By Maya Slater

The farce is at its height: the old clown in the armchair is surrounded by whirling figures in outlandish doctors’ costumes, welcoming him into their brotherhood with a mock initiation ceremony. He takes the Latin oath: ‘Juro’, falters. His face crumples. The audience gasps – is something wrong? But the clown is grinning now, all is well, the dancing grows frenzied, the play rushes on to its end.

Not till the next day will the audience find out what happened afterwards. They carried the clown off the stage in his chair, and rushed him home. He was coughing blood, dying. He asked for his wife, and for a priest to confess him. They failed to arrive before he died.

It happened 340 years ago, on 17 February 1673, but his magnificently ironic death is still central to the French understanding of Molière. He is their greatest comic playwright, unique in that he also directed his own plays and wrote his greatest parts for himself. Centuries later, this still gives the modern audience a frisson. In The Hypochondriac, sick with TB (he had his fatal seizure during the fourth performance), Molière himself spoke the following words:

‘Your Molière’s an impertinent fellow… If I were a doctor, I’d have my revenge… when he fell ill, I’d let him die without helping him. I’d say: “Go on, drop dead!”

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

A year later, Molière’s self-mockery has grown more explicit. The new play is The School for Wives Criticised, a short, informal sketch, ridiculing Molière’s critics in an argument about The School for Wives. Significantly, Molière didn’t defend his own play onstage. Instead, he himself played an absurd Marquis, who attacks Molière and his work: ‘I’ve just been to see it… It’s detestable.’ ‘Talk to us about its faults,’ says someone. ‘How should I know? I didn’t even bother to listen,’ replies the Marquis.

Molière’s second riposte to his critics, which again took the form of a short polemic play, The Impromptu at Versailles, was strikingly new, and still feels fresh and exciting today. We see Molière (who just this once played himself) and his troupe in rehearsal, trying desperately to get a performance together for the King and Court to see. The actors are uncooperative and annoying, which enables Molière to show himself trying to cope with them. He presents himself as unable to keep control of his unruly cast, breaking out in frustration: ‘Don’t you realise, I’m the one who carries the can…?’ When they finally start their rehearsal, Molière interrupts it to comment on The School for Wives, and to make some interesting general observations on acting. The play they are rehearsing is a conversation between two stupid courtiers. Molière again takes the part of the silly Marquis, and once more launches a comic attack on himself: ‘You’re desperate to justify Molière… don’t you think your Molière is played out [?]’ And then comes a moment unique in his work, where he takes over another actor’s part, and speaks as himself, in defence of his own art: ‘Wait a minute, You want to say all that a bit more emphatically. Listen, this is how I want it spoken…’

Of course the burning question must be: what was Molière like as an actor, and how did he perform his roles? We know he wore a heavy black moustache. We can assume that he excelled at portraying comic rage and frustration, from the number of furious outbursts he wrote for himself to perform. He put himself in ridiculous situations, hiding under the table in Tartuffe, performing a clumsy dance in The Bourgeois Gentleman, fleeing in terror dressed as a woman in M. de Pourceaugnac. But perhaps the most vivid account of his acting is found in a malicious satirical portrait written by the son of a rival actor:

‘He enters, nose to the wind, on bow legs, one shoulder thrust forward. His wig trails behind, stuffed full of bayleaves like a ham. He dangles his hands rather carelessly by his sides. His head sits on his back like a pack on a mule. He rolls his eyes. When he speaks his lines, the words are punctuated by endless hiccoughs.’

By the end, racked with TB, his performances had become less physically demanding. And performing the role which killed him that February night 350 years ago, that of the ludicrous hypochondriac, he was having to insert lines to excuse his own coughing, and played the part sitting in the red velvet chair which is still preserved as their most precious relic by the Comédie française theatre.

Maya Slater is Senior Reseach Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. She also writes fiction and reviews theatre and books. She is the editor and translator of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, and Other Plays by Molière.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

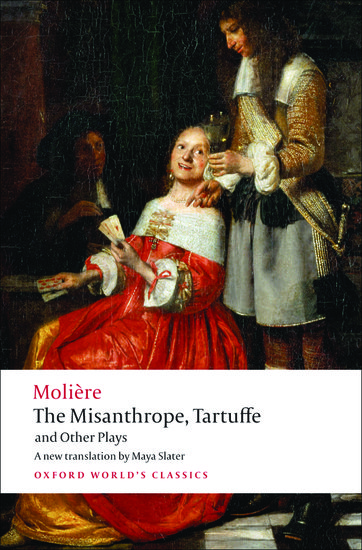

Image credit: Portrait of Molière as Julius Cesar by Nicolas Mignard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.