By David Roberts

It’s one of the great misunderstandings in English fiction:

It happen’d one Day about Noon going towards my Boat, I was exceedingly surpriz’d with the Print of a Man’s naked Foot on the Shore, which was very plain to be seen in the Sand: I stood like one Thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an Apparition; I listen’d, I look’d round me, I could hear nothing, nor see any Thing.

A swift retreat to the ‘castle’ follows. With sleep come the nightmares: fantasies of pursuit by ‘savages,’ dreams of the devil himself setting foot out there on the sand. The Bible provides some comfort: Wait on the Lord, and be of cheer, he reads. Then, days later, the truth dawns. It was his own footprint.

This celebrated moment in the life of the runaway, castaway sailor of York called Robinson Crusoe is the more surprising and powerful because it was written by a man who spent most of his life in — and in one way or another writing about — a sprawling metropolis. What more paradoxical subject for the lifelong Londoner, Daniel Defoe, than the horror of thinking that the island you’d thought deserted might harbour another life, or the satisfaction of knowing that it didn’t?

Defoe is often described as a realist. Ian Watt’s seminal book, The Rise of the Novel, went so far as make his ‘realism’ a pre-condition for the development of the novel. But when it came to cities, and to London in particular, Defoe was often drawn to ghosts and shadows: to dreams of emptiness as much as crowds and the great business of daily life. As Edward Hopper found the essence of New York in stray people hunched over night-time drinks amid darkened streets, so the London of Defoe’s writing often turns out to be an inversion of the place his readers knew, perhaps because he knew it better than anyone else.

Defoe is often described as a realist. Ian Watt’s seminal book, The Rise of the Novel, went so far as make his ‘realism’ a pre-condition for the development of the novel. But when it came to cities, and to London in particular, Defoe was often drawn to ghosts and shadows: to dreams of emptiness as much as crowds and the great business of daily life. As Edward Hopper found the essence of New York in stray people hunched over night-time drinks amid darkened streets, so the London of Defoe’s writing often turns out to be an inversion of the place his readers knew, perhaps because he knew it better than anyone else.

Daniel Defoe was born in the parish of St Giles, Cripplegate, the son of a butcher, and grew up listening to the preachings of Samuel Annesley, a non-conformist pastor in Bishopsgate. Schooled at Newington Green by another non-conformist, Charles Morton, he went into business in 1685, dealing in hosiery. By 1688 he was a proud liveryman of the City of London. Future ventures would take him to France and Spain, to Hertfordshire and Essex, but he always returned to London and died there in 1731.

More than any other writer, his knowledge came from the bottom up. His taste for political diatribe landed him in Newgate prison; for his defence of religious dissenters he stood in the pillory during three July days in 1703 (people stood around with flowers, forming a guard of honour). Businessman, low-church militant, and journalist, his nose for the instincts and interest of ordinary people was a shock to writers who thought literature should imitate the noble forms of classical Greece and Rome. To read his prose is to experience not the choreography of a turn round St James’s Park, but the tumbling bustle of a walk through Cheapside.

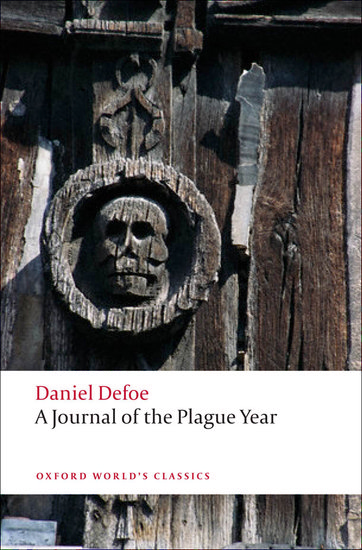

Yet his greatest tribute to his home city is not the magnificent chapter on London in A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, published in 1726, which celebrates the capital’s resources of money, trade, history and people. It is the book he had brought out four years earlier, in which he imagined what had happened when the city had been brought to the edge of oblivion during the Great Plague of 1665. A Journal of the Plague Year builds on a fascination with disaster that had gripped Defoe at least since 1708, when he published The Storm. Using old maps, mortality bills, government edicts, oral history and a host of other documents he pieced together a narrative that recreated the past in order to send out a dire warning about the future: if Londoners did not heed the threat of plague from Southern Europe, it could face extinction.

The result is an extraordinary hybrid of historical fiction and dystopian dreaming, the work of a man who could stand in the middle of a busy street and imagine himself, like Robinson Crusoe, perfectly alone.

Professor David Roberts teaches English Literature at Birmingham City University. He has taught at the universities of Bristol, Oxford, Kyoto, Osaka, and Worcester, and in 2008/09 he was the inaugural holder of the John Henry Newman Chair at Newman University College, Birmingham. He has published extensively in the fields of seventeenth and eighteenth century drama and literature, and is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. He has previously written about disaster writing for OUPblog.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Daniel Defoe. By Michael Van der Gucht (Flemish, 1660-1725) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

[…] Letters, as well as Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. He has previously written about Daniel Defore in London and about disaster writing for OUPblog. Praised in their day as a complete manual of education, and […]