By Kate Kenski

In recent years, the value of American presidential nominating conventions has been questioned. Unlike the unscripted days of old, the modern conventions are media events used to broadcast to the nation the merits of the parties’ presidential nominees as the country moves toward the general election campaign. Because of the convention scripting and pageantry akin to a hybrid of the Oscars and a rock concert, some media outlets don’t feel that the conventions are as news worthy as they once were — a view that is unfortunate. Nominating conventions are valuable events, especially in an era when candidate messages have to compete against messages from independent groups with unrestrained and seemingly unlimited funds.

Over forty years ago, political conventions were the places where party goals and policies were debated and presidential nominees were chosen. At each convention, a party could reaffirm its identity or amend its policies and priorities to reflect its adaption to historical and environmental changes affecting public opinion. Convention debates were lively, but exposure was limited primarily to those who attended the conventions. In 1972, both the Republican and Democratic parties reformed how presidential nominees were selected. The reforms were designed to create transparency to the nomination processes, which had previously been described as taking place behind closed doors in smoked-filled rooms.

The selection reforms took place amid changes in the media environment. They opened up the process to the extent that citizens, not just party elites, had some say in who became the parties’ nominees. Parties and their candidates came to the conclusion that the safest strategy for a party was to wrap up the primary process early, rather than dragging out the competition. Lengthy primary battles result in competing candidates essentially digging up and airing free opposition research for the other party. That of course means that the previous function of the nominating competitions, to select the party’s nominee, has become obsolete. While parties go through the process of counting up candidate delegates pro forma, the delegate voting is symbolic, not consequential. Media coverage of the state delegate counts is no longer prime time news material.

Reporters, editors, and producers who feel that conventions are not new and therefore are not news-worthy miss an opportunity to educate the general public about the candidates. For viewers, particularly Independents and members of the opposition party, the convention is the first meaningful exposure for a new presidential ticket. While it would be unusual for a candidate to present a completely different set of policies or ideological positions from the previous months of campaigning, the campaigns and parties use conventions to emphasize what they see as the most important issues facing the nation. It is one of the rare occasions in which the candidates get the opportunity to frame themselves and their positions unfettered by spin from their opposition and media, who seek to frame the candidates into the stories that they want to tell.

The broadcast airtime allocated to the national conventions by the networks will be thin this year, as their time allocation has been since 2000. Those interested in wider coverage of the conventions will need to turn to C-SPAN or look for segments on various cable programs. The networks, which once helped create a shared public space that emphasized the importance of politics, don’t see the benefit in continuing that public service. It is not financially profitable for them to do so.

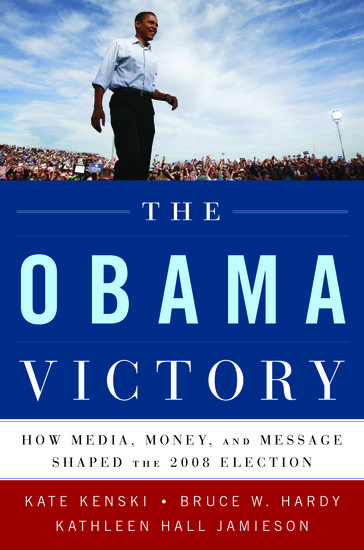

Many political scholars have overlooked the importance of conventions in swaying public opinion. While citizen predispositions and the state of the economy are the strongest factors affecting presidential vote preference, my research with Bruce W. Hardy and Kathleen Hall Jamieson shows that candidate messages matter and that convention speeches matter as a vehicle for presenting those messages. Although convention viewership is highly affected by partisan attitudes, with significant numbers of Democrats limiting themselves to Democratic convention coverage and Republicans restricting their media diet to GOP convention coverage, even taking those partisan faults into account, we have shown that political speeches move people.

During campaigns, presidential candidates not only have to worry about what their opponents say but they also have to worry about what their friends say as well. Well-meaning but ultimately misguided ideological friends often dilute the power of candidate messages by flooding the communication environment with different messages and different sets of priorities. In our post-Citizens United era, candidates need and deserve to control their basic message. Both sides of the political spectrum and hopefully those in-between should allow the candidates from the major parties to have their say, to be given a chance. If we truly believe in the ideals of our democratic republic, that citizens should be informed about where the candidates stand on issues, then providing each candidate some limited reprieve from the onslaught of attacks is warranted.

One of the biggest problems facing our nation is that we are increasingly unwilling to listen to the other side. It is difficult to hear someone utter arguments that one fundamentally disagrees with, but living in echo chambers isn’t healthy. For one moment in time, we should pay head to political conventions as an American tradition. While the format of party conventions has changed drastically over the years, their fundamental importance to the vitality of the society has not.

Kate Kenski (Ph.D. 2006, University of Pennsylvania) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication and School of Government & Public Policy at the University of Arizona where she teaches political communication, public opinion, and research methods. Prior to teaching at Arizona, she was a Senior Analyst at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. She was a member of the National Annenberg Election Survey (NAES) team in 2000, 2004, and 2008. She is co-author of award-winning book The Obama Victory: How Media, Money, and Message Shaped the 2008 Election (2010, Oxford University Press) with Bruce W. Hardy and Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Capturing Campaign Dynamics: The National Annenberg Election Survey (2004, Oxford University Press) with Daniel Romer, Paul Waldman, Christopher Adasiewicz, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson.

Oxford University Press USA is putting together a series of articles on a political topic each week for four weeks as the United States discusses the upcoming American presidential election, and Republican and Democratic National Conventions. Last week our authors tackled the issue of money and politics. This week we turn to the role of political conventions and party conferences (as they’re called in the UK). Read the previous blog posts in this series: “Romney needed to pick Ryan” by David C. Barker and Christopher Jan Carman and “The Decline and Fall of the American Political Convention” by Geoffrey Kabaservice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] in a mumbling debate with an empty chair representing President Obama. Political conventions are highly-scripted events. Eastwood’s extended, failed ad lib was anything but […]