By Anatoly Liberman

Etymology, a subject rarely studied on our campuses, enjoys the respect of many people, even though they persist in calling it entomology. Human beings always want to know the origin of things, but sometimes etymology is made to carry double, like the horse in O. Henry’s story “The Roads We Take.” For instance, it is sometimes said that etymology helps us to use words correctly. Alas, it very seldom does so. If someone asks us about the meaning of the adjective debonair and is not only informed that a debonair man is genial, suave, and so forth but also that the adjective goes back to the French phrase de bon aire “of good disposition (nature),” this may help. But learning that the Gothic cognate of Engl. mad means “crippled” or that the historical sense of Engl. budget is “a small (leather) bag” will only confuse the speaker. Even in learning to spell etymology is rarely of service. Tuesday has ue, sleuth has eu, tube feels perfectly at ease with u, two end in wo, too is fine with oo, new has no problems with ew, unlike nu in painting, which, not unexpectedly, ends in nothing, unless you stick to French nue. And don’t forget shoe, you and ewe. The vowel in all of them is the same. A feeble explanation of each variant exists. Is a student of elementary English supposed to care? I am afraid not. (If your native language is American English, guess what The Nu Project means.) But knowing the origin of words often tells us something about the origin of things. In this respect, few examples are more trivial than lord and lady. The first of them means, from a historical point of view, “bread warden” (only one should think of loaf, rather than bread, to be able to connect the dots), while the lady of the household was a “bread kneader.” The development of both senses is instructive.

Of special interest is the meaning of divine names. Germanic myths that at one time had circulation outside Scandinavia are lost, but medieval Iceland preserved numerous tales of the pagan gods whom people venerated before their conversion to Christianity. A study of their ancient faith reveals a lost world of beliefs and superstitions. The role of etymology in the reconstruction of that world is modest but not insignificant. At the very least it can pose questions worthy of asking. For example, one of the gods was called Frey (in Icelandic, Freyr). Despite some recent attempts to disprove the common explanation, the name probably means what everybody has always thought, that is, “lord.” But in the extant myths, he is not the main figure of the pantheon. Was he such at one time? If we did not know the meaning and the origin of the word, this question would not have arisen.

In the epoch of the Vikings, everybody’s favorite was Thor (in Icelandic, Þórr), and we know for sure that Thor is a regular cognate of Engl. thunder (I’ll skip the phonetic niceties and refrain from discussing how the two forms match). Yet in the preserved corpus of Scandinavian myths Thor had nothing to do with thunder: he was a giant slayer. Luckily, etymology points the way to the past, and we begin to search for the traces of the old cult. Then we notice that Thor had a chariot (though he seldom used it), as a traveling sky god should. And he also had a hammer called Mjöllnir. This name bears a striking resemblance to the Russian word molniia “lightning.” Perhaps this resemblance is due to chance, but, more probably, not. From the nature of things a thunder god is connected with clouds and rain, and rain lets crops grow. Thunder and fertility cannot be separated. In at least two myths we are told directly that Mjöllnir was used to consecrate marriage (it was put in the lap of the bride) and possibly to guarantee the continuation of life. (Mjöllnir was not a phallic symbol, because symbols and allegories, as I think, are alien to myths; it was a substitute of Thor’s organ of procreation, and his ithyphallic figurine graces all albums of Viking art.) As long as we remember that Thor means “thunder,” all those disparate motifs fall into place.

Þórr is a comparatively rare case because we do not doubt that this name is related to the word thunder. More often the etymology of a divine name is disputable or even opaque. In the extant corpus of Scandinavian myths, the main god was Odin (Icelandic Óðinn, Old Engl. Wodan, Old High German Wuotan). He presided over war and death, as well as over magic and poetry. Next to nothing is known about his distant origin. Old Icelandic óðr means “mad,” and Modern German Wut means “fury.” When and why was Odin endowed with being furious? A mountain of articles and books has been written on the nature and descent of this god. Perhaps at one (very remote) time, he was feared and worshiped as predominantly or only a god of death, and fury constituted his main attribute. But nineteenth-century scholars detected a root in his name that they explained as “wind” and thought that in the remotest past he was not mad or furious but rather the embodiment of the storm. Some mythologists still think so, and I disagree with them respectfully but heartily.

