippi Delta reported being rebuffed when she was unable to compose on the spot an original poem about the Constitution.) City Councils passed dozens of ordinances limiting protestors’ ability to gather in public spaces, and privatized or closed playgrounds and pools rather than desegregate them. State legislatures established and funded Sovereignty Commissions to spy on civil rights agitators. Newspaper editors eagerly published activists’ names and addresses, an open invitation to physical reprisals. White business and civic leaders joined Citizens’ Councils, which regularly engineered firings and other economic sanctions. Such multifarious efforts were repeated in hundreds of combinations throughout the 1960s, a fact obscured in accounts that reduce segregation’s defenders to KKK types and stereotyped caricatures of marginal and ill-educated rural sheriffs.

While much has changed since 1963, those forces of resistance did not melt away. Social scientists have demonstrated how, as court decisions over the past two decades have loosened federal oversight over school desegregation plans, changes in local districting policies have led to a steady re-segregation of public schooling. Protests over the recent acquittal of George Zimmerman demonstrate the pervasiveness of the sentiment that self-defense statutes can intersect with racial prejudice to allow young black men to be unjustly murdered without sanction. Following a similar logic, legal scholar Michelle Alexander points to widening racial inequities in mass incarceration, indicting the system as the “new Jim Crow.”

Most palpably, the battle over how — or whether — to heed the lessons of the civil rights struggle played out earlier this summer with the Supreme Court’s striking down of Section 4 of the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts characterized that section’s voting rights provisions as “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.” The court’s dissenting opinion, penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, sharply rebuffed that assertion, emphasizing the “second-generation barriers” that seek to reconfigure discriminatory racial practices.

As in the 1960s, the power of these barriers resides in their insidious nature, with seemingly benign bureaucratic wrangling accomplishing what outright intimidation often cannot. As Justice Ginsburg contends, failing to grasp why voting rights protections against such measures have succeeded condemns us to repeat history.

This is precisely the history that Dr. King worked tirelessly to overcome. So as we celebrate his ideal of the “beautiful symphony of brotherhood,” remain mindful too of his admonition that we not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” That urgency remains as fierce now as when King stepped to the lectern on the National Mall fifty years ago.

David Cunningham is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and the Social Justice & Social Policy Program at Brandeis University. Over the past decade, he has worked with the Greensboro (N.C.) Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the Mississippi Truth Project, and served as a consulting expert in several court cases. He is the author of Klansville, U.S.A: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-era Ku Klux Klan and There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence. His current research focuses on the causes, consequences, and legacy of racial violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.