By Matthew E. Gompper

As part of my recent research on the ecology of dogs and their interactions with wildlife I took the necessary first step of attempting to answer a seemingly simple question: Just how many dogs are there on the planet? Yet just because a question is simple does not mean we can confidently answer it. Previous estimates of 500-700 million dogs were rough calculations. I tried to do a bit better by pulling together hundreds of local-scale estimates and extrapolating across much larger regions. The result? One billion dogs (986,913,500 to be exact).

What are we to make of such a shockingly large number? The estimate itself is undoubtedly inexact, and in the future population demographers will likely improve on it, much as demographers studying human populations have increased the accuracy of human population size estimates. Maybe it is ten percent less than a billion. Maybe it is twenty percent more. Either way, it’s a massive number. There is something about hitting the billion threshold that makes one pause and wonder how to interpret such findings.

One way to ponder such numbers is to ask about impact. What is the impact of having a billion dogs on the planet? We tend to view dogs as benign commensals, and indeed, with only rare exceptions (such as Australian dingoes) that is the case. These billion or so dogs are entirely dependent on humans to survive. We shelter and feed them directly or indirectly ¬– the latter when dogs survive by feeding on the foods that humans have discarded. For the most part, individual dogs can’t make a living hunting wild prey. (In this sense, dogs are quite different from cats, which can survive just fine outside the bounds of human societies.)

But that doesn’t mean that dogs won’t kill the occasional prey if it has the opportunity. My dog, an Australian Shepherd that as I type is happily snoozing on the living room couch, will gladly chase any squirrel in sight even if his chance of catching it is close to nil. But ‘close to nil’ is not the same as ‘nil’, and to quote Hamlet, “ay, there’s the rub”. Occasionally, some dogs can catch the proverbial squirrel, and many dogs are better than that, regularly ranging into areas where animals are likely to be found and chasing or killing whatever they can. This ranging may be alone or with other dogs from the neighborhood; the dogs may also be accompanying their human companions. One dog doing this occasionally is not a big deal. But multiply that by a billion and we suddenly recognize the potential for dogs to be important drivers of the behavior of wildlife and important mediators of wildlife population dynamics.

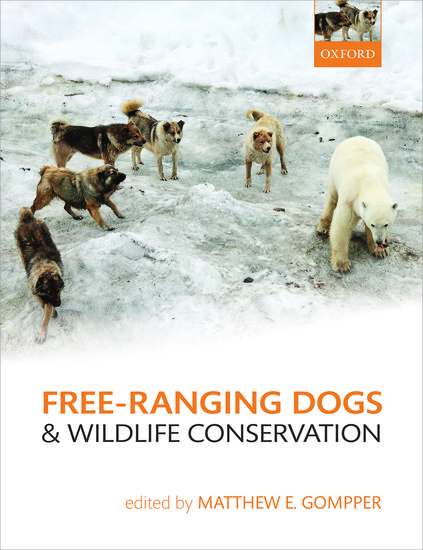

Indeed, numerous cases have been documented showing how dogs interact with and cause problems for the surrounding wildlife. Dogs disturb or kill wildlife, compete for the resources that wildlife also need, and act as reservoirs for pathogens that cause epidemics in wildlife. Dogs even act as prey for some big species of wild carnivores such as tigers, leopards, wolves and bears, and in such cases draw these species into areas where conflicts with humans are more likely. The more researchers look into the issue of dog-wildlife conflict, the more they come to recognize both the importance of the issue for protecting species and environments of conservation concern, as well as the importance of recognizing just how little we currently understand.

For instance, it would appear that a simple solution would be to restrict the ability of dogs to roam in areas where wildlife exists. Since most dogs in the developing world are fed kitchen scraps and roam in search of additional discarded food waste, combine restrictions on roaming with a better diet for dogs, and everyone wins, right? Not so fast. Commercially-produced dog foods are in many ways nutritionally similar to human foods. Producing dog food requires agricultural lands above and beyond that required for food production for people. Indeed, back of the envelope calculations based on the caloric needs of dogs suggest that the agricultural production requirements to support dogs equates to 30-40% of that required to support humans. Where would that land come from? Putting more land into agricultural development might do more damage to wildlife conservation efforts than the direct impacts dogs are currently causing.

But maintaining the status quo of allowing dogs to roam widely interacting with species of conservation concern is not satisfactory either. Nor do the norms of society allow us to cull massive numbers of dogs or confine every dog to a small space. After all, we as a global human population, like our dogs. So what are we to do? I believe a necessary first step to reducing the extent of dog-wildlife conflict may lie merely in first getting the word out regarding the importance of such issues. Once people come to realize there is an issue, locally tailored solutions, whether they involve curtailing how far dogs roam, increased oversight of dog welfare and breeding, or expanding the space set aside for wildlife, are more likely to be found acceptable than any one-size-fits-all approach to reducing dog numbers or impacts. The end result would hopefully benefit dogs, wildlife, and people.

Matthew Gompper is Professor of Mammalogy at the University of Missouri. His research examines wildlife disease ecology, the biology of mammalian carnivores (both wild and domestic), and the effects of resource subsidies on animal ecology. Gompper is the editor of Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Dry interesting article.