By Robert Colls

Dear George (if I may),

Happy Birthday and best wishes on this lovely June morning. I did have a card for you but I didn’t know where to send it, so this will have to do instead. Apparently you’re a bit of a blogger yourself. Pity you’re not down here any more because you’d have plenty to blog about. Every time we hear yet more news of state surveillance and telephone tapping Big Brother is invoked. Mind you, there’s not a single telephone call in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

I hope you don’t mind me calling you ‘George’? We’ve never met and for a man of your class and generation, it might sound a bit pushy. I hope not. You’re known around the world as ‘Orwell’ but I feel I’ve known you for long enough to call you ‘George’ and to write ‘Dear Orwell’, you see, from my point of view, would seem just a little bit public school — as if we’d been to Eton together or something. So, given you don’t like your real name (Eric) and given it can’t be ‘Orwell’, it will have to be ‘George’. Sorry and all that but as you know names matter.

Anyway, I’m sending you this because I have just written a book called George Orwell: English Rebel and byway of a change I thought I’d write this in the first person as a change from all that the third person distancing which controlled our relationship over the past couple of years.

I bought my first ‘Orwell’ at Sussex University Bookshop in 1967. It was a Penguin, three shillings and sixpence, orange and black, and bought because it looked edgy. I’ve still got it — pale and crumbly, worth nothing on eBay but everything to me. The Road to Wigan Pier is a period piece now, but then I suppose we all are.

You were born 110 years ago into a different world. Your father was a lower middle-ranker in the British Raj. Your mother was a memsahib. You were another Bengal baby with a bad chest. No one ever expected you to live to 110 of course — and you didn’t. You died in 1950, age 46, at University College Hospital in Central London, alone in the night, with a massive bleeding of the lung.

Not that you feared dying. You’d been terribly ill for at least two years before hospital – losing weight, high temperatures, rattling lungs, bed, cough, blood, spit, all that — but you’d known you had TB since you were 34 and you must have suspected it long before that. As a young man you lived with tramps on the streets and in the fields and in their many and various ‘kips’. You caught pneumonia at least twice — once when you were down and out in Paris, and the other time as a young school master driving your motorbike without coat or hat from Suffolk to London in the freezing rain. After that, you got shot in Spain, bombed out in London, half drowned in Scotland and driven to the very ends of your life finishing Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Barcelona you and your first wife Eileen narrowly escaped arrest and execution while at the same time trying to save an innocent man from the very same people who were trying to arrest and execute you. This, and chain-smoking, and never enough money, and never a place to call home, and careless of everything except for the work: ‘with George, the work always comes first’, said Eileen.

You’ll be smiling ruefully at my patronizing interest in your health. But please don’t get the impression I feel sorry for you. I never feel that because you never felt sorry for yourself. But I would like to know why you took no interest. I appreciate you were not exactly one for the gym, and would have laughed at the thought of early nights and mineral water, but sometimes you seemed hell bent on self destruction. And it’s not as if you ever got tired of being alive. You enjoyed life’s pleasures, and wrote about them. You got involved in War and Revolution and wrote about that. You thrived on authority (superintendant in the Imperial Police, corporal in the Spanish Militia, sergeant in the Home Guard) but at the same time you resisted it, and distrusted it, and that became a feature of your writing too. Why were you so contrary? Some scholars revel in your ‘contradictions’. But then, some scholars never get further than ‘contradictions’.

You’ll be smiling ruefully at my patronizing interest in your health. But please don’t get the impression I feel sorry for you. I never feel that because you never felt sorry for yourself. But I would like to know why you took no interest. I appreciate you were not exactly one for the gym, and would have laughed at the thought of early nights and mineral water, but sometimes you seemed hell bent on self destruction. And it’s not as if you ever got tired of being alive. You enjoyed life’s pleasures, and wrote about them. You got involved in War and Revolution and wrote about that. You thrived on authority (superintendant in the Imperial Police, corporal in the Spanish Militia, sergeant in the Home Guard) but at the same time you resisted it, and distrusted it, and that became a feature of your writing too. Why were you so contrary? Some scholars revel in your ‘contradictions’. But then, some scholars never get further than ‘contradictions’.

As for your death, how did you deal with that? Your pal Muggeridge reckoned you knew you were a goner. He said he could see it in your face. Tosco Fyvel too said you looked stretched and ‘waxen’. Yet all the while you were sitting up and looking forward. Marrying Sonia from your hospital bed was a huge statement (but of what exactly?) and you went along with her plan to take you to Switzerland. She said she was going to be your nurse and business manager — only your body failed to live up to it. I’d like to know, incidentally, how you were going to be sick man and golden goose both at the same time.