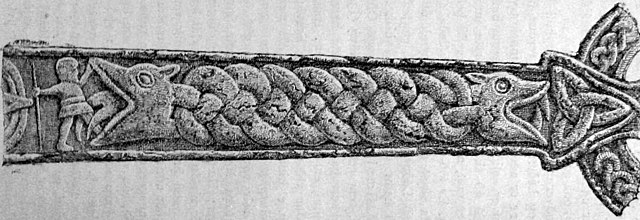

Be that as it may, a thin thread connects the modern meaning of Odin’s name and his real or putative role in people’s beliefs. Sometimes this thread is so thin as to be almost invisible. Occasionally it even seems to lead us astray. The most terrible monster of the Scandinavian mythical world was Fenrir, the wolf who in the final battle (Ragnarök) killed Odin and was torn apart by Odin’s son Vidar (Icelandic Víðarr). We may be almost certain that the root of Fenrir is fen, that is, ‘swamp.’ But wolves do not inhabit swamps! A central goddess of the pantheon (Frigg) lived in a palace called Fensalir “Fen Hall(s).” She had nothing to do with swamps either. Whence this fixation on “fens”? True, the old Germanic peoples constantly fought with swamps and suffered from the fevers that came from the pestiferous bogs of the North. Grendel, the first enemy of Beowulf, had his home in a place called mere in Old English—perhaps the sea, perhaps a forbidding marsh. Still, why did Fenrir have such a strange name, and why did Frigg live in Fensalir? Etymology does not enlighten us on this score, but once again it makes us ponder an important question.

The most pathetic figure of the Scandinavian pantheon was Odin’s son, the shining god Baldr (Engl. Balder). According to one version, he was killed by a blind god at the instigation of Loki, a suspicious character. To reconstruct the mythology of the victim and the evil counselor, that is, to present a convincing picture of how those divinities came to be and developed, it would be important to understand the meaning of their names, because once both names were as transparent as, for example, today’s Snow White and Rose Red. But the oldest functions of Balder and Loki are controversial, and the cruelest law of etymology dictates that to guess the origin of a word, we have to know the meaning of the thing. In my opinion, Loki is allied to German Loch “hole.” Odin, as I see it, was an active corpse hunter and devourer, while Loki guarded the “hole” in which the dead were interred and did not allow the dead to return to the world of the living. Bald– in Baldr seems to be akin to Engl. bald “white,” as in bald eagle (bald eagles are not “hairless”; the modern meaning of bald is the product of later development). The god of a shining sky was killed by a blind (“dark”) god of the underworld.

What I said about Odin holds for Loki and Balder. Dozens of hypotheses about the history of their names compete in the scholarly literature. Since we are not sure of what Balder and Loki did at the beginning of time, the origin of the names will of necessity remain unclear. In such matters, etymology is sometimes a good servant, but it can be a treacherous master. However, it provides the historical linguist, with a pass to Olympus and Valhalla. Patient and unflinching, an etymologist walks unobserved among the gods as their equal, even as their judge. Who else can boast of such an achievement?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Image credit: A part of the Gosforth Cross showing a humanoid figure tear apart the jaws of a monster. Usually interpreted to be Víðarr’s battle with Fenrir at Ragnarök. Signed “M Petersen” in the upper left corner. It would seem that this is the upper part of the east-facing side of the shaft of the Gosforth Cross. 1913 reproduction. Photographed from Finnur Jónsson (1913). Goðafræði Norðmanna og Íslendinga eftir heimildum. Híð íslenska bókmentafjelag, Reykjavík. Page 83. via Wikimedia Commons.

Bald eagle is first recorded by the OED in 1694, but that quotation makes it clear that bald here has the sense ‘hairless’, not ‘white’:

Philos. Trans. 1693 (Royal Soc.) 17 989 The Second is the Bald Eagle, for the Body and part of the Neck being of a dark brown, the upper part of the Neck and Head is covered with a white sort of Down, whereby it looks very bald, whence it is so named.

Indeed, the OED records no sense ‘white’ in English itself; it only refers to ‘bald’ < 'white' words in other languages, and gives the sense 'streaked with white', as in piebald.

I enjoyed this article, thank you. I would like to point out a plausible origin of Loki as Ve, via Lóðurr. Odin Vili Ve, Odin Hœnir Lóðurr, Odin Hœnir Loki. Each trio being featured in different versions of the same basic creation narrative (eg Haustlöng).