By Paul Friedland

73 years ago today, Eugène Weidmann became the last person to be executed before a crowd of spectators in France, marking the end of a tradition of public punishment that had existed for a thousand years. Weidmann had been convicted of having murdered, among others, a young American socialite whom he had lured to a deserted villa on the outskirts of Paris. Throughout his trial, pictures of the handsome “Teutonic Vampire” had been splashed across the pages of French tabloids, playing upon the fear of all things German in that tense summer of 1939. When it came time for Weidmann to face the guillotine, in the early morning hours of 17 June, several hundred spectators had gathered, eager to watch him die.

Why was this to become the last public execution in France? In the days following Weidmann’s death, the press expressed a growing indignation at the way the crowd had behaved. A report in Paris-Soir, published the day after the execution but seemingly drafted in the heat of the moment, characterized the spectators as a “disgusting” and “unruly” crowd which was “devouring sandwiches” and “jostling, clamoring, whistling.” Before long, the government decreed the end of public executions, expressing its regret that such spectacles, which were intended to have a “moralizing effect” instead seemed to produce “practically the opposite results.” From now on, executions would take place behind closed doors.

The exuberance of the sandwich-eating crowd — however “disgusting” — seems like a rather thin pretext on which to base a radical change in the execution of justice. After all, spectators had been expressing their enthusiasm for, and snacking in the middle of, executions for a very long time. What made this execution different was the fact that it had been delayed beyond the usual twilight hour of dawn and there had been sufficient light for several startlingly clear photographs to be taken. Photographs soon appeared in magazines across the world, including Match and Life. Worse still, from the authorities’ point of view, someone had managed to capture the entire event on film.

But wasn’t the whole point of public executions that people should be able to see them? In theory, yes — or at least in the theory of exemplary deterrence bequeathed to western society by Roman law: that future crimes could be prevented through the spectacular punishment of criminals, striking fear in the hearts of spectators. In practice, however, matters had never been quite so straightforward. Medieval audiences weren’t particularly terrified by executions, tending instead to experience them as quasi-religious ceremonies, singing and praying together with the condemned. Early modern audiences, by contrast, tended to view executions as a form of entertainment. In 1757, for example, hundreds of thousands of spectators massed in the Place de Grève outside the Hôtel de Ville, desperate to watch the would-be regicide Damiens suffer unimaginable punishments over a period of many hours. Very far from being terrified, they showed up with binoculars and a variety of drinks and snacks, the equivalent of today’s movie popcorn. In the coming years, exemplary deterrence would be further complicated by a revolution in sensibilities which took a very dim view of anyone who delighted in the sufferings of others, making the very act of watching executions problematic.

To be clear, these newer sensibilities didn’t oppose capital punishment so much as the spectacle of it. And so began a long period in which government officials and public opinion still subscribed in theory to the notion that public punishment served the goal of exemplary deterrence, while in practice believing that anyone who could actually bring themselves to watch was beyond moral redemption. Writer Jean-Baptiste Suard expressed this paradox: “Unfortunately, it’s not on the wicked people, but rather on the sensitive souls, that the spectacle of punishments leaves the strongest impressions. The man whom one should most fear meeting in the forest, he’s the one who likes attending executions of criminals.”

Not only in France, but throughout the West, exemplary deterrence remained a sacrosanct principle of justice even while contemporary sensibilities essentially forbade the act of watching. From the mid-nineteenth century onward, governments across the globe began to find this situation untenable and made the decision to move executions behind closed doors. Most German states did so in the 1850s, Britain in 1868, and most American states around the turn of the 20th century. France, by contrast, initiated a very long game of hide-and-seek, with officials desperately seeking to limit the visibility of executions on one side, and spectators equally desperate to see them on the other. Guillotines were exiled to the outskirts of town; raised platforms were outlawed in the hopes of limiting spectator visibility; executions were performed with little notice and at the crack of dawn. But still the crowds came — thinner, to be sure, but always present. Only when spectators photographed and filmed the execution of Weidmann, offering the prospect of an infinity of spectators witnessing the event far into the future, did government officials finally acknowledge the futility of trying to make public executions invisible.

And then began a new period in the history of capital punishment, arguably the one in which most countries that still practice it now find themselves. Executions performed behind closed doors are still believed (in some vague and dimly understood way) to serve the goal of exemplary deterrence. If a tree falls in the forest, and no one is around to hear, apparently it does make a sound.

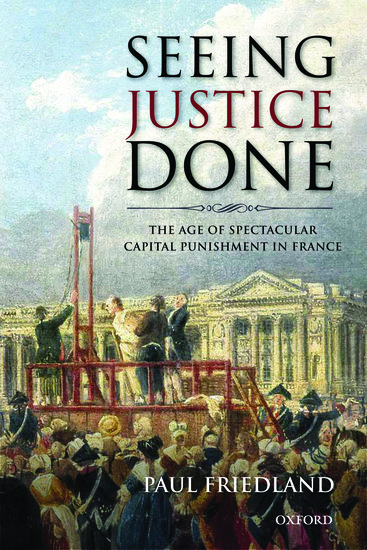

Paul Friedland is an affiliate of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, and currently a fellow at the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University (2011-2012). He is the author of Seeing Justice Done: The Age of Spectacular Punishment in France, which explores the history of public executions in France from the Middle Ages to the 20th century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

![Ten new books to read this Women’s History Month [reading list]](https://oupblog.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Floating-open-book-480x185.jpg)

[…] gathered behind a second cordon, not visible in this photograph. Roger-Viollet / The Image Works. LINK I watched with glee, while your kings and queens, fought for ten decades for the gods they […]