By Bill Schwarz

However Powell, as we might expect, was not one to do things by half. In the late thirties, in letters to his parents, he expressed the hope that the Tory appeasers would be strung up by the right-thinking body of stalwart Englishmen, for whom reverence for monarchy and Empire was (he believed) simply the natural order of things. In 1939, when war was declared, he relished the prospect of donning the King’s uniform and, so he hoped, dying for the King. To the end of his days, he felt robbed that he had survived the slaughter. As a young man the sole virtue he could see in marriage was that it was a social institution which enabled new generations of soldiers to be born, ready to sacrifice themselves for the Empire.

When in 1947, after decades of popular mobilization, the politicians in Westminster awakened to the fact that the British hold on the Indian subcontinent had come to an end. Independence for India was granted; the enormity of this event induced in Powell a political collapse of the first order. For him, the Empire without India was unthinkable and he had much intellectual work to do in order to imagine how England could be an entity with no Empire to rule. Through the fifties he came to conclude that the Empire had merely been a protracted historical diversion and that the reversion to an England without Empire allowed a new affiliation to the tenets of English nationhood to be re-born. Powell the English nationalist was born.

One can see why Powell is often viewed as a singular, idiosyncratic, even narcissistic figure. Few embarked on the journey he did with the same fervour and power of self-conviction. Yet the extremity of his political evolution should not blind us to the fact that many others, in many different registers, made the same journey. Powell was not alone in having to craft his persona, and his politics, to a new post-imperial reality.

But what is most striking about Powell is that, even as he arrived intellectually at the conviction that Britain’s Empire was no more and eventually came to welcome this fact, he still remained committed to the sensibilities of a hard, proconsular social vision. The system of social difference which he carried into the 1960s had clearly been forged in colonial times. On matters of race and ethnicity, class, gender and sexuality, he continued to inhabit the present as if it were still the colonial past. Through the sixties, those social forces which, as he saw things, amounted to an ‘engine for the destruction of authority’ continued to mesmerize him. And for him, supreme in this respect were the forces of blackness, which through a quirk of historical fortune had come to reside in England itself, undoing the nation and unleashing untold grief amongst its white population.

For all his narcissistic qualities, Powell was not the singular figure who was the mutant, crazed offspring of the society which nurtured him. In many respects, he came to embody its deepest unspoken fears and fantasies. And this explains, in part, the hold that Powell still exerts on English society long after his death. Powell still acts as a touchstone about race and nation. Just when you think that he has finally dispatched, back he comes. Like a traumatic memory he always returns.

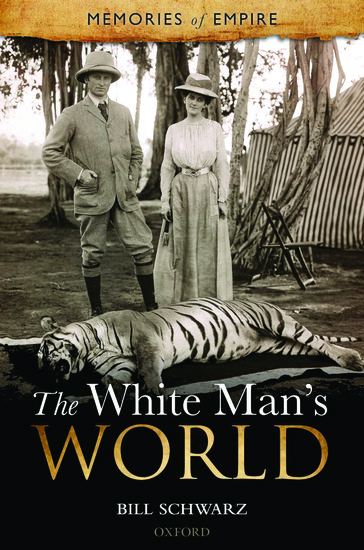

Bill Schwarz is the author of The White Man’s World and a contributor to British Cultural Studies: Geography, Nationality, and Identity. He has taught Sociology, Cultural Studies, History, Communications and English. He draws from this varied intellectual background to tell his lively story of the idea of the white man in the British empire. He has been a member of the History Workshop Journal collective for more than twenty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Enoch Powell (the story of a controversial 20th century English nationalist) […]

[…] unfolded in 1960s through to the 1980s, focussing on the central role of Enoch Powell’s ‘proconsular social vision’ in articulating a racialised vision of order and disorder that had been most clearly developed […]