By Gary Kelly

A recent book on the essayist William Hazlitt calls him the ‘first modern man’. If he was, perhaps Mary Wollstonecraft was the first modern woman. By ‘modern’ I mean someone with ideas on how to cope with what sociologist Anthony Giddens calls ‘the consequences of modernity’. These include frighteningly accelerated, seemingly uncontrollable change; heightened risk of all kinds, from food supply through epidemics to weapons of mass destruction and ecological catastrophe; increased dependence on ‘abstract systems’ of unknowable complexity, from banking to government, medical science to the economy; greater migration, voluntary and involuntary, across countries and continents, classes and cultures; and, in meeting these challenges, increased dependence on ‘pure’, supposedly unselfish relationships in private and social life and on a flexible yet stable, self-reflexive and adaptable personal identity.

Wollstonecraft lived through the onset of modernity as Giddens defines it. She observed personally, analyzed incisively, and looked beyond one of modernity’s major initial crises, what many then saw as the greatest social and political cataclysm in history. She saw the blood of the guillotine on the Paris pavements and protested, at her peril. More, she understood this cataclysm from the situation of her sex, what she called ‘the wrongs of woman’, and protested, despite the peril.

Wollstonecraft certainly opposed unmodernity — the ‘Old Order’, the ancien régime — and promoted modernisation, but like her daughter Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, she understood its costs, especially to the marginalized and powerless. Among other things, Frankenstein gave powerful mythic form to a vision of modernity as human catastrophe. Wollstonecraft tried to envisage a modernity that would benefit all, from which women and other marginalized groups would not be excluded and by which they would not be victimized.

Wollstonecraft certainly opposed unmodernity — the ‘Old Order’, the ancien régime — and promoted modernisation, but like her daughter Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, she understood its costs, especially to the marginalized and powerless. Among other things, Frankenstein gave powerful mythic form to a vision of modernity as human catastrophe. Wollstonecraft tried to envisage a modernity that would benefit all, from which women and other marginalized groups would not be excluded and by which they would not be victimized.

To this end, as a self-educated, militantly independent young woman, she set out to become what she called the ‘first of a new genus’, a ‘female philosopher’. Many at the time would have derided this phrase as an oxymoron, but by it she meant a comprehensive social, cultural, and political critic, what we now call a public intellectual, representing women in particular and thereby all of the exploited and oppressed.

As a ‘female philosopher’ Wollstonecraft communicated her vision of modernity, responding to the prolonged crisis of her time, in a wide range of writing including education manuals, novels, criticism and essays, political and social polemic, historiography of the present, and political travelogue. Part of this political and cultural work required both modernizing these forms, reinventing them better to serve her vision of modernity, and inventing a new form of discourse, that of the ‘female philosopher’ rather than of the intellectual woman as some kind of ‘honorary man’. So radical was her invention, so modern, that still today many find it confused and confusing rather than ahead of its time, and perhaps ahead of ours.

Hazlitt knew Wollstonecraft’s circle of radical reformers, intellectuals, artists, writers, and publishers and what they tried to achieve. He circulated among such a circle of his own, one that included Byron, Keats, Leigh Hunt, and Percy and Mary Shelley, as well as artists and intellectuals, modernizers of all kinds, in contending interests. Hazlitt’s liberal views, increasingly celebrated in recent years, owed much to those of Wollstonecraft’s circle, with their zeal for social justice, modernization of institutions, political reform, democratic access to the arts, and concern for human value in all aspects of life, of all forms of life.

Notoriously, however, Hazlitt did not attend to Wollstonecraft’s feminism; in fact, many today see him as a misogynist. Yet I think Hazlitt’s distinctive, celebrated, and modern-seeming style, with its sharp declarations, vivid illustrations, sudden turns, personal tone and reference, lyrical passages, sarcasm and satire, owed much to Wollstonecraft’s. At the least, it was a later correlative to hers.

Wollstonecraft, much more than Hazlitt, was relegated after her death to the margins of literature and public discourse, perhaps for similar reasons; perhaps the first modern woman and man were too ‘strong’ for what became an influential Victorian and early twentieth-century consensus. Wollstonecraft was rediscovered by successive feminist movements, most recently in the 1970s; Hazlitt has received renewed attention in the past decade as a public intellectual for what Giddens calls ‘late’ modernity, and others ