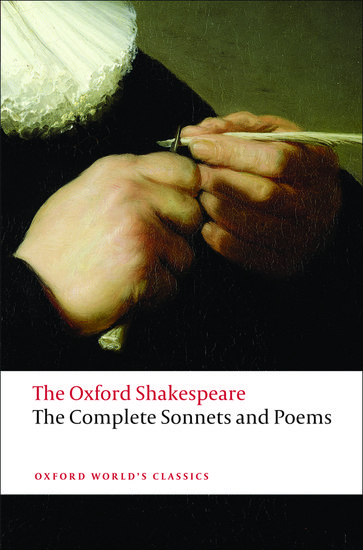

On 20 May 1609, Shakespeare’s sonnets were first published in London by Thomas Thorpe (work now found in the Folger Library). The Bard was nearing the end of his play-writing career and soon to retire. A lifetime of poetry was gathered together and printed — possibly without the permission of the author. To celebrate, we’ve excerpted Sonnet 127 and additional commentary from our Oxford World Classics edition edited by Colin Burrow — The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Sonnets and Poems. Enjoy the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s poetry.

Sonnet 127

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were it bore not beauty’s name;

But now is black beauty’s successive heir,

And beauty slandered with a bastard shame:

For since each hand hath put on Nature’s power,

Fairing the foul with Art’s false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name, no holy bower,

But is profaned, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress’ eyes are raven black,

Her brows so suited, and they mourners seem

At such who, not born fair, no beauty lack,

Sland’ring creation with a false esteem.

Yet so they mourn, becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so.

Sonnet 127 begins a group of sonnets which are chiefly about a mistress with dark hair and dark eyes whom Shakespeare never calls a ‘lady’, let alone the ‘dark lady’ favoured by his biographical critics. Scores of women with dark hair and dark eyes who were capable of doing dark deeds have been identified as her historical original (see Samuel Schoenbaum, ‘Shakespeare’s Dark Lady: A Question of Identity’ in Philip Edwards, Inga-Stina Ewbank, and G. K. Hunter, eds., Shakespeare’s Styles: Essays in Honour of Kenneth Muir (Cambridge, 1980), 221–39). Her appearance is designed to enable the sonnets to dwell on the paradoxes of finding ‘fair’ (beautiful) something which is ‘dark’. This group is likely to contain the earliest Sonnets in the sequence, for two reasons: (a) two of them appear in The Passionate Pilgrim of 1598 (138 and 144); (b) there are no late rare words in this part of the sequence. On which, see Hieatt, Hieatt, and Prescott, ‘When did Shakespeare Write Sonnets 1609?’.

1 black . . . fair Dark colouring (dark hair and dark eyes) was not considered beautiful (with a pun on fair meaning ‘blonde’).

2 Modifies the previous line: ‘or if it was called fair it wasn’t called beautiful’.

3 successive heir the true inheritor by blood. Successive is a standard term to describe hereditary succession (OED 3b) as in The Spanish Tragedy 3.1.14: ‘Your King, | By hate deprivèd of his dearest son, | The only hope of our successive line’.

4 And beauty . . . shame (a) beauty is declared illegitimate; (a) beauty is publicly shamed with having borne a bastard. The desire for paradox here creates a genealogical problem: beauty is both the source of due succession and its own illegitimate offspring.

5 put on Nature’s power usurped an office which is properly Nature’s (through cosmetics)

6 Fairing the foul making the foul beautiful (or blonde). The use of fair as a transitive verb is not common, and would have added to the deliberate strangeness here, which anticipates the witches in Macbeth 1.1.10: ‘Fair is foul, and foul is fair’.

7 no name . . . bower no legitimate hereditary title (or reputation) and no sacred inner sanctum. Bower is usually glossed as a vague poeticism (so OED cites this passage under 1b: ‘a vague poetic word for an idealized abode’), but it continues the poem’s concern with legitimate succession and bastardy, and means ‘a bed-room’ (OED 2). Not even beauty’s bedchamber is safe from profanation.

8 is profaned is defiled, perhaps with a suggestion that her holiest places have been invaded

9 Therefore because of beauty’s profanation (by the abuse of cosmetics) they are black in mourning

raven black Compare the proverb ‘As black as a raven’ (Dent R32.2).

10 brows Q’s repetition of ‘eyes’ has prompted many emendations. Staunton’s is the most convincing, since black brows (eyebrows) are elsewhere referred to by Shakespeare (L.L.L. 4.3.256–8: ‘O, if in black my lady’s brows be decked | It mourns that painting and usurping hair | Should ravish doters with a false aspect’), and are often treated as expressive (e.g. ‘I see your brows are full of discontent’, Richard II 4.1.320).

so suited and similarly attired, and. And may mean ‘As if ’, ‘as though’ (OED 3), as in Dream 1.2.77–8: ‘I will roar you an ’twere any nightingale’.

11 At . . . lack at those who, despite not being born beautiful, do not lack beauty through their use of cosmetics. Beauty here almost merits inverted commas, since it has been so thoroughly contaminated by its context.

12 Sland’ring . . . esteem giving a bad name to what is natural by making real beauty indistinguishable from false

13 so in such a way (leading to that in l.14).

becoming of gracing, suiting so well with that they become beautiful

14 so i.e. black like the mistress’s eyes

The Times Literary Supplement called The Oxford Shakespeare “not simply a better text but a new conception of Shakespeare. This is a major achievement of twentieth-century scholarship.” It offers authoritative texts from leading scholars in editions designed to interpret and illuminate the works for modern readers, including a new, modern-spelling text and on-page and facing-page commentary and notes. It was edited by Colin Burrow, University Senior Lecturer and a Fellow and Tutor of Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] It is easy to identify many reasons for this duality. The Declaration speaks in the cadences of Shakespeare and the King James Bible. By comparison, the Constitution is a mechanics manual or lawyers brief. […]