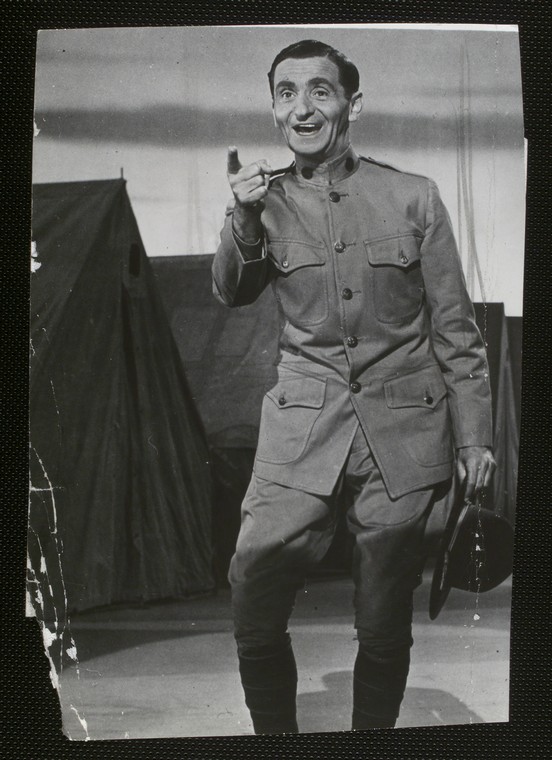

From singing for pennies on the Lower East Side to his own theater on Broadway, Irving Berlin had an amazing journey to American musical legend. To commemorate the birthday of this great American songwriter, we spoke with Jeffrey Magee, author of Irving Berlin’s American Musical Theater.

You write that Berlin saw his work as a “mirror” of the nation.

Berlin believed that “the mob is always right.” What does that mean?

Berlin held a mercilessly populist notion of his craft. He didn’t believe his work was good unless people wanted to sing it and buy it in the form of sheet music, sound recordings, or tickets to his shows on stage and screen. For him, songwriting was business, and art and commerce went hand in hand. I argue that this sensibility took root in his early experiences as an immigrant on the Lower East Side. And I develop the idea that it reflects what I call a “Lower East Side Aesthetic,” which holds a practical, even survivalist, view of creativity and entertainment as a job joining ambition, entrepreneurship, mercantilism, and, not least, craft.

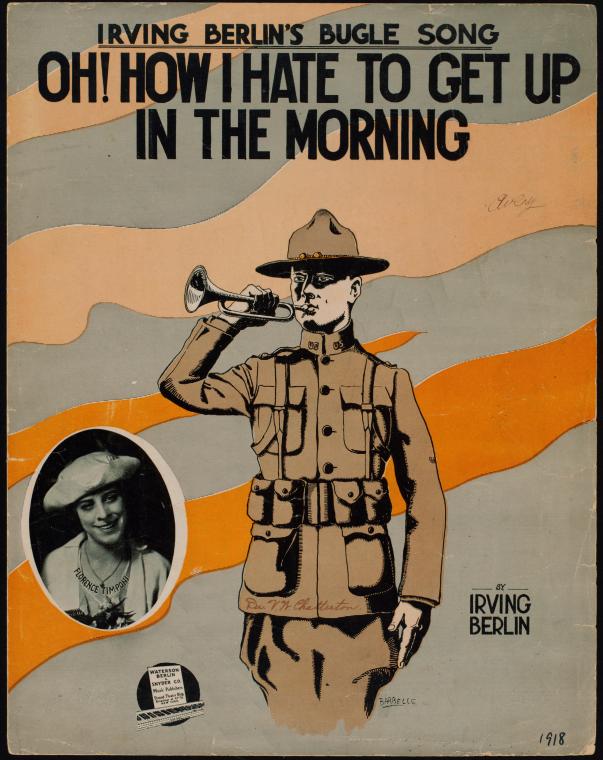

He named them: “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” “Say It With Music,” “Always,” “Blue Skies,” “How Deep Is the Ocean,” “Easter Parade,” “White Christmas,” “God Bless America,” and “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

Why were those songs his favorites?

In a statement when he named these songs, he equated “favorites” with “the ones that have won the widest acceptance.” In other words, he judged his songs not by his own standards but by the response of the “mob.” He once even declared that “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” was “terrible,” but it was a favorite because people liked it: they wanted to hear it.

Berlin made a distinction between a “composer” and a “songwriter.” Why? What’s the difference?

Berlin stands out in a small group of Americans between Stephen Foster and Stephen Sondheim who succeeded writing both words and music. So he called himself a “songwriter” and denied being a “composer.”

Which came first, words or music?

People know a lot of Berlin songs, but why not his musicals?

