By Maurice E. Stucke

Wow! That is what my university’s former football coach wanted to hear from prospective student-athletes when touring the new $45 million football practice facility. Parts of my university need repair. Departments face resource constraints. But the new practice facility was to set the standard in the university’s fierce competition for talented recruits. So our former coach led reporters through the planned 145,000 square-foot building, with its grand team meeting room, custom-designed chairs, hydro-therapy room, restaurant, nutrition bar, and lockers equipped to charge iPads and cellphones. But as the tour concluded, our coach observed that several rival universities, upon seeing our planned facility, were planning even more expensive training facilities. As our rivals spend millions on elaborate facilities, none of the universities have a sustained competitive advantage. And other student needs remain unmet.

Competition is ordinarily viewed as good. It is, after all, the backbone of most developed countries’ economic policies. Promoting competition is broadly accepted as the best available tool for promoting economic well-being. Competition can yield lower prices, better quality, more choices, innovation, greater efficiency, increased productivity, and additional economic development and growth. Competition has its social and moral virtues, such as promoting individual initiative, liberty, and free association. Not surprisingly, competition can take a religious quality, especially among antitrust enforcers. They regularly try to protect the public from harmful special interest legislation, premised on complaints of excess competition.

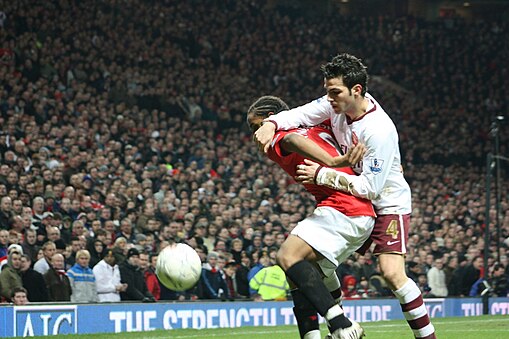

Competition, although seen as good, is not pervasive. At times the laws and informal norms stress cooperation, rather than competition. We don’t want parishioners, after all, competing for pews, or children competing for their parents’ affection. Some areas aren’t subject to market competition (e.g. human organs) or are exempt from competition laws (e.g. labor). Even though competition is generally seen as good, not all forms of competition are necessarily good. So we distinguish between fair and unfair means of competing — to promote the soccer player’s artful pass while punishing the scoundrel’s rough elbow. But for most commercial activity, competition on the merits is the presumed policy. It is the glue that binds our economy.

While watching my university’s football coach tour the state-of-the-art facilities, I wondered whether competition always benefits society. When does competition devolve into its pejorative synonyms: arms race and race-to-the-bottom? When is competition the problem’s cause, rather than its cure? These questions expose competition policy’s blind spot. Few within antitrust circles ask these questions. Instead, their elixir often is more, rather than less, competition.

Interestingly, an economist examined over a century ago these questions. Competition, Irving Fisher found, works to society’s benefit under two assumptions: first, when each individual can best judge what serves his interest and makes him happy; and second, when individual interests are aligned with collective interests. These two assumptions often are valid; competition, as a result, reliably delivers. But when these assumptions don’t hold, as recent developments in the economic and psychology literature show, competition can worsen the problem. One scenario is where firms effectively compete to exploit overconfident consumers with imperfect willpower (think credit cards). Rather than compete to help consumers obtain or find solutions for their imperfect willpower, firms instead compete in devising better ways to exploit consumers.

A second scenario is where individual and group interests diverge. Competition benefits society when individual and group interests and incentives are aligned (or at least don’t conflict). But when individual interests diverge from collective interests, as in the case of testosterone, the competitors and society are worse off. Wall Street traders, the press reports, are boosting their testosterone levels. One study found that traders, with higher morning testosterone levels, were likelier to earn more profits that day. Higher testosterone levels can increase the traders’ appetite for risk and fearlessness. So traders, weighing the benefits and risks, can rationally decide to boost their testosterone levels to gain a relative competitive advantage (or at least not be competitively disadvantaged against higher testosterone traders). However, as other traders inject testosterone, the traders no longer enjoy a relative competitive advantage. They and society are collectively worse off.

