Battles, butchers, and tyrants

CULLODEN. The battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746 between the forces of the Catholic “Young Pretender” Charles Edward Stuart, who was at the head of the Jacobites, and those of the government, led by Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland. Charles Edward is remembered in English history as Bonnie Prince Charles. His army lost the battle, and he died in exile. (Just for information: the duke turned 25 on the day before the battle; his opponent was 26; they were cousins.) Immediately after the battle, rumors circulated that the commander of each side instructed his followers to give the enemy no quarter. The “butcher duke” supposedly wrote his order on the back of a playing card. (See more about this card in last weeks’ post.) No authentic documents or cards confirming the order have been found. Moreover, there is a print, dated 21 October 1745 (that is, published half a year before the battle) that represents “the Pretender attempting to lead across the Tweed a herd of bulls laden with curses, excommunications, indulgences, &c. &c. &c. On the ground before them lies the Nine of Diamonds.” Nothing is said about the possible symbolism of the card, but, apparently, it has something to do with “the curse of Scotland” and suggests that in 1741 the connection between the nine of diamonds and the phrase was understood. The print is entitled “Briton’s Association against the Pope’s Bulls.” The pun on bull “animal” ~ bull “papal edict” is obvious. (We can see the Pretender grasping the horns of one of the group of bulls, while between his feet lies the nine of diamonds. Does another pun allude to taking the bull by the horns?) Some other early discussants confirmed the fact that the nine of diamonds had indeed borne the ominous name before Culloden, though no one knew why.

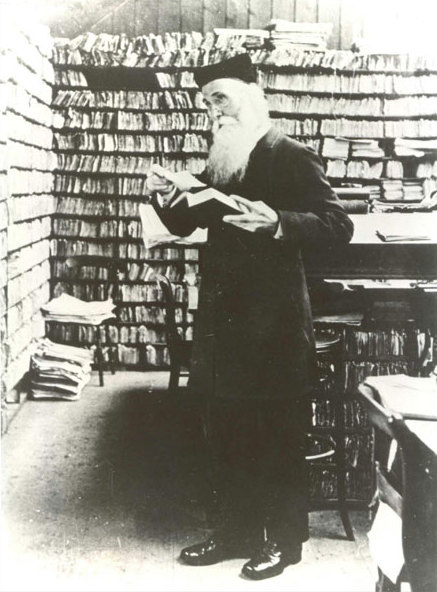

INTERMISSION: ENTER JAMES A. H. MURRAY (Notes and Queries, 8th Series/III, 1893, p. 367): “In Annandale’s ‘Imperial Dictionary,’ after mentioning, among many other ingenious and baseless guesses, a hypothetical connexion of the card with the Battle of Culloden, the author says, ’but the phrase was in use before.’ I shall be grateful to any one who will send me a quotation or reference for the ‘curse of Scotland’ before Culloden, 1745, or indeed before 1791, when it is mentioned in the Gentleman’s Magazine, p. 141. Jam[i]eson has no quotation, and knew it only as colloquial in the south of Scotland. I have not at present any grounds for thinking that the phrase is of Scottish origin.” Every line by J. A. H. Murray is precious. If I were a rich independent publisher, I would bring out two volumes: The Collected Letters of James A. H. Murray, Editor and The Collected Works of Frank Chance, Man of Letters, but, since I am neither a publisher nor a rich man, the books will never appear. To make amends, I have reproduced the letter about the curse of Scotland. As could be expected, Murray received many answers. As late as 1893, his team was obviously unaware of the publications in the Notes and Queries that appeared more than forty years earlier.

I have borrowed the next communication from W. A. Chatto’s entertaining book Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards, 1846 (as quoted by F. C. Birkbeck Terry, an erudite and one of the most active contributors to the Notes and Queries): “This card… appears to have been known in the North as the ‘Curse of Scotland’ many years before the battle of Culloden; for Dr. Houstoun, speaking of the state of parties in Scotland shortly after the rebellion of 1715, says that the Lord Justice-Clerk Ormiston [the note has Ormistone, which, as I understand, is wrong], who had been very zealous in suppressing the rebels, ‘became universally hated in Scotland, where they called him the Curse of Scotland; and when the ladies were at cards playing the Nine of Diamonds (commonly called the Curse of Scotland), they called it the Justice Clerk’.” This is useful information, but it sheds no light on why one particular card got such an ominous name.

Several main participants in the battle of Culloden denied any knowledge of the rumors. The noblemen of the Jacobite party Lord Balmerino and the Lord Kilmanrock, both attainted (as the action was called at that time) and beheaded after the battle (on 18 August 1746), asked another leading supporter of Bonnie Prince Charles, whether he had heard of any such order being made before the battle for giving no quarter to the Duke’s army. This exchange occurred on the day of their execution for high treason, and the doomed men would have gained nothing by lying. They affirmed that they had never heard of such orders. Lord Balmerino said “that he would not knowingly have acted under such order, because he looked upon it as unmilitary, and beneath the character of a soldier.”

No such statement from the duke is extant. The defeated Jacobites were treated with great severity, but no atrocities comparable to those only too well known to our contemporaries were reported. References to the behavior beneath the character of a soldier should seldom be taken at face value, for war is war and has always been attended by unspeakable cruelty. However, neither Prince William (despite the nickname butcher duke) nor the Pretender seems to have given such an order, let alone written it on the back of a playing card, and such a card hardly ever existed.

Today we know for sure that the phrase indeed predates the battle of Culloden, for as early as 1708, a book of questions and answers, titled The British Apollo (about which see my post for June 7, 2017), printed the following reply to the query about this phrase: “Diamonds as the Ornamental jewels of a Royal Crown, imply no more in the above-nam’ed Proverb than a mark of Royalty, for SCOTLAND’S Kings for many Ages, were observ’d, each Ninth to be a Tyrant, who by Civil Wars, and all the fatal consequences of intestal [sic: that is, internecine, internal] discord, plunging the Divided Kingdom into strong Discord, gave occasion, in the course of time, to form the Proverb.” This answer is reproduced with a photo of the page in Wikipedia at Curse of Scotland. Last week, I began my discussion with the hypothesis about every ninth king and need say no more about it.

At this stage of our disquisition, only one conclusion is clear. By 1708, the phrase had become so familiar that no one knew how it came about. The style of The British Apollo is always the same, and there is only one name for it: apodictic (no reasoning, no proof). The editors shed words of wisdom, and we are supposed to admire rather than question their omniscience. I noted this feature of their replies in my post, referred to a few lines above.

Next week will be devoted to the November gleanings, and in early December I’ll finish Act 2. We have one more important battle to discuss and draw some conclusions from our material.

Featured image credit: The Battle of Culloden, oil on canvas by David Morier. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

toly Liberman is the author of

toly Liberman is the author of

Just some observation from aside – layout of 9♦ on the card might differ.It can alternatively form 3 lines by 3 or can be depicted in 2 groups 4+5 diamonds where the upper part would resemble a Scottish Saltire. The Pope Joan might be a corruption from French yellow dwarf “nain jaune” game, related to jealousy fairy tale from 1698. 7♦ is the most important card there,but suite gathering seems similar. Some modifications taken into account (why is a mystery) the card game version seems plausible. Localized rule changes with some propaganda is a great combination for origin of the saying.

As far as I know, attainder (the declaration (by a judge after confession in open court, by a jury, or by Parliament) that a traitor or felon’s blood is corrupt, and therefore his property is forfeit and his heirs inherit nothing) is still called “attainder”, though it has been practically obsolete in the UK since 1798. The U.S. Congress is forbidden to pass bills of attainder. It is the thing which is obsolete, not the word.