By Mark Philp

Do people at the end of the eighteenth century celebrate their birthdays? More precisely, what did William Godwin (1756-1836) — philosopher, novelist, husband of feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-97) and father of Mary Shelley (1797-1851) — do on his birthday, which falls on 3 March?

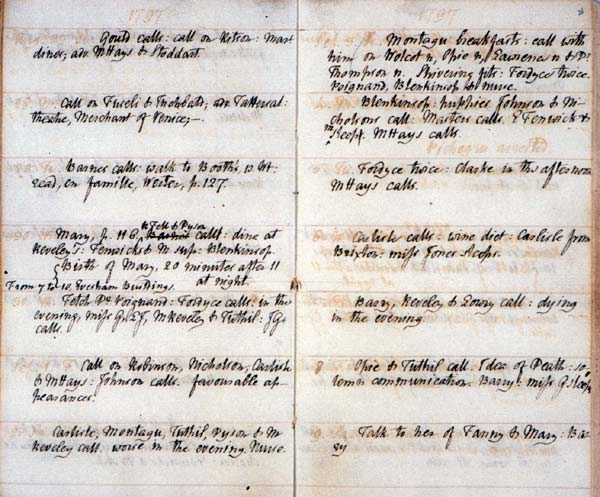

Godwin was a man of some exactitude. As a major contributor to the development of utilitarianism, the weighing of competing concerns and interests and the rigorous exercise of private judgment on the basis of rational reflection is a central theme in his philosophy. But his concern with detail is also reflected in the diary that he kept for the last 48 years of his long life. He used the diary to note things very precisely, if often cryptically — such as the entry in 1825: ‘void a large worm’; or in his twice daily recording of the interior temperature of the house for the last ten years of his life.

But he did not note birthdays. He mentions the birthday of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) in 1788 because there is a party for Gibbon hosted by the bookseller Thomas Cadell. In 1825 he mentions that of Mary Lamb, sister of the essayist Charles Lamb, when she was 61, possibly also because there was some event. The only other appearance of the phrase in the Diary is in relation to a play which he identifies as Birth Day (probably by the German dramatist Kotzebue), which he sees (in whole or part) on five occasions. Moreover, he makes nothing of his own birthday — 3 March — whether it be his 40th, 50th, 60th, or 80th. The diary entries for his birthdays are wholly undifferentiated from other days. Moreover, there is no evidence that he celebrated Mary Wollstonecraft’s birthday, nor those of any of his children.

In contrast, he noted over three hundred deaths in the diary — including ‘Execution of Louis’ on 21 January 1793, Edmund Burke on 8 July 1797, the assassination of the Prime Minister Spencer Percival on 11 May 1812, the death (also by assassination) of the German dramatist Kotzebue on 23 March 1819, but also a host of more quotidian occasions involving friends and acquaintances. Interestingly, these dates are all exact – other than Burke, who we now believe to have died the following day! But the exactitude of the others is striking because it means that Godwin was going back to his diary to fill in details as he became aware of them – the news of Louis’ execution took some 36 hours to reach Britain, and Kotzebue’s death would have travelled more slowly. This suggests that he took at least one of life’s major events very seriously, and noted the occasion with retrospective precision.

Is Godwin unusual? That he notes very occasional birthdays of others suggests both that he was, and, because he notes so few, that he was not. Or he was not unusual in the circles in which he moved — the literary and cultural circles of London in the last decades of the eighteenth and first thirty years of the nineteenth century. Moreover, he came from a family of dissenting ministers and was himself a minister in the years following his education, before turning in the 1780s to history and philosophy and an increasing agnosticism, punctuated by periods of atheism. In that tradition — nurtured on such texts as James Janeway’s, A Token for Children being an exact account of the conversion, holy and exemplary lives and joyful deaths of several young children (1671) — the manner of one’s life and death has infinitely more significance than the mere fact of birth.

This contrast is also evident in Godwin main philosophical work – Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) — is clear that there is little sacred in mere life. It is what a person does with his or her life — above all what they do for others and for the general good of the community that counts in our evaluation of them. While Godwin speculated that the lot of humanity would involve increasing subordination of the physical to the intellectual, with a concomitant shift to increasing longevity and eventual immortality, it is also clear that he took the measure of his fellow men and women in terms of how they lived their lives — hence his almost obsessive recording of the deaths of his contemporaries, both famous and obscure. The ending of life marks the point for its final reckoning. In Godwin’s philosophy that evaluation is to be made in terms of the person’s contribution to the good of one’s fellow human beings — above all, one’s contribution to their intellectual development and the expansion of the powers of mind and human knowledge. And, on that account, maybe we should commemorate Godwin’s death day instead — 7 April 1836.

Mark Philp is Professor of History and Politics at the University of Warwick. He has published widely on eighteenth century political thought and social movements and on contemporary political theory, including Reforming Ideas in Britain (2013), Thomas Paine (2007), and Political Conduct (2007). He directed the Leverhulme funded digitization and editing project on the diary of William Godwin. He co-directs the research project ‘Re-Imagining Democracy 1750-1850’ which has published Re-imagining democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, France, Britain and Ireland (2013).

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Page from William Godwin’s journal. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.