By Robert Fraser

I am often asked to name my favourite poem by the British writer David Gascoyne (1916-2001), my biography of whom appears with OUP this month. Bearing in mind Gascoyne was in his time an interpreter of Surrealism, an existentialist of a religious variety and a proponent of ecology, you might expect me to go for a poem along these lines. Instead, I usually choose a poem of the early 1940s entitled “Odeur de Pensée.” The title is intriguing for a start, since it translates as either “The Smell of Thought” or”‘The Scent of a Pansy.” A pansy, you will properly reply, is almost odourless; its appearance suggests fragrance without it shedding much. If it possesses a scent at all, it is so elusive as almost to be undetectable. It is thus with thought:

Thought’s odour is so pale that in the air

Nostrils inhale, it disappears like fire

Put out by water. Drifting through the coils

Of the involved and sponge-like brain it frets

The fine-veined walls of secret mental cells,

Brushing their fragile fibre as with light

Nostalgic breezes…

Hard to locate in time or place, fitting uneasily into a biographical sequence, these lines nonetheless convey so much about a writer every stage of whose existence was marked by elusiveness. To me his life seemed a patchwork of lost years, lost works, lost people. There was, for example, the saga of his pre-war diaries, compiled in Paris and London between 1936 and 1940. Gascoyne had lent them to a theatrical colleague, who had forgotten to return them. For decades he assumed them to be lost then, one morning in the early 1970s, they re-appeared on his doorstep wrapped in brown paper, having surfaced among the effects of a recently deceased acquaintance. Unpacked and eventually published, they abounded in descriptions of contemporaries well — or else scarcely — known: W.H. Auden, Igor Stravinsky, André Breton, Henry Miller.

It was the obscurer names that preoccupied me. Bettina Shaw-Lawrence, for example — where was she? As a puppy-like teenager she had been a neighbour of the poet’s in the mid-nineteen thirties. She had a walk-on part in his Paris diaries, since she had gone on to study drawing with Fernand Léger and sculpture with Ossip Zadkine. I had seen a portrait of Bettina as a voluptuous twenty-something year old painted by David Kentish who, along with Lucian Freud and Johnny Craxton, formed the nucleus of the so-called East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing haphazardly run by Cedric Morris in the early war years. If she had known Kentish, there was a fair chance she knew the rest of that ramshackle bunch. Portraiture was very much part of the scene. In 1943 Freud sketched Gascoyne several times, his four wildly differing likenesses bearing witness to the poet’s changeable personality. Had Bettina drawn Gascoyne as well?

I contacted the Bridgeman Art Library who could tell me little, though they thought she might be in Italy. A circuitous trail of contacts led to her daughter, who told me she and her mother lived north of Rome in the picturesque lake-side town of Trevignano Romano. Bettina too had lost Gascoyne’s diaries, her printed copy had been borrowed and not returned. Could I acquire a replacement? I agreed on the condition we met. Thus I lured her to Richmond in Surrey where, one crowded bank holiday, we sat in a crowded pub where I endeavoured to hear her murmured reminiscences above the din of the drinkers. It was futile, so last autumn my wife Catherine and I followed her out to Italy, where she occupies a modest flat hung with her many pictures, high above cloud-capped Lake Bracciano. Over a dinner of grilled rabbit, she told us about herself. Yes, she had known Freud and Craxton. She had even enjoyed a “brief fling” with Freud, but then who had not? Had she too, I inquired, made a portrait of my subject?

Two days later, Bettina’s daughter Julia drove us up even higher to where the unspoilt town of Sutri (ancient Sutrium) nestles amid reddish tufa rocks, out of which the Romans had once carved an amphitheatre and a cavernous temple to Mithras, converted during the middle ages into a church. We visited both sites, lunched royally, then sat in an oleander-decked piazza where, amid fragrant memories and flowers, Bettina told us about her own portrait of Gascoyne. It was executed in 1944 with pen-and-ink and colour wash when he called at her parents’ home on Richmond Green after a book-foraging expedition to the Tottenham Court Road. As with so much surrounding his life, it had vanished. She had lent it to an exhibition in London, had once caught sight of it in Gascoyne’s house on the Isle of Wight. She had not heard of it since.

Partially enlightened, we flew back to London. On my computer was a message from Gascoyne’s publisher and agent, Stephen Stuart-Smith. He had been clearing Gascoyne’s home and had come across two little known portraits of the poet, one by the Polish painter and print maker Jankel Adler (1895-1949), another by somebody called Bettina Shaw-Lawrence. They were destined for the National Portrait Gallery; the second recalled early Lucian Freud. Could I shed light on either?

The rediscovered drawing by Shaw-Lawrence epitomises a place, a period, a mood. In it Gascoyne blossoms as if from a coral reef resembling that in his 1936 collage “Perseus and Andromeda,” now on permanent show in the Tate Modern. A flowering cactus disports itself before his very nose. The poet seems unaware of its tickling the pages as he peruses one of his own works. Fastidious and intent he seems, about to escape amid the coral, like a Jack-in-the-Box into its container — elusive, sleek as a thought.

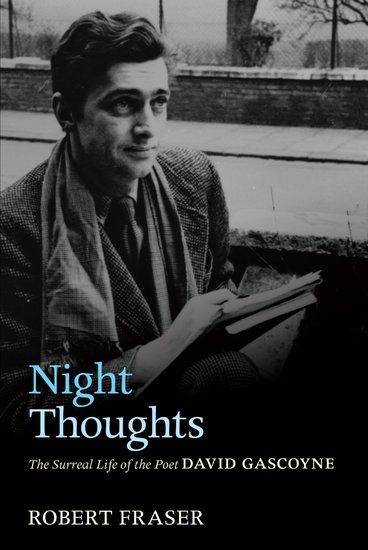

Robert Fraser is the author of books on Marcel Proust and Sir James Frazer, and of a widely reviewed biography of the poet George Barker. His latest is Night Thoughts: The Surreal Life of the Poet David Gascoyne. He has also written plays on the lives of Dr Johnson, Lord Byron, Carlo Gesualdo, Katherine Mansfield and D. H. Lawrence. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he has lectured in the universities of Leeds and London, and at Trinity College, Cambridge. Currently Professor of English in the Open University, he is a co-author of the forthcoming History of the Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

I first discovered David Gascoyne via his spellbinding 1991 review in the TLS of a major exhibition at the Tate devoted to the work of Max Ernst, a favorite artist of mine. Little did I know then that he had, as a young man over fifty years earlier, pioneered in introducing the Surrealists to the English, and known their divers lumières intimately. Several years later, I ordered his Collected Journals 1936-42, with its wonderfully atmospheric rendering of Paris as night gathered, of his own hazardous mental states, and of his numerous friendships across a dazzling galaxy of artists and poets. Later, I learned of his connection to Kathleen Raine and her own remarkable galaxy of neo-Platonists, Perennialist/Traditionalists, Blakeans and others of the “Inner Light” tendency (Schumacher, Coomaraswamy, Sherrard, Berry, Kumar, Resurgence and Temenos, &c.). The 2001 obituaries in the UK papers were stirring. I only wish more of us here in the US knew of him.

Great Book!