The Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival 2013 is in full swing, welcoming thinkers and writers from across the globe to our wonderful city of Oxford. We’re delighted to have over thirty Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year! OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Oxford this year, you won’t miss out on all the action. Don’t forget you can also follow @oxfordlitfest and check the event schedule here.

Malcolm Gaskill will be appearing at the Oxford Literary Festival on Saturday 23rd March 2013 at 5:15 p.m. to provide a very short introduction to Witchcraft. This event is free to attend.

By Malcolm Gaskill

I’m looking at a photo of my six-year-old daughter wearing her witch costume — black taffeta and pointy hat — last Halloween. Our local vicar marked the occasion by lamenting in the parish magazine this ‘celebration of evil’. All Hallows’ Eve, the night when traditionally folk comforted souls of the dead, is not, in fact, evil, but did once have evil in its margins. Spirits on the loose might be bad as well as good, and for humans to manipulate them was witchcraft. The perception of evil, concentrated in the figure of the witch, was once powerfully real. Kate’s fancy dress character, however winsome, has a profound cultural connection to a terrifying dimension of the past and, as we’ll see, the present too.

night when traditionally folk comforted souls of the dead, is not, in fact, evil, but did once have evil in its margins. Spirits on the loose might be bad as well as good, and for humans to manipulate them was witchcraft. The perception of evil, concentrated in the figure of the witch, was once powerfully real. Kate’s fancy dress character, however winsome, has a profound cultural connection to a terrifying dimension of the past and, as we’ll see, the present too.

Myths about the ‘witch-craze’ abound. One version has it that millions of medieval women were persecuted by the church, aided by the prejudices of benighted peasants. Witchcraft accusations, we like to think, were a good way for people stupider than us to get rid of people they didn’t like or chose to scapegoat to explain misfortune in an unscientific age. This picture is essentially false. The ‘witch-hunt’ resulted in the execution of around 50,000 people (a fifth of them men), mostly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. A key development at that time was the rise of the state, with its laws and tribunals, and it was this, far more than the Catholic church, which made witch-hunting possible. Insofar as religion was involved, it was the ferocious energy unleashed by the Protestant Reformation that did most harm. Finally, if witchcraft was a pretext to bump off enemies, it wasn’t a very good one: about half of all suspicions — the few that made it into court — ended in acquittals. In England, three-quarters of all trials disappointed the accusers.

And this was no cultural dark age. These were the days of Shakespeare, Milton and Newton — no longer the Middle Ages. It was the early modern period with its new sciences and technologies, literary and artistic genius, explosions of print and commerce, global discoveries, and new ways of seeing and feeling. It’s more comfortable to think that witch-hunts preceded the Renaissance, but they didn’t, and if we look closely we ca n see why. The search for truth, and growing human confidence to find it, underpinned the inquisitorial legal process, replacing blind faith in judicial ordeals and unlimited torture. Statutes against witches and the will to use them, combined with social and economic tension caused by demographic change, largely explain the rise of witch-trials after 1500. Witches were made officially real by law and reason long before the same law and reason made them unreal by undermining the evidence on which they were tried.

n see why. The search for truth, and growing human confidence to find it, underpinned the inquisitorial legal process, replacing blind faith in judicial ordeals and unlimited torture. Statutes against witches and the will to use them, combined with social and economic tension caused by demographic change, largely explain the rise of witch-trials after 1500. Witches were made officially real by law and reason long before the same law and reason made them unreal by undermining the evidence on which they were tried.

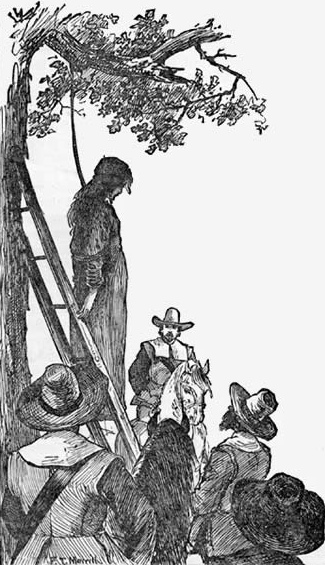

What is remarkable, even in the heyday of witchcraft prosecutions, was just how much restraint was shown in most places, at most times. There was no witch-holocaust because communities and authorities alike were preoccupied with order, and condemning innocent people did not serve that end. England had a few years during the Civil Wars when settled life was disturbed, puritan magistrates and clergy became powerful, and the normal administration of justice was interrupted. Once restraints were removed, what followed was the most savage witch-hunt in English history, with perhaps three hundred East Anglian women and men accused, and a third of them executed.

But throughout Europe and colonial north America, such events were the exceptions that proved the rule, the rule being that witch-crazes were uncommon and undesired by most. During our Halloween fun, it’s worth remembering both those who died and those who were sufficiently sceptical and fond of communal harmony to keep mass witch-hunts at bay. And we might also remember that the distance between us and such outrages is not just a few hundred years, but a few hundred miles.

On 6 February this year Kepari Leniata, a 20-year-old mother of two living in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, was accused of bewitching a six-year-old boy to death. Villagers stripped and bound her, then dragged her to a rubbish dump where she was tortured with hot irons until she confessed. The police arrived, but were held back by locals who doused Leniata in petrol and burned her alive. The UN human rights office explained that this was just the latest of numerous lynchings, each conforming to a pattern found in many parts of the developing world where witch-beliefs are strong and uncontained by law or authority.

The persecution of witches in any age says a lot about the society that allows it or cannot resist it — its structures, institutions, and social organization of power. If we in the West have successfully neutralized our most deadly fears and packaged our persecutions as harmless trick-or-treating, then perhaps we should be shouldn’t be too worried about celebrating evil. Recent events in Papua New Guinea suggest that we barely know the meaning of the word.

Malcolm Gaskill is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of East Anglia. His books include Hellish Nell: Last of Britain’s Witches (2001), Witchfinders: a Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy (2005), and Witchcraft: a Very Short Introduction (2010).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Photo provided by Malcolm Gaskill. Not to be used without express permission; the execution of Ann Hibbins on Boston Common in 1656 [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.