Coming to us through the great illustrative tradition, as well as medical and literary works, Melancholy is a perennially alluring idea. Still, the thought that a seventeenth-century work on melancholy by neither a doctor nor a philosopher could illuminate twenty-first-century concerns about mood disorders–my contention about Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy–may seem a bit far-fetched.

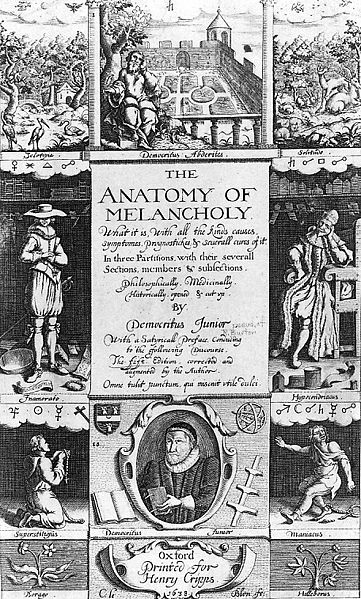

Whatever its genre (and Burton’s 1621 book has been seen as a literary work, an encyclopedia, a satire, a political tract, a health manual and much besides), and despite Burton’s identification with the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus who sought the seat of melancholy by dissecting animals, shown below by Rosa in 1650, we don’t usually assign The Anatomy of Melancholy a place alongside the great Early Modern philosophical treatises.

Notably extra-philosophical, and undoubtedly less incisively systematic or original than that by such as Hobbes, Locke, Descartes, or Spinoza, Burton’s writing is nonetheless worth our philosophical attention. By placing feelings and emotions at its heart, it avoids the ratio-centric emphasis of so much Western theorizing, for example. Addressing abnormal moods understood as disease, it begins with what can go wrong with feelings and attitudes, and why, rather than offering an account dominated by the normal case with pathology an ill-fitting afterthought. Then, wrapped in a broadly Aristotelian dualism that gracefully, if obscurely, avoids the mind-body “problem”, it is able to side-step implications of the Cartesianism that dominated psychology until almost our present century.

So, some reasons to read the Anatomy for its philosophical psychology lie in the omissions and misapprehensions we now recognize in the past writing of Early Modern and Modern times. But there is more. Those omissions and misapprehensions have had far-reaching sequelae that affect our present understanding of mood and emotion in present times, also (and this quite apart from the contested relationship between melancholy of old and today’s depression). The Modern period spawned the mind-body problem, but also psychiatry as we know it, as well as the rigid, ontologically-freighted categorical classification that gives us entities like Depressive Disorder, and the nineteenth-century conception of disease framing psychic complaints as analogous to other medical ones in every respect.

Many of these consequences in how orthodox psychiatry views mood disorder today are coming undone. Newer, critical assessments are challenging such legacies from the Modern era, leaving knowledge about affective disorder, long thought part of settled science, in growing disarray. What disordered moods are, how they come about, and their relation to social norms, as well as how to treat and respond to them – these all seem increasingly, and unsettlingly, uncertain. And particularly if there can be found congruence linking theoretical tenets and practical recommendations, as there seems to be in Burton’s Anatomy, such a context of uncertainty invites us to look again at works from past times.

Burton saw melancholy as a growing and alarming epidemic, a response to the unsettled political and religious world of his era as much as a question of imbalanced humors. And in this respect, too, the Anatomy seems a fit text for our contemporary times, where the symptoms of depression are associated with most mental disorders; “depression” is recognized as the common cold of psychological medicine (just as melancholy was in Burton’s day); and epidemiological language is increasingly employed.

At the center of these changes, recognition of the economic and social costs of mood disorders such as depression has since the beginning of the twenty-first century directed attention towards public health methods and approaches, with their emphasis on prevention. In addition, forms of cognitive therapy for depression have emerged as the main treatment alternative to psychopharmacology. To me, these trends seem a kind of real-world, present-day manifestation of the ideas Burton espoused about early prevention as the practice of a Stoic-inspired care of the soul, itself a recognizable antecedent of cognitive therapy. Paired with new ideas about the nature of mental disorders, such very Burtonian preventives and “cures” encourage a focus on the implicative connections between underlying theoretical conceptions of disorder, and these practical prescriptions. With its attention to symptoms, and to the effect of habituation brought about by repetitive, negative “melancholizing,” the picture of disease depicted by Burton resembles nothing so much as the network models of depression described (by Kendler and colleagues) today. And the connection between disease model and preventive principles found in the Anatomy offers us guidance on one way, at least, to think about issues involving depression in contemporary times.

Featured image credit: The melancholic figure of a poet leaning on an inscribed block of stone. Engraving by J. de Ribera. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.