On your 38th birthday Eileen allowed you a ‘birthday treat’, and you spent it inviting an old girlfriend to resume relations. Hmmmm. I have to ask you about that. I do have a special fondness for Eileen, you see, because like me she came from South Shields (did you ever go there?), and because she brought wit and generosity to your life. I like the sound of her. I could go on, but it would be unseemly, would it not, to tell another man how lovely his wife is? But that is what I want to do and there is a reason for it. To be straight, I think you stopped loving her but she did not stop loving you and, although it is never possible to find anything but tragedy in such situations, I am interested in the extent to which the tragedy was all hers.

No, I don’t expect you to answer that. A man who went round telling friends after her death that she was ‘a good old stick’ is not going to talk about such things.

Talking of things not said — where are your letters to Eileen? We have a number of her letters to you, and we have hundreds of letters from you to other people (about 1700 in Davison’s Complete Works), but we only have a solitary letter from you to her. What on earth happened to the rest? It’s implausible to think that that was the only one she kept and it’s equally implausible to think that any one else but you had any say in what happened to the collection. Tell me, did you destroy them because they weren’t worth keeping — or because they were?

How is it ‘up there’ by the way? My idea of heaven is that our greatest journalist goes there and tells us what it’s like. Is it a republic or a monarchy (sounds like a monarchy to me)? Is it boring (like being dead) or full of possibilities (like being alive)? And, just for the record, how was it for a godless Protestant like yourself to find you were wrong on both counts?

The big idea behind my book was to let a historian (me) have a go at someone (you) who had been well turned over by the biographers, the philosophers, the literary types, the political scientists and so on. My argument is that it was your Englishness, not your socialism, or your common sense, or your personal decency, that underpinned your writing and, after a slow start, Englishness provided you with all that a contrarian could want without having to actually surrender to one big idea. I have argued moreover that as an intellectual who was ashamed of intellectuals, Englishness provided you a persona that you might otherwise have lacked and at the same time forced you into the company of the sort of people intellectuals cant stop calling ‘ordinary’. In the end, all this battling made for a man who sought resolution in his writing…

Oh dear, this sounds far too complicated. You’ve probably stopped reading it by now. But to keep going, I have argued that for all your protestations, deep down you were a Tory. Yes, yes, I know you voted Labour and said you were a socialist and so on but I mean ‘Tory’ in the wide philosophical sense which used to include a strong sense of belonging to the people as well It’s true you followed the well worn 1930s path of middle-class men going north to gawp at working-class men. But it’s also true that, given the circumstances, you were not condescending. Rather you tried to write about them with what Edward Garnett called (in relation to D H Lawrence) a ‘hard veracity’ that matched how they worked. Am I right or wrong on this and if wrong, how wrong? And if right, how right? And if mostly right — could you please tell my reviewers?

Sorry to bother you with serious thoughts on your birthday George, but you’ve become quite a famous chap down here. To your certain horror you’ve even become slightly fashionable and it’s only a matter of time before some lithe young man calling himself ‘Orwell’ comes sashaying down the catwalk in bags and cords, thin tash and Tin Tin hair. In a certain light, TB can look like cocaine, and there’s not a day goes by that you are not quoted by some hard-pressed journalist looking for serious moral back up. Did you know they opened the XXX London Olympiad with a pageant of British history that could have been written by you? As someone who sometimes had the truth conveyed to him in dreams, maybe it was written by you? And did you know that last summer there was a move by Joan Bakewell and friends at the BBC to put a statue of you in front of Broadcasting House? Patron Saint of Journalists! Think of that! I’m not sure you’d like it. On the other hand (and one learns with you there’s always another hand) I think it’s a great idea. They say Philip Larkin’s sculptor Martin Jennings might do it. You’ll not remember Larkin. He was the weedy 19 year old who took you for a cheap meal after a talk you’d given to Oxford University English Club in 1942. Like you, he is dead but has never been more alive — and the statue helps. So come on, let’s have a statue: larger than life, scarf and coat, hands on hips, head thrust back — I have a photo of you in the book just like that.

I wonder what are you up to on your birthday? What’s the treat this time? Writing to your old girl friend again? Or a romp round the garden with Richard? Or off to the The Moon Under Water to sink a few pints with your literary mates? Now that you don’t have lungs to worry about, I can see you now scrubbing up for a night on the Celestial Town with Sonia (leaving Eileen at home knitting her brows). Who can say? Not me. I’m only the interpreter. But whatever you are doing George, I hope you are enjoying it. Here’s to you old boy, and all those who make a decent living out of you! Long may you live.