Theater stood at the center of Berlin’s world, and he wrote all or most of the score for some twenty shows across a half century. But just one of his shows has seen continuous productions since its premiere: Annie Get Your Gun, and that show is almost unique among his shows in its historical plot. For Berlin, effective musical theater had to be an event that spoke directly to the “mob” of the moment. He gave little or no thought to writing “masterworks” that would be performed years beyond their openings. The chief legacy of most of his shows has been the songs, but in recent years many of his earlier shows have been revived, and they continue to delight audiences.

Did Berlin have a favorite among his shows?

Yes, and it comes as a surprise to most people. It was his World War II soldier revue, This Is the Army, which opened on July 4, 1942, toured the country, went to Hollywood, then went overseas — ultimately playing for some 2.5 million military and civilian spectators in the U.S., Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and the South Pacific before its last performance in October 1945. Today, the Hollywood adaptation (starring Ronald Reagan) is the way people remember the show, if they remember it at all. But that film, which was one of the top grossing films in Hollywood in its day, overlaid a sentimental plot on top of a revue that aimed to capture the common ground between soldiers and civilians. Among Berlin’s papers, there is a mountain of material on this show. He had hoped to write a whole book about it.

Berlin’s papers? You had access to them?

Yes, mainly at the Library of Congress, where they’ve been housed since the mid-1990s. The Irving Berlin Collection there contains well over 600 boxes and some 750,000 documents. As I discuss in the book, there are musical manuscripts and lyric sheets, revue sketches, musical comedy scripts, orchestral parts, screenplays, scrapbooks brimming with newspaper clippings, photographs, business papers, financial and legal records, and correspondence — thousands of letters written to and from powerful and lofty figures including presidents and generals, show business personalities, and ordinary citizens expressing appreciation for Berlin’s work or good wishes for his family. The thing that struck me, above all, is that Berlin wrote a lot of music for the theater that has never been published, mostly because it exceeded the bounds of Tin Pan Alley’s conventional sheet music format. Meanwhile, the unpublished scripts allow for a clearer understanding of the context for which Berlin wrote musical numbers.

Is there any one discovery that stands out among all that stuff?

Why do the shows matter?

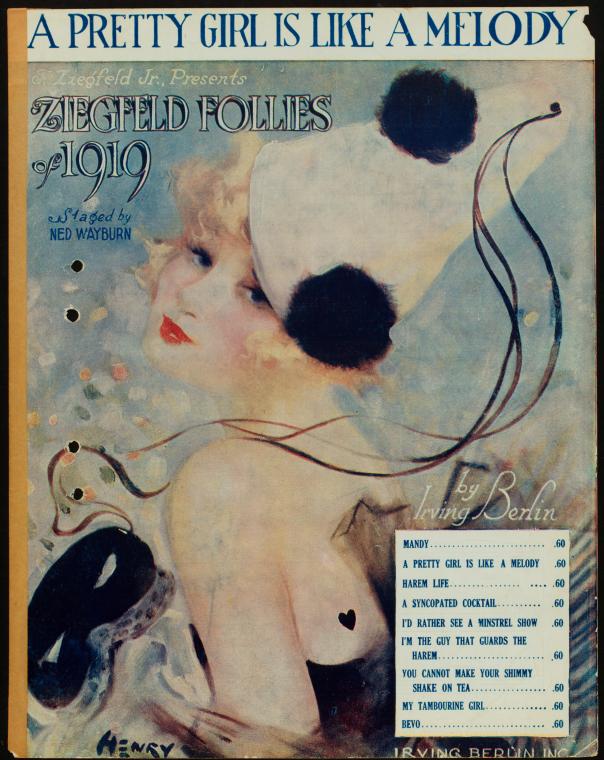

The shows reflect an omnivorous embrace of everything available on the American musical stage, not just musical comedy, but opera, revue, vaudeville, minstrelsy. They may be seen as a prism through which we can understand where this uniquely American idiom came from. He began writing Broadway shows three decades before Rodgers and Hammerstein joined up, at a time when his great ambition was to write a distinctively American opera in ragtime, so his work offers a microcosm of the Broadway musical in the formative years of the genre. Berlin was a particular master of the revue, which offered a sequence of songs and sketches linked by a common theme and refracted current events, people, music, and theater itself. The glorious age of the revue, the 1910s-20s period, has almost been lost to history, but Berlin’s papers help us to imagine what it was have been like. Alan Jay Lerner once wrote that “what Berlin did for the modern musical theatre was to make it possible,” and I hope readers come away with a sense of how that happened.

Jeffrey Magee is Associate Professor of Music and Theater at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and author of The Uncrowned King of Swing, winner of the Irving Lowens Award from the Society for American Music. He is the author most recently of Irving Berlin’s American Musical Theater.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Bless America” been well known at the time, it might have proved a significant challenger. But Irving Berlin’s song was invisible until 1938, when it was performed as a prayer for continued peace in the […]