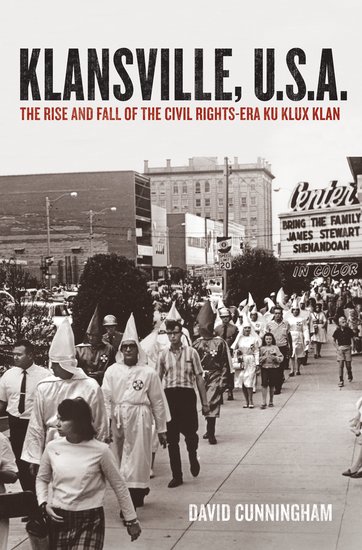

How can mainstream institutions and ideals subsume organized racism and political extremism? Why did the United Klans of America (UKA) once flourish in the Tar Heel state? From lax policing to a lack of mainstream outlets for segregationist resistance, a variety of factors led to the creation of one of the strongest and most complex Ku Klux Klan (KKK) groups in America — and a dramatic conservative shift in North Carolina. We sat down with David Cunningham, author of Klansville, U.S.A., to discuss the rise and fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan.

Why was the KKK so popular in North Carolina?

Two factors were important. First, the state’s klan leadership — and in particular its top officer, “Grand Dragon” Bob Jones — had the ingenuity and capacity to mount massive rallies every night in the state. Hundreds — and sometimes thousands — of spectators would come out, buy refreshments and souvenirs, listen to live music from the KKK’s house band Skeeter Bob and the Country Pals, hear a full slate of klan orators, and watch the climactic burning of a 60 or 70 foot high cross. This skewed county fair atmosphere was compelling theater, and a highly effective recruiting tool.

The second factor related to the flipside of North Carolina’s pronounced moderation with civil rights. In places like Mississippi or Alabama, committed segregationists could count on militant support from a full spectrum of state and local officials — from governors on down to school boards — and the KKK therefore had a narrow appeal, primarily among those who believed that violence was the only answer to civil rights challenges. In North Carolina, where political officials were clear that they didn’t agree with civil rights reforms but would abide by federal law, the klan became the primary conduit for those who sought to defiantly maintain segregation. This meant that, while the group certainly attracted its share of violent members, it also appealed to those who sought out a civic outlet that insulated them from changes to the racial order.

What led to the KKK’s abrupt and rapid decline in the late 1960s?

While the declining fortunes of Jim Crow-style segregation made the klan’s efforts seem increasingly futile and anachronistic, the fall of the civil rights-era KKK was predominantly a policing story. In North Carolina, state officials had always spoken out against the klan but hadn’t ever engaged in actions that would proactively hinder the group’s efforts to organize and terrorize its enemies. When a congressional committee held hearings on the KKK in late 1965, the state’s status as “Klansville U.S.A.” was splashed across the national headlines. This led to an about-face in North Carolina’s policing efforts. The Governor appointed an “anti-klan” committee to strategize about how to solve its KKK problem, and soon after state police began arresting klansmen on violations large and small, court injunctions prevented the klan from holding rallies in many communities, judges began sentencing klansmen for infractions that would have been ignored earlier in the decade, and both the state police and FBI began more aggressively deploying informants to create infighting within klan units that sapped the group of its resource base. While the press emphasized how disgruntled KKK members were abandoning a laughably crude and irrelevant organization, in truth the Carolina Klan was a sophisticated outfit whose momentum was halted only by an equally dedicated and coordinated anti-klan policing campaign.

What does the KKK’s history tell us about the civil rights movement?

Fifty years ago, while Dr. King was delivering his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the Mall in Washington, DC, the KKK was barnstorming around North Carolina, holding its first rallies and attracting two or three thousand spectators each night to protest the rising civil rights tide. When King came to Raleigh, the state’s capital, three years later, a thousand robed klansmen gathered to protest his speech. Talking to reporters afterward, he asked how the state that prided itself as the most liberal in the South could also have the largest KKK. We know that the Civil Rights Movement story remains important, and this is a key component of it — part of the mosaic that continues to shape race relations in the United States today.

What was it like talking to these former KKK members as you researched your book?

These conversations ran the gamut, from unreconstructed defenses of the klan’s mission, to strong rejections of the KKK’s principles, to nostalgic reminiscences about the camaraderie and “good fun” that members enjoyed. Two interviews in particular stand out. The first was with Robert Shelton, who as the United Klans of America’s “Imperial Wizard” was the most influential KKK leader of the era. Shelton had been put out of the KKK business by a landmark Southern Poverty Law Center lawsuit in the 1980s, and by the early 2000’s had adopted a Burger King near his Alabama home as a sort of ad hoc headquarters for him and “his boys.” He agreed to meet me there, and arrived in a big powder-blue Lincoln Town Car with a defiant “Never” license plate displayed in front. He bragged about working out a deal with the manager for cheap coffee in return for keeping the restaurant full. The disjuncture between his persona and the setting, I think, says a lot about the klan’s declining fortunes since the 1960s.

Another interesting interview was with George Dorsett, the Carolina Klan’s most popular and fiery speaker in the 1960s. Late in his life, both his charisma and his stridency remained evident as he regaled me with Biblical justifications for racial separation. He also told me about his work as an FBI informant throughout much of his klan tenure. I had previously seen documentation of his recruitment by the Bureau, and also had learned about his partnership-of-sorts with his local handling agent. But what struck me was his retrospective view that the FBI was working for him, which isn’t entirely inaccurate if you consider how he was able to protect his role as the KKK’s most successful fundraiser while on the Bureau’s payroll.

What is the KKK’s legacy today?

In my view, the KKK continues to embody two opposing realities. The first relates to the tragic continuities associated with klan activity in the South. My colleague Rory McVeigh and I have found that communities where the KKK was active fifty years ago continue to this day to have significantly higher rates of violent crime than places where the klan never established a foothold. That sustained culture of violence is one aspect of the legacy of organized and sanctioned vigilantism. But the KKK’s trajectory also epitomizes the great changes that have occurred in the South and our nation since the 1960s. In the 2008 election, Barack Obama became the first Democratic presidential candidate in more than three decades to win North Carolina. From Klansville, U.S.A. to the state that cemented the election of our first African-American president, all in less than fifty years — a remarkable transformation indeed!

David Cunningham is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and the Social Justice & Social Policy Program at Brandeis University. Over the past decade, he has worked with the Greensboro (N.C.) Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the Mississippi Truth Project, and served as a consulting expert in several court cases. The author of Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan, his current research focuses on the causes, consequences, and legacy of racial violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The Klan lost out because they bought into the right wing capitalist lies instead of pursuing radical pro white working class struggle.They were absorbed by the SOUTHERN STRATEGY of the Republican party.Which was always a fraud.

U.S. Insurgents will not make that error.

Fascinating history. I’d be careful about the ascription of “legacy” effects, however, as causation is hard to pin down. Is violence in a given location higher because the Klan had once been active there, or did high propensity for violence predate, and possibly promote, establishment of the Klan? We don’t really know.

[…] A Congressional investigation in 1965 found that North Carolina had the most active chapter of what […]