My database on please the pigs is poor, but, since a question about it has been asked by an old and faithful correspondent, I’ll say about it what I can. Perhaps our readers will be able to contribute something to the sought-for etymology.

When a word turns out to be of undisclosed or hopelessly obscure origin, we take the result more or less in stride, but it comes to many as a surprise to hear that the circumstances surrounding the emergence of an idiom are beyond reconstruction. In this blog, I have discussed quite a few puzzling phrases (it is raining cat and dogs, pay through the nose, kick the bucket, by hook or by crook, whip the cat, it makes nine tailors to make a man, to put a spoke in someone’s wheel, and so forth), and, although sometimes I ventured to share the opinion that seemed the most reasonable to me, I could never insist on it: the situation in which this or that picturesque phrase was coined happens always or nearly always to be forgotten. Our ignorance is especially irritating because words may be millennia old, while our idioms, unless they are so-called familiar quotations from Classical antiquity or translations of Greek and Latin adages (those people could coin wise sayings and aphorisms with the ease incomprehensible to us), rarely antedate the seventeenth century. Metaphors (as in whip the cat and their likes) in our languages are in general post-Renaissance phenomena.

In the phrase an’t please the pigs, an is an obsolete synonym of “if.” Unexpectedly, “if (should) it please the pigs” means “if circumstances allow; Deo volente, that is ‘with God’s will’”. Why? Where do pigs come in here? Today, hardly anyone uses this phrase, and not many people know it. Yet it is included in all big dictionaries, none of which offers an explanation, while sometimes pointing out that the old conjectures make little sense. Even the indomitable E. Cobham Brewer did not risk a hypothesis. My database on please the pigs spans the period between 1780 and 1884, with most contributions going back to 1852.

Since pigs in please the pigs makes so little sense, it has been suggested time and again that the word stands for pyx or pixies, or piga. A Pyx is a container in which the reserved Eucharist is kept. The change from Pyx to pigs might have occurred, given the militant anti-Catholic mood of the Reformation, but no facts bear out this etymology, and the entire hypothesis seems most unlikely. Pixies, the second candidate, are well-known creatures of folklore. Though they may lead astray a wayfarer (who will then be pixie-led), unlike so many other figures of popular imagination, they are usually not malicious, and there seems to be no reason why they should be or have been “pleased,” propitiated, or gratified. The change from pixies to pigs would also be hard to account for. Finally, Old Engl. piga “girl, maiden,” with reference to the Virgin, is a ghost word. Danish pige indeed exists, but its English cognate does not. And once again, such a sacrilegious change would be beyond comprehension.

There is a sizable body of legends about how people wanted to build a church in a certain place, but some animals intervened, and, as a result, the construction site was changed. One such legend concerns Winwick, Lancashire. The parish church “stands near that miracle-working spot where St. Oswald, king of the Northumbrians, was killed. The founder had destined a different site for [the church], but his intention was overruled by a singular personage….” The foundation of the church was laid. Yet “the approach of night brought to pass an event which utterly destroyed the repose of the few inhabitants around the spot. A pig was running hastily to the site of the new church; and as he ran he was heard to cry to scream aloud ‘We-ee-wick…!’ Then, taking up a stone in his mouth, he carried it to the spot sanctified by the death of St. Oswald, and thus employing himself through the whole night, succeeded in removing all the stones which had been laid by the builders…. Thus the pig not only decided the site of the church, but gave a name to the parish. In support of this tradition, there is the figure of a pig sculptured on the tower of the church, just above the western entrance….” The author of the article asks: “May not the phrase please the pigs have originated in the above tradition?” I find the plot familiar, the story entertaining, but the etymology fanciful.

