Poor Pilgarlic and his plight

The post on pilgarlic appeared on 13 June 2018. I knew nothing of the story mentioned in the comment by Stephen Goranson, but he always manages to discover the sources of which I am unaware. The existence of Pilgarlic River adds, as serious people might say, a new dimension to the whole business of pilgarlic. Who named the river? Is the hydronym fictitious? If so, what was the impulse behind the coinage? If genuine, how old is it, and why so called? What happened in 1883 that aroused people’s interest in that seemingly useless word?

On the same day, an old friend sent me a link to the website that listed synonyms for “masturbate.” I am well aware of the extensive vocabulary of sex, for I have written the etymology of the F-word and of a few other words belonging to the same “semantic field,” but I could not imagine that people had invented over a hundred phrases for the universal but uninspiring activity, euphemistically called self-abuse. Few of those phrases struck me as ingenious, and even fewer are funny. But I could not help noticing at least five among them that seem to support my derivation of pull ~ pill garlic: pull the carrot, cuff the carrot, slay the carrot, stroke the carrot, and buff the banana. Sure enough, pull is not the same as pill ~ peel, while carrot and banana fit the situation better than garlic. But Chaucer’s phrase seems to have been associated with the image of a bald head, to which the glans is often likened. Also, unprotected sex (“barebacking” in the gentle parlance of modern speakers) is sometimes called going at it bald-headed. And yes, I do think that Chaucer’s phrase was “incredibly obscene.” What would you say about something like “and he spent the whole night j**king off”? Pretty gross, I believe. You may be an admirer of Bakhtin’s carnival theory or have reservations about it, but the fact remains that Chaucer’s, Rabelais’s, and Shakespeare’s obscenities were exactly that.

And here is one more note on a related theme. (I hope my comments have not hurt anyone’s sensitivities.) In my rather large databank of idioms, I have a letter from Notes and Queries (1896, Series 8/IX: 187) in which the correspondent wondered what the odd phrase he had heard could mean: “It stands stiff, and but’s a mountain.” I am sure it is butts, not but’s, with the whole being not an idiom but a jocular description of sex. Most probably, quite a few people guessed correctly and felt amused by the writer’s innocence. That may be the reason for the lack of responses. On the other hand, the editor did not see the light, for otherwise he would not have printed the query.

Another look at “mad hatter”

“Mad as a hatter” was posted on 24 January 2018. I argued that “madness” could not be hatters’ occupational disease. Later, I remembered the expression blue devils “deep melancholy” and decided to say a few words about it. Not much is known about the origin of that phrase (blue devils are, apparently, the devils that cause depression), but E. Cobham Brewer, for years the main authority on the origin of idioms, discussed it in his Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and wrote: “Indigo dyers are especially subject to melancholy; and those who dye scarlet are choleric. Paracelsus also asserts that blue is injurious to the health and spirits.” The reference to indigo dyers should I think be dismissed, even though some imaginary or real tie between melancholy and the color blue exists: we feel “blue,” when we are sad (hence the blues, though forget-me-nots don’t make anyone sink into a depression). The same should be said about the idiom to be in a brown study, that is, absorbed in one’s thoughts and, at least formerly, troubled by such thoughts (see the post for 22 October 2014). The important thing is to disregard spurious links to professions.

I have received two letters about the most recent post on emotions. Today I’ll answer both and perhaps stop. If I find enough to add to my “gleanings” in June, I’ll write a sequel next week.

A small heart and courage

(See the previous post, June 27, on fear).

The first question runs as follows: “I was amused by the notion that a small heart is a sign of valor because it has little capacity for bleeding. Was this idea popular in the Middle Ages?” I know it only from The Saga of the Sworn Brothers. The great Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness, in his ironic and passionate novel on the themes of that saga (in the original it is called Gerpla, and in English Wayward People, but the title means approximately “mock heroics”), did not miss that detail. Other than that, all I can remember is the scene from The Lay of Atli, one of the songs included in The Poetic Edda. The hero Gunnar sees the heart cut from a slave’s breast and recognizes it for what it is, because it trembles, while his intrepid brother Högni’s heart, also presented to him, does not tremble at all. (This episode is also recounted in Chapter 37 of the Saga of the Völsungs.) Nothing is said about the size of those hearts, and I don’t know the origin of the belief celebrated in that heroic poem.

The second letter came from a correspondent who noticed my phrase between the Devil and the blue sea and asked where it came from. To me it came from the same source as blue devils, namely, my database of English idioms, and I sent the correspondent my references. But perhaps someone else will be interested in what I sent her. Here are two ideas on the origin of the phrase, as given in my sources. “The expression is made use of by Colonel Munroe in his Expedition with Mackay’s Regiment (London, 1637). In the engagement between the forces of Gustav Adolphus and the Austrians, the Swedish gunners, for a time, had not given their pieces proper elevation, and their shots came down among Lord Reay’s men, who were in the service of the King of Sweden. Munroe did not like this sort of play, which kept him and his men, as he expressed it, between the devil and the deep sea.” The other explanation known to me smacks of folk etymology: “It has been suggested that the phrase was adopted, if not originated, by the Royalists in allusion to Cromwell, ‘the deep C’, the relationship of the devil to deep ‘C’.”

The Way We Speak

This is from The New York Times: “…only a handful of judges from that era remain on the bench.” Is handful a collective noun? I wonder whether we are dealing here with the ineradicable American agreement of the type the mood of the tales were gloomy (this is a sentence from an undergraduate paper I always use as my parade example) or with the predominantly British use of the plural with collective nouns, as in the royal couple were seldom seen together, the team were in several towns, the Government are engaged in disputes and wars, and the like. This usage is very rare in American English (except for such noncontroversial cases as police and cattle and occasionally public). Since handful hardly qualifies for a collective noun, our mood should probably remain gloomy.

Featured Image: Between the Devil and the blue sea. Image credit: General view of Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack on 7 December 1941 via the U.S. Navy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

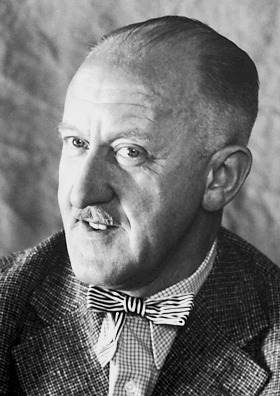

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Though it may appear in some later description of the event, “between the devil and the deep sea” does not seem to appear in the EEBO copy of

Monro his expedition vvith the vvorthy Scots Regiment (called Mac-Keyes Regiment)… (London, 1637).

Handful is a perfectly good quantifying noun, meaning ‘a small number of’, and number routinely takes either singular or plural agreement: a number of walls has/have fallen down.

Howdy, Anatoly,

I don’t know if you noticed my earlier note re my Middle English colleague’s comment that the text referenced was probably not by Chaucer. I just wondered whether you had better information on that.

I’ve never heard “between the Devil and the deep sea” — the rhythm is wrong — I’ve always heard “the deep blue sea”. It clearly belongs to the family of expressions like “between a rock and a hard place”, “between Scylla and Charybdis”, etc.

–Rudy

Have you seen some of the hats designers put out, that affluent fashion victims wear? Those hatters gotta be mad, tell ye that.

To specialize in hatting, not a mere tailor, you have to –. no, not be mad — you need wealthy customers and custom designs. The quirky, queer mannerism part of fashion shows must have been part of that as much as it is now.

It’s fab-u-loush, darling.