Rob

Robert Colls is Professor of Cultural History at De Montfort University, Leicester. He was born in South Shields and educated at South Shields Grammar Technical School and the universities of Sussex and York. He has held fellowships at the universities of Oxford, Yale, and Dortmund, and with the Leverhulme Trust. He is author of the acclaimed Identity of England, which is also published by Oxford University Press (2002). His new book, George Orwell: English Rebel, will be published in Autumn 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

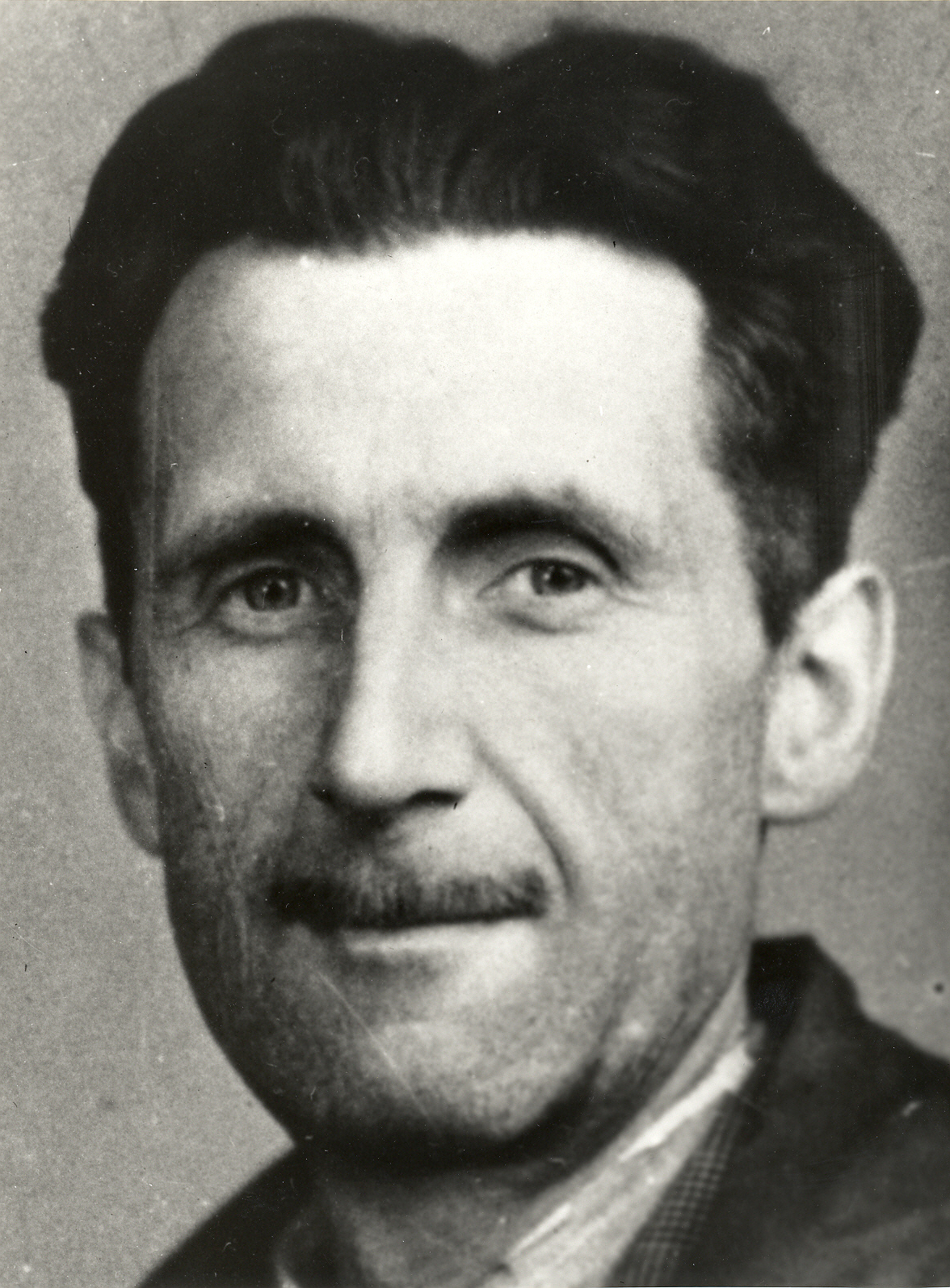

Image credit: George Orwell Press Photo. By Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ). [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

[…] omaggi. C’è chi ha scritto una lettera a George Orwell come a un Babbo Natale fuori stagione, chi ha fatto video-visita alla tomba per parlare dei […]

the reason there were no telephone calls in 1984 is there was no need as super wifi was in place like face time on iphone at all times