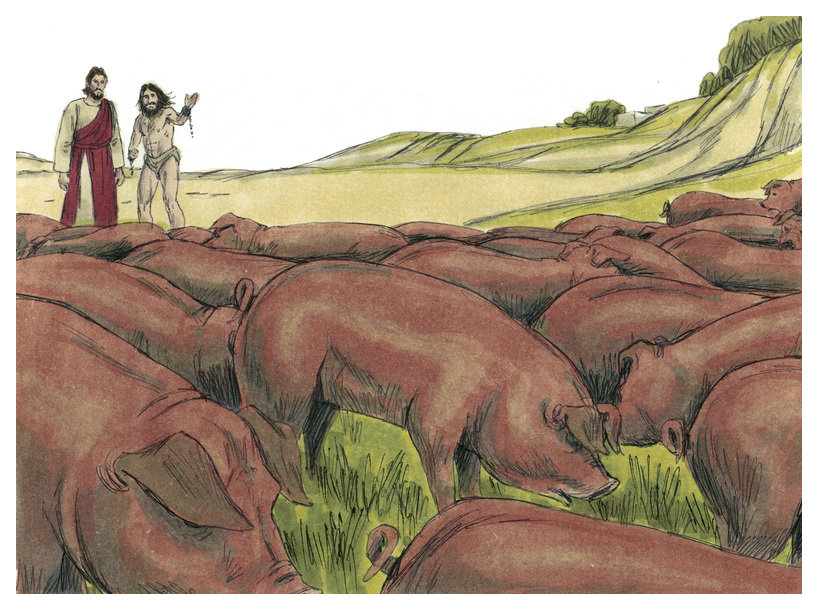

Perhaps the following observation, made in 1850, deserves attention. Alfred Gatty (1813-1903), vicar and an author, quoted the sixteenth-century Protestant martyr John Bradford. Here are a few of Bradford’s pronouncement’s: “And so by this means, as they save their pigs, which they would not lose (I mean theri worldly pelf), so they would please the Protestants, and be counted with them for gospellers, yea, marry, would they”; also: “Now are they unwilling to drink of God’s cup of afflictions… lest they should love their pigs with the Gergenites,” and: “This is a hard sermon: ‘Who is able to abide it?’ Therefore, Christ must be prayed to depart, lest all their pigs be drowned. The devil shall have his dwelling again in themselves, rather than in their pigs.” The biblical reference is to the pigs of Gergesenes (Mark VIII: 28 and the following). As we can see, there have been pious and impious pigs in history.

Vicar Gatty wrote: “These and similar expressions in the same writer without reference to any text upon the subject, seem to show, that men loving their pigs more that God, was a theological phrase of the day, descriptive of their too great worldliness. Hence, just as St. Paul said ‘if the Lord will’, or as we say ‘please God’, or as it is sometimes written, ‘D. V.’ [= Deo Volente], worldly men would exclaim ‘please the pigs,’ and thereby mean that, provided it suited their present interest, they would do this or that thing.”

I don’t think this explanation sounds too convincing, but there may be something in it. In any case, it sounds much more interesting than references to pixies and Pyx. A minor problem with our idiom about which Alfred Gatty wrote in 1850 that it is “too vulgarly common not to be well known” to the readers of Notes and Queries but which now seems to have fallen into desuetude concerns the alliteration (please the pigs). It happens only too often that in such phrases the second word is chosen for the sake of the euphonic effect.

Those who won’t be satisfied with the material presented above are advised to mediate on the origin of the phrase to save one’s bacon and the pub name pig and whistle, and remember that, however hard etymological research may be, pigs, contrary to conventional wisdom, occasionally fly.

Featured Image: Can’t they fly? Yes, they can. Image credit: “Pigs Fly Funny Hog Piggy Wings Pork Swine Hoof” by DigiPD. CC0 via Pixabay.

toly Liberman is the author of

toly Liberman is the author of

It may have to do with Saint Anthony and his reputed rapport with pigs, and his helper, called “Tantony” pig.

“… however hard etymological research may be, pigs, contrary to conventional wisdom, occasionally fly.”

Anatoly,

You can put lipstick on a pig, but you can’t hide the pig in your lipstick.

Constantinos

The St. Anthony connection is claimed in Gentleman’s Magazine, 1790, pages 1086-7.

St. Paul’s and St. Anthony’s were two very old schools in London. Anthony’s won many academic competitions.”The story of St. Anthony preaching to the pigs is too well known to merit repetition here…this saint was always pictured with a pig following him…the scholars at St. Paul’s nick-named their rivals St. Anthony’s pigs; who, in return, derided them with the appellation of St. Paul’s pigeons…. From this circumstance alone arose the saying of “an it please the pigs”;….” The word “alone” may be an exaggeration, but the Anthony and pigs association may be ineluctable.

For more context:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101076879939;view=1up;seq=552