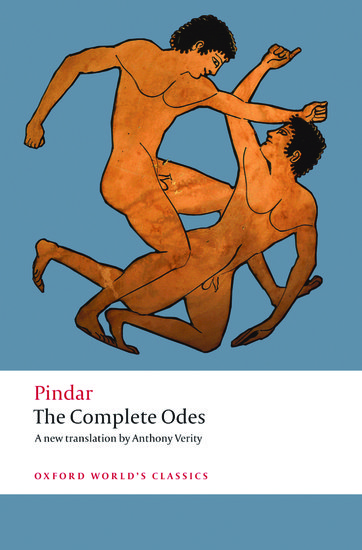

As the Olympic Games kick off tomorrow, Mayor of London Boris Johnson has ensured that London 2012 retains its ties to the ancient world. Trained as a classicist and fond of reciting Latin (particularly in debate), he commissioned an ode by Armand D’Angour in the style of the Ancient Greek poet Pindar, which was recited at the Olympic Gala at Royal Opera House on July 24th. Oxford University classicist Dr Armand D’Angour’s Olympic Ode will be installed at the Olympic Park in East London, but you can discover Pindar’s verses on the blog today. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction by Stephen Instone to The Complete Odes by Pindar, translated by Anthony Verity:

The victory odes are divided into Olympians, Pythians, Nemeans, and Isthmians after the four great ‘panhellenic’ games that were open to all Greeks. All athletics games in ancient Greece were part of a religious festival in honour of gods or heroes. The Olympic games were the oldest and most prestigious, held in Elis in the western Peloponnese in honour of Zeus. There had been a sanctuary to Zeus there even before the traditional date for the founding of the games (776 BC). Athletics competitions provided an additional way of honouring the god, the winner owing his victory to the help of the god and in consequence thanking the god. The festival lasted five days and took place, as nowadays, every four years. On the first day Zeus apomuios or ‘averter of flies’ was invoked to keep the sacrificial meat fly-free, and on the third day a hundred oxen were sacrificed to Zeus. The programme of events developed and changed during time.

In the fifth century, when Pindar was writing, there were

- three running events: the stadion (a sprint the length of the stadium), the diaulos (there and back), and the dolichos (twelve laps);

- a race when the runners wore armour and carried a large shield (there and back);

- boxing, wrestling, and the pancration (‘all power’, in which virtually any method of physical attack was permitted);

- the pentathlon (long jump, sprint, discus, javelin, and wrestling).

Most of these events had separate age-categories for men, youths, and boys. There were also horse an horse-with-chariot races held in the hippodrome. For a few Olympics there was a mule race (Olympian 6 is for a winner in this event); mules were bred in Sicily, and the Sicilian tyrants may have played a part in establishing this event. The Pythian games were held in honour of Apollo at Delphi. The programme was broadly similar to that of the Olympics, but included music competitions (for Apollo the god of music); Pythian 12 is for a winner in the pipe-playing competition. They were traditionally founded in 573, took place every two years at Nemea on the east of the Peloponnese. They were also in honour of Zeus. The Isthmian games, traditionally founded 582, also took place every two years. They were held in honour of the sea-god Poseidon at the Isthmus, the strip of land that then connected the Peloponnese with mainland Greece. In his victory odes Pindar generally refers to the god presiding over the games where the victory had been gained and sometimes the myth relates to the particular games (for example, in Olympian 1 the myth concerns Pelops who had a hero-cult at Olympia).

These four games formed a circuit for athlete, as the Olympics, World Championships, European, and Commonwealth Games do for some athletes today. A few outstanding athletes, such as Diagoras of Rhodes for whom Pindar composed Olympian 7, won at all four (like the British decathlete Daley Thompson who in the 1980s simultaneously held Olympic, World, Commonwealth, and European titles). In most events the athletes competed naked (probably because of the heat). Several times in his odes for victors from Aegina Pindar praises the trainer. Generally, he concentrates on the implications of victory rather than the winning itself, but occasionally he provides interesting athletics details.

In winning at the Olympics both the stadion race and the pentathlon Xenophon of Corinth achieved, according to Pindar, what had never been done before (Olympian 13.29-33). In Pythian 5 (lines 49-51) Pindar says that the charioteer of the victor, the king of Cyrene, was in a race in which forty charioteers fell. The dangers inherent in the equestrian events meant that the mean who entered those events, and who were crowned victors, did not themselves usually ride or drive but employed jockeys and charioteers; but in Isthmian 1 for a chariot-race victor, Pindar says that the winner, Herodotus of Thebes, held the reins himself (line 15), as if this was exceptional. In Isthmian 4, for a Theban pancratiast, Pindar rather surprisingly says that the victor was of puny appearance (line 50) – perhaps a joke for a fellow Theban, The ordering of the odes, Olympian, Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian, reflects the order of the games in terms of their importance; within each group of odes those celebrating victories in the chariot race generally come first because it was the event held in great esteem. No Olympian or Pythian odes is for a victor in the pancration, whereas three Nemeans and Isthmians are; conversely, eleven Olympians and Pythians, but only give Nemeans and Isthmians are for chariot – and horse-race victors. At the major games Pindar focused on the major events.

The Greek poet Pindar (c. 518-428 BC) composed victory odes for winners in the ancient Games, including the Olympics. He celebrated the victories of athletes competing in foot races, horse races, boxing, wrestling, all-in fighting and the pentathlon, and his Odes are fascinating not only for their poetic qualities, but for what they tell us about the Games. Pindar praises the victor by comparing him to mythical heroes and the gods, but also reminds the athlete of his human limitations. The Odes contain versions of some of the best known Greek myths, such as Jason and the Argonauts, and Perseus and Medusa, and are a valuable source for insights on Greek religion and ethics. Pindar’s startling use of language, including striking metaphors, bold syntax, and enigmatic expressions, makes reading his poetry a uniquely rewarding experience.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] BC, and lost in the finals of his seventh consecutive competition. He won even more titles at the other important athletic festivals of his time — the Python games, also held every four years, the Nemea and Isthmian games that […]