By Joyce Crick

This year, Thursday December 20th is the 200th anniversary of the publication of The Grimms’ Tales for Children and the Household, currently being celebrated world-wide. Just in time for Christmas.

But even after 200 years, English-speaking countries still seem to know little more about the brothers and their stories than as a brand name for films from Disney or Terry Gilliam. How many could we name off the cuff? A dozen? Twenty?

It isn’t as if they really went away. In its two centuries of existence, their collection of stories has been selected, reprinted, translated (into 160 languages!), deconstructed, illustrated, adapted for film and theatre, rewritten and remade again and again, from the brothers’ seemingly artless transcripts of stories told them by family friends or the tailor’s widow who came selling her garden produce, all the way to Shrek.

For one thing, the collection is more various and far bigger than the core of ‘magic’ stories we label Grimms’ Fairy Tales, following the style set by their earliest translators (it started at eighty-six in the two volumes of 1812 and 1815, but grew to two hundred and ten by the seventh edition of 1857!) The presence of fables, tall tales, moralities, earthy — but not too earthy — comic anecdotes, and many literary borrowings changes the constellation we are familiar with. But it explains the brothers’ own title better.

For another, they are not strictly ‘fairy’ tales — at least, not in brother Wilhelm’s editions that followed the little book we are celebrating. There certainly were fairies at first, mainly Feen, having their origins in Perrault’s fées who did not dwell in the German countryside, but at the French court; but by the second edition of 1819 Wilhelm had banished them and any other words, like Prinzessin of such French pedigree. (He turned her into a ‘king’s daughter’.) He removed stories too: ‘Puss-in-Boots’, ‘Bluebeard’ from French sources, ‘The Hand with the Knife’ from Scottish. Why? They weren’t German enough. There is not a fairy left, not in the title and no longer in the stories themselves, though there is still enchantment of course, and plenty of wisewomen, godmothers, witches, and even a few warlocks. This points to another gap in our assumptions about the Grimms: their little book has an improbable but significant place in the much larger literary story of Romantic nationalism.

Their collection had a double purpose, ultimately contradictory. For it was also on the cusp between mere antiquarianism and the new sciences of anthropology and historical philology. This is where brother Jacob’s interests mainly lay. “To my mind the book was not written for children at all,” he wrote to Arnim. Wilhelm, though, became increasingly interested in the imaginative and educational possibilities of the collection as “a book for bringing up children.”

So even the handful of tales we do know, of lost children (more of them than just Hänsel and Gretel), strange transformations, talking animals, kings and princesses, tests and contests, rewards and fearsome punishments, journeys and homecomings, encounters in the threatening forest with wicked witches and helpful elves, were also at the beginning of a long afterlife not only in children’s imaginations but in scholarship as well. The collection turned out to hold far more possibilities than a simple publication of the tales the young men read in ancient tomes, or heard from their friends in the Hassenpflugs or the Wild girls next door or the tailor’s widow come selling her garden produce, or the curate in a neighbouring village, but rarely, it seems, direct from the mouth of the folk.

Jacob gradually left it to Wilhelm to edit the Tales to their seventh, final edition (1856-57), successively ‘enlarged and improved’ away from that first Christmas volume they had sent as a present to Arnim’s wife Bettina and their little son. Wilhelm’s ‘improvements’ between the edition we are celebrating and the last were considerable: he removed any sign of a foreign source; he added dialogue to plain narrative; combined tales; with artless art he cultivated the tales’ characteristic naive tone, turning — another contradiction — natural poesy into art poetry; his typical readership was the good bourgeois family, so he moralized, bowdlerized — though not nearly as much as his first English translators did. In other words, he made them Grimm.

So leave your laptop and join the celebrations: on December 20th choose an unfamiliar tale and read it aloud, preferably in the children’s corner of your endangered local children’s library — before the witches descend.

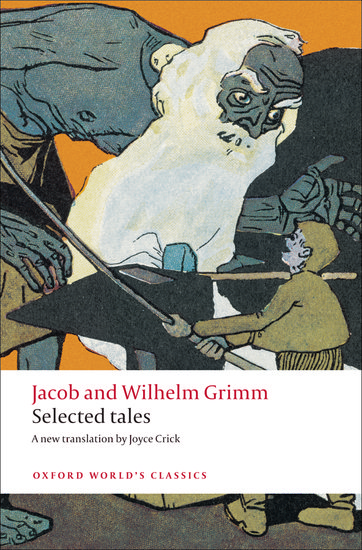

Joyce Crick taught German at University College London for many years. Since her retirement she has translated a variety of texts, including Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams for Oxford World’s Classics, which was awarded the Schlegel-Tieck prize in 2000, and Selected Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The tales gathered by the Grimm brothers are at once familiar, fantastic, homely, and frightening.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Doppelporträt der Brüder Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, 1855. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Congrats to Jacob and Wilhelm on their 200th anniversary. My their tales go on forever. Thanks for bringing up this past time. Sadly as time goes on and entertainment continues to dominate great tales such as theirs are more likely to be forgotten.

[…] celebrated the 200th anniversary of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. We loved these illustrations, National Geographic’s interactive tale […]