Flying back from Boston recently I was delighted to be able to watch the 2008 film version of Frost and Nixon. I had greatly enjoyed the play in London and heard the film was also very good. So I plugged in the headphones and settled back.

Before too long ex-president Richard Nixon is telling would-be interviewer David Frost how he bonded with his Russian counterpart Nikita Khrushchev over their shared sadnesses: Nixon had lost two brothers to tuberculosis. There it was again, the passing reference to this disease, which until the 1980s we thought the developed world had left behind.

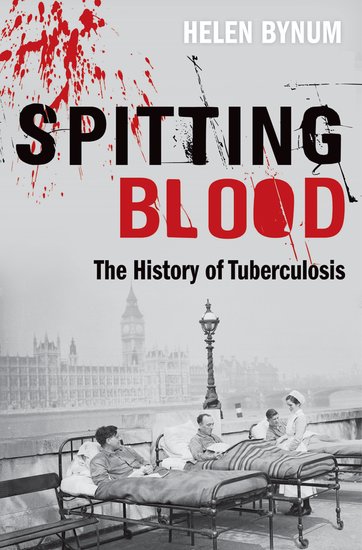

It’s been a familiar experience for me while I have been writing Spitting Blood. In completely unconnected biographies I would read about this sibling, child, parent, cousin, aunt, uncle or friend who suffered and died. When people asked me what I was working on, a common response to “a history of tuberculosis” was to tell me about who in their family or circle of close friends had died or at least had the disease. My brother-in law Louis was rendered motherless when she died on the operating table undergoing chest surgery, a final desperate measure to alleviate an otherwise gloomy prognosis. It was said in the family that she had fallen ill, dancing under the stars at a rooftop nightclub in Houston Texas, catching the “cold” that became tuberculosis. And then my respondents also often asked rather nervously, “Isn’t it coming back?”

Now before you jump in, I do know about ‘salience’ and that if I had been working on the history of a cancer or depression, the shared experiences of these diseases would have abounded, but these are very much of the here and now as well as the past. A quick Internet search will reveal lots of self-help advice for those two conditions, but not much for tuberculosis. Yet it was the switch from the past to the present, the wondering about why memories of this once common, debilitating, and deadly disease should be troubling their consciousnesses now, that seemed to unsettle.

Because yes, tuberculosis is back. Perhaps, more accurately, it never went away. In Britain, although the great epidemic of the early industrial period had long passed and the breezy sanatoria finally closed their windows and doors after the new wonder drugs of the post-WWII mopped up the final cases, there was also a residuum of illness. It lurked (and lurks) where poverty and deprivation made their homes and often overlapped with areas of intense immigration from the less well off parts of the world.

Here the disease had most certainly never gone away. It was largely ignored in the classic era of tropical medicine and empire. Then the focus was on the exotic diseases often caused by parasites and spread by insects such as malaria and sleeping sickness and the acute crowd diseases of plague and cholera. These infectious diseases could play havoc with international trade if quarantine had to be enacted. Indeed tuberculosis was thought to be a disease of civilisation that the populations of the tropics would not suffer from, still being in that innocent pre-industrial state. When people began to look for it, there was plenty of tuberculosis to be found.

After WWII, in the new era of the World Health Organisation (WHO), tuberculosis was an early priority. There were now potent antibiotics, new diagnostic technologies in the form of mass miniature X-rays, and a political will.

While the Scandinavian countries spearheaded BCG vaccination at the national level, the WHO encouraged all its member states to anti-tuberculosis programmes.

So what went wrong? What caused the recurrence of tuberculosis in the west in the 1980s and fuelled the disease’s continued devastation in middle and especially low-income countries around the world? Why are we now faced with bacteria that are resistant to the available drugs? This situation worries those leading the global fight against the disease, who fear that the gains of recent years will be lost once more.

A recent case I came across involved a friend of a friend who had happily recovered from tuberculosis; the doctors thought she had caught it while riding on the Paris Metro in the 1990s. It’s amazing how many of us have personal connections to tuberculosis today. Who do you know?

Image credit: Mycobacterium tuberculosis; in public domain, via CDC / Dr. Ray Butler.

[…] y ligeros, que se le han dedicado. A ellos ha de sumarse ahora el de Helen Bynum, que publica Oxford University Press con el acertado título de Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis. Entre los que lo han […]