By Peter Gill

A fresh famine is threatening Africa, this time in the semi-desert Sahel region of Francophone West Africa. The greatest concern is Niger where a third of the population cannot be sure they will be able to feed themselves or even be fed over the next few months. In the region as a whole there are some ten million people at risk.

The process by which the world has learned of this crisis is familiar. The big relief agencies are allied with the broadcasters, notably the BBC, to report on the growing hunger. This publicity puts pressure on official western aid donors, governments and others, to make sure that threats of mass starvation do not turn into catastrophic reality. Relief agencies add to the pressure by reminding donors that delays to similar East African alerts last year may have contributed to upwards of 50,000 deaths in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia.

As a means of raising the profile of hunger emergencies, the media-aid agency connection has been a familiar pattern for decades. It is underpinned by increasingly sophisticated international early warning systems that monitor rainfall and cropping, and predict with accuracy the human consequences of drought and poor harvests. All but the most negligent governments in Africa take their responsibilities more seriously than they did, and mobilise local resources alongside the international efforts. The result is that the world should never again witness suffering on the scale seen in Ethiopia in the mid-1980s where 600,000 died of starvation and a new era in the aid relationship was born.

For the past quarter century, the rich North has not been allowed to forget the poor South. As western economies boomed, money flowed into the official and private aid agencies and flowed out again to the Third World. It was a movement that reached its high point in 2005 with the Gleneagles summit, Bob Geldof’s Live 8 and Make Poverty History. Yet there has been no reduction in the number of hungry people in the world; the reverse, in fact — the number has grown and major food emergencies persist.

The worst of them are those exacerbated by conflict. Fighting hampers relief and restricts the media from detailed reporting on the ground. The epicentre of last year’s East African famine was Somalia whose people have been the victims of chronic political instability for the past 20 years and where the militant Islamist group al-Shabab crudely prevented relief from reaching the starving under its control. In neighbouring Ethiopia, the worst of the suffering last year was in the border Somali region where central government faces an armed revolt — just as happened in the North of the country in the 1980s — and across the continent in Niger the current crisis is made worse by an influx of refugees from insurgencies in Nigeria and Mali.

If the world is getting better at managing the effects of extreme poverty, it is simultaneously failing to make poverty history. After more than half a century of application, the promised transformative effects of aid in the poor world have yet to be realised. Major western economies are now losing ground to new powers in the East, and with it the chance to direct the development effort in future. Western aid agencies have concentrated their efforts on health, education and welfare, yet all the new signs of African prosperity are to be found in home-grown entrepreneurship, in a growing middle class, and massive inward investment from the Chinese.

For the poorest people in the world, including those in the Sahel, there is a real danger that they will be left behind by this new-found confidence in African economies. The poor are dependent on tradition and are also its prisoners. They look to the land for their livelihoods and yet western aid agencies have over the years steadily and unaccountably reduced their commitment to agricultural development. Poor subsistence farmers must rely on what they can grow in order to feed their families and yet the number of mouths to feed continues to increase dramatically. At the beginning of the development era, aid-givers concentrated their efforts on family planning, but that priority has steadily lost ground to the belief that development itself would somehow limit population growth.

At the time of the Ethiopian famine that so shocked the world in the 1980s, the country’s population stood at some 40 million. Since then, a new government has applied itself diligently to bearing down on rural poverty and has closely followed the development prescriptions of the aid-givers. Population growth has not been the major priority that it should have been, and the consequence is that in 25 years the population doubled to 80 million. Ethiopia can point to impressive economic growth in recent years, but for the rural poor the effect of more mouths to feed is that more people live at the margins of existence.

The figures for Niger are more astonishing and even more alarming. Thirty years ago the country’s population stood at three million. It has since quadrupled to 13 million. At current growth rates, it will continue to double every 20 years, so the projection is that by 2050 it will have increased to 56 million. This is unsustainable. It is also an unfortunate commentary on the era of development. Its legacy will have to be tackled by others.

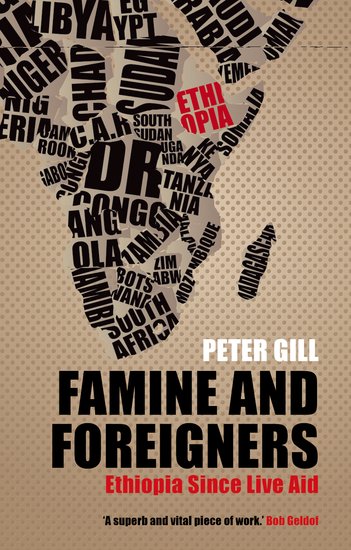

Peter Gill is the author of Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia since Live Aid, now in paperback. He has specialized in developing world affairs for most of his career, an interest that began as a VSO teacher in Sudan and his first visit to Ethiopia in the 1960s. In the 1970s he was South Asia and Middle East Correspondent for The Daily Telegraph. For TV Eye and This Week, he made films in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation, in Gaza and Lebanon, in South Africa under apartheid and in Uganda, Sudan, and Ethiopia during the famine years. He made Mr. Famine for ITV about corruption at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation and Clare’s New World about Clare Short, DFID and its first White Paper, Eliminating World Poverty. From 1999-2003, he headed the India office of the BBC World Service Trust. His first project partnered Indian broadcasters in leprosy campaigning that brought 200,000 patients forward for cure; this led to a L5 million project on HIV/Aids awareness. He has is author of Drops in the Ocean, A Year in the Death of Africa and Body Count.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.