Margot Asquith was the opinionated and irrepressible wife of Herbert Henry Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister who led Britain into war on 4 August 1914. With the airs, if not the lineage, of an aristocrat, Margot knew everyone, and spoke as if she knew everything, and with her sharp tongue and strong views could be a political asset, or a liability, almost in the same breath. Her Great War diary is by turns revealing and insightful, funny and poignant, and it offers a remarkable view of events from her vantage point in 10 Downing Street. The diary opens with Margot witnessing the scene in the House of Commons, as the political crisis over Irish Home Rule began to be eclipsed by the even greater crisis of the threat of a European war, in which Britain might become involved…

Friday 24 July 1914

The gallery was packed, Ly Londonderry and the Diehards sitting near Mrs Lowther—myself and Liberal ladies the other side of the gallery. The beautiful, incredibly silly Muriel Beckett and M. Lowther rushed round me, and others, pressing up, said ‘Good Heavens, Margot, what does this mean? How frightfully dangerous! Why, the Irish will be fighting tonight—what does it all mean?’ M. ‘It means your civil war is postponed, and you will, I think, never get it.’ I looked at these women who had been insolent to me all the session, when I added ‘If you read the papers, you’ll find we are on the verge of a European war.’

Redmond told H. that afternoon that if the Government liked to remove every soldier from Ireland, he would bet there would never be one hitch; and that both his volunteers and Carson’s would police Ireland with ease.

War! War!—everyone at dinner discussing how long the war would last. The average opinion was 3 weeks to 3 months. Violet said 4 weeks. H. said nothing, which amazed us! I said it would last a year. I went to tea with Con, and Betty Manners told me she had heard Kitchener at lunch say to Arthur Balfour he was sure it would last over a year.

Wednesday 29 July 1914

Bad news from abroad. I was lying in bed, resting, 7.30 p.m. The strain from hour to hour waiting for telegrams, late at night; standing stunned and unable to read or write; two cabinets a day; crowds through which to pass, cheering Henry wildly—all this contributed to making me tired. H. came into my room. I saw by his face that something momentous had happened. I sat up and looked at him. For once he stood still, and didn’t walk up and down the room (He never sits down when he is talking of important things.)

H. Well! We’ve sent what is called ‘the precautionary telegram’ to every office in the Empire—War, Navy, Post Office, etc., to be ready for war. This is what the Committee of Defence have been discussing and settling for the last two years. It has never been done before, and I am very curious to see what effect it will have. All these wires were sent between 2 and 2.30 marvellously quick. (I never saw Henry so keen outwardly—his face looked quite small and handsome. He sat on the foot of my bed.)

M. (passionately moved, I sat up, and felt 10 feet high.) How thrilling! Oh! Tell me, aren’t you excited, darling?

H. (who generally smiles with his eyebrows slightly turned, quite gravely kissed me, and said) It will be very interesting.

Margot Asquith’s Great War Diary 1914-1916 is selected and edited by Michael Brock and Eleanor Brock. Until his death in April 2014, Michael Brock was a modern historian, educationalist, and Oxford college head; he was Vice-President of Wolfson College; Director of the School of Education at Exeter University; Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford; and Warden of St George’s House, Windsor Castle; he is the author of The Great Reform Act, and co-editor, with Mark Curthoys, of the two nineteenth-century volumes in the History of the University of Oxford. With his wife, Eleanor Brock, a former schoolteacher, he edited the acclaimed OUP edition H. H. Asquith: Letters to Venetia Stanley.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

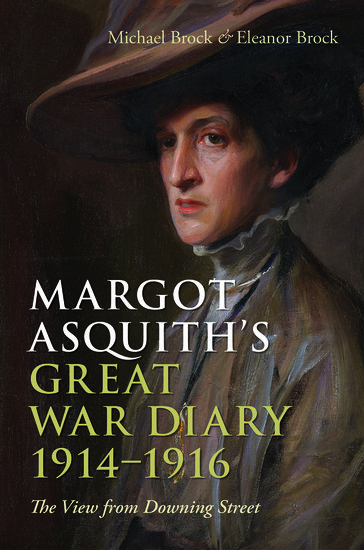

Image credit: Margot Asquith. By Philip de László. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.