By James Andrew Taylor

Sometimes you can be well into writing a book before it tells you exactly what it’s about. I started work on Walking Wounded: The Life and Poetry of Vernon Scannell thinking that I was writing a simple biography of an unjustly neglected poet – which of course I was. Scannell, a serial deserter in World War II who was on the beach at D Day and seriously wounded in Normandy, had the life a biographer dreams of, full of incident and controversy – but none of that would mean anything without the poetry.

But the more I read about his life after the war – the monumental drinking binges, the black-outs, the terrifying, sweating nightmares, and most of all the raging, unreasonable jealousies and the sickening violence that he meted out to his wife and, later, his lovers – the more I began to wonder whether this was not also the story of a man seriously damaged by his wartime experiences.

A lengthy interview with Dr Felicity de Zulueta, a leading consultant psychiatrist who specialises in the treatment and effects of stress, confirmed my suspicions. No one is going to make a firm diagnosis of a man who has been dead for several years, but to her, Scannell’s life story represented a familiar account of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “It is almost a textbook example,” she said. “I certainly wouldn’t have been surprised by Scannell’s story if he had walked into my office.”

Before the war, his childhood had been a miserable combination of brutality from a bullying father and cold rejection from his mother, who stood aside as his father beat him up – another classic contributory factor leading to PTSD. It is a condition that can lead to violence, fear, sudden flashes of uncontrollable jealousy, difficulties in forming lasting relationships, and an overwhelming sense of shame. As they try to cope, sufferers often turn to drink or drugs, with disastrous results.

It sounded like a description of the man I had been writing about and getting to understand, even though Scannell, a man of his time, was predictably dismissive of such diagnoses. In one of his later poems, he mused on accounts of soldiers returning from Iraq with post traumatic stress disorder, and scoffed that, on the way to D Day sixty years before, what he had shared with the other soldiers

“Was pre-traumatic stress disorder, or

As specialists might say, we were shit-scared.”

But for all his assumed scepticism, his poetry leaves no doubt that he understood the condition and what it means to its sufferers. Gunpowder Plot tells of the terrifying memories stirred by Bonfire Night fireworks; the dramatic monologue Casualty – Mental Ward presents with chilling simplicity a wounded soldier who knows that “something has gone wrong inside my head”; A Binyon Opinion confronts the soft-focus sentimentality of “They shall not grow old” with the poet’s own more stark memories of his dead friends. And then there is Walking Wounded:

“And when heroic corpses

Turn slowly in their decorated sleep

And every ambulance has disappeared,

The walking wounded still trudge down that lane

And when recalled they must bear arms again.”

There is much more to Scannell’s poetry than the War, of course. It is the poetry of common people – his view of the Resurrection, for instance, focuses on an elderly bag-lady in canvas shoes, a sleeping drunk, and a little mongrel lifting its leg against a gravestone. When he writes poems for children, he sees the world through the child’s eyes – the corniest teenage crush, for Scannell, is as significant as the grandest of grandes passions. When he faces death – as he does, bravely – he finds himself sustained by the simplest of comforts – “Schubert and chilled Guinness”.

But, particularly as we approach Remembrance Day, it is the war poems that seem most relevant. It’s hard to think of another poet who wrote so movingly and so consistently about the plight of the victims of war who didn’t die, and who went on to live a life in which both they and those they loved were terrorised by the past. His words will resonate for hundreds of young men and women home from Iraq and Afghanistan, and for their families as well.

Combat Stress is a charity that supports some 5,400 ex-servicemen and women who are victims of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Its Communications Manager, Stephen Clark, says that many more are reluctant to come forward. “We are seeing a gradual change in society’s attitudes towards mental ill-health, but there still exists a great deal of stigma that results in many veterans suffering in silence, too ashamed to seek help,” he says.

When stories about my biography appeared online, comments reflected this lack of understanding of PTSD. “Revolting coward” is one that sticks in the memory – a harsh judgment on a man who fought in North Africa and at D Day, who saw his friend disemboweled by a shell, and who was shot in both legs.

Still, at least they demonstrate how desperately Scannell’s poetry is needed today.

James Andrew Taylor is the author of Walking Wounded: The Life and Poetry of Vernon Scannell. He has written ten other books, including biographies of the Arabian traveller Charles Doughty, and the 16th century cartographer Gerard Mercator.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

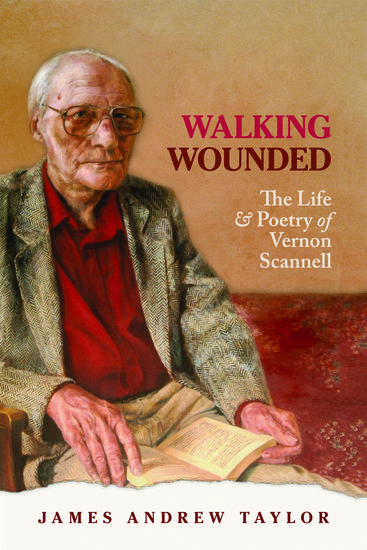

Image credit: Photograph of Vernon Scannell from Scannell family collection.

[…] Vernon Scannell portrait. Charlotte Harries/ https://blog.oup.com/2013/10/vernon-scannell-war-poetry-ptsd/ […]