We saw this race-to-the-bottom before the economic crisis. With the expansion of Fitch Ratings, the competitive pressures on the two entrenched ratings agencies increased. Their cultures changed. They increasingly emphasized greater market share and short-term profits. To gain a relative advantage, they lowered their rating requirements. Their ratings quality deteriorated. As the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission found, Moody’s alone rated nearly 45,000 mortgage-related securities as AAA. In contrast, in early 2010, only six private-sector companies were rated AAA. So too nations compete for a relative advantage by relaxing their banking, environmental, safety, and labor protections. Their competitive race-to-the-bottom ultimately leaves them and their citizens collectively worse off.

So is competition in a market economy always good? If the answer is no, a separate issue is whether we should allow private parties to deal with these types of failures or whether legislation is required. Once we recognize that market competition produces at times worse results, the debate shifts to whether the problem of suboptimal competition can be better resolved privately (by perhaps relaxing antitrust scrutiny to private restraints) or with additional governmental regulations (which raises issues over the form of regulation and who should regulate).

So when you hear the policymaker’s refrain of making markets more competitive, competition likely is the solution. But as football coaches, Wall Street traders, ratings agencies, and nations realize, increasing competition at times worsens, rather than cures, the problem.

When he joined the University of Tennessee in 2007, Prof. Maurice E. Stucke brought 13 years of litigation experience as an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and Sullivan & Cromwell. A Fulbright Scholar in 2010-2011 in the People’s Republic of China, he serves as a Senior Fellow at the American Antitrust Institute, on the boards of the Academic Society for Competition Law and the Institute for Consumer Antitrust Studies, and as one of the United States’ non-governmental advisors to the International Competition Network. His scholarship has been cited by the U.S. courts, the OECD, competition agencies, and policymakers. You can read his article “Is competition always good?” in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement.

The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement is a new launch journal from Oxford University Press in 2013. All content is freely available online for a limited time and papers published ahead of the first print volume (April 2013) are available online now. The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement provides a platform for leading scholarship on public and private competition law enforcement, at both domestic and international levels. The journal covers a wide range of enforcement related topics, including: public and private competition law enforcement, cooperation between competition agencies, the promotion of worldwide competition law enforcement, optimal design of enforcement policies, performance measurement, empirical analysis of enforcement policies, combination of functions in the competition agency mandate, and competition agency governance. Other topics include the role of the judiciary in competition enforcement, leniency, cartel prosecution, effective merger enforcement, competition enforcement and human rights, and the regulation of sectors.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) The University of Tennessee Pride of the Southland Marching Band performs pregame at the UT vs. California football game. Photo by Jordan3757, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) Arsenal’s Cesc Fàbregas (white shirt) duels with Anderson of Manchester United. Photo by Gordon Flood, Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

[…] MAURICE STUCKE: Is Competition Always Good? […]

It seems you have concisely defined the government’s best role in fostering competition. Along Fisher’s first point, government must provide sufficient information to maximize rationality of choice. To the second, government must punish abuse between participants. Which also applies to the first point, in the sense of protecting from corporate abuse. I believe capitalist societies have evolved to do these things since Fisher’s time anyway. But you have nicely codified it.

Lamenting about the money appearing to avoid areas that other students “need”

Since we do not know the revenue stream created by the football program we do not know if the program spends more than it takes in.

How long can you reasonably depreciate the infrastructure costs, equip costs, etc… Loads of data points are missing to make a real assessment. That said, this article is perfectly ambiguous/ no “lying” but clearly slanted against the horrors of competition. That’s about the expensive stadium.

Are testosterone laced traders ruining our country? Is their risk taking a huge problem? I am so glad you chose to examine what they are trading.

They are trading cloud money and they get bailed out. Risk rewarded.

If their bosses had actual real currency/commodities on the line, the blustery boys would be reigned in.

Your infantile proposition is irrelevant.

Competition is nothing more than the ability to make comparisons. Comparisons are necessary whenever a choice or decision must be made. In sports, decisions are made by the score, but in life decisions are made by other people. It is obviously false (though a common mistake) to think that cooperation is the opposite of competition. Competition, that is, a choice of partners and roles, is necessary before cooperation is possible. The opposite of competition is no choices, no decisions and therefore, no comparisons.

Municipalities SHOULD have to compete against each other for investment dollars. It is entirely rational to dial back one’s environmental protections or safety regulations if they are so burdensome that they deter investment, and it is entirely possible that the benefits of the resultant cash infusion outweigh the costs (real or imaginary) in terms of environmental welfare or safety. Not every scenic overlook needs a guardrail. Governments are exactly as evil and rapacious as they are allowed to be.

[…] Is it always good? […]

Is competition always good seems to be the wrong question. The better question would seem to be is competition better than legislation at deciding complex economic issues, and I would answer yes, yes it is. I would always prefer the invisible hand to managed societies.

Just because competition doesn’t yield the result you prefer doesn’t mean there is anything inherently wrong with competition. You may not like the fact that many people will more willingly spend money on entertainment than higher education, but that certainly doesn’t imply the problem is with competition. And with the returns on higher education these days, can you be so certain it really is a better investment?

Competition is an effect, not a causal primary. Specifically, it is an effect of freedom. So the real question should be: “Is freedom always good?” My answer is an unqualified yes, but the answer of many pundits seems to be, “only if it results in a social outcome that I feel is desirable.”

Prof. Stucke also confuses competition with regulation. The two are not the same. Competition belongs to the marketplace. Regulation is an instrument of government. The problem is when politicians decide they must spend taxpayer money to affect the terms of the marketplace. There you get corruption.

In his opening example, the football stadium was not paid for by tuition, it was paid for by tuition that has ballooned through government-financed debt and increasing contributions from the state. Government contributions create an inflation spiral because it encourages the marketplace to charge more for its services, knowing that taxpayers will foot the bill and increase its budget the next year.

We see this every year at budget time. Noises are made about flatlining the state’s bribe to the university system, university system threatens to raise tuition, media runs articles about incoming students and how they’re worried about rising tuition, and usually the state flops and gives them a 4 percent increase. Universities raise tuition anyway (but not nearly as much as they pretended they would) and expand programs and build up the (insert sport here).

Free market competition = good.

Public sector “compeition” = wasting money

It’s as though you believe these state universities are NOT functions of the government. It is taxpayer dollars they are wasting.

Similarly, sports teams that convince municipalities to waste taxpayer money on impressive new venues are not an example of free markets.

A big “what if” for our time: consider possible alternative results for thousands upon thousands of individuals and families negatively impacted by the recent housing bubble if real competition in the housing industry had restrained or widely prevented unhealthy escalation of prices.

Wow. Apples, Oranges, and Bananas. Compared they cannot be.

Apples: The rating agencies are a horrible example because they are a government sanctioned oligopoly, not a competitive marketplace.

Note that competition has not been allowed to work in this case; almost every “loser” has been bailed out. From AIG and GM to individual mortgages, competition has not been allowed to perform its sorting function.

Oranges: The football example is competition at work. People are making very expensive, bad decisions. The university is losing money. If all goes well, the university will go broke as more and more students refuse to pay exorbitant tuition to a “football school”.

The results of competition are not instantaneous. Feedback loops have latency.

Bananas: Exploitation? I love this progressive cognitive dissonance. Apparently, humans are so stupid that we will buy – on credit – and eat anything we see on TV, but Hollywood movie violence and stereotypes have no affect on anything. Assuming no one is lying (credit cards interest rates are hardly a secret), there is no such thing as “exploitation”. People may make bad decisions, but they are not exploited (i.e. forced, against their will).

All that said, there are prerequisites for competition to work (primarily “no lying” and “contracts will be enforced”) and a government is really the only entity that can enforce them.

The question is framed poorly, because there are different types of competition, as “m” mentions.

Competition between private individuals or groups (such as corporations) is simply a manifestation of their economic freedom. Unless it is severely damaging to society (say, through externalities), nobody has the right to interfere with it.

[…] has published a blog post on the Oxford University Press OUPblog. Stucke’s piece is entitled, “Is Competition Always Good?” The post uses UT Athletics as a case study for a discussion of antitrust […]

[…] Is competition always good? – When does competition devolve into its pejorative synonyms: arms race and race-to-the-bottom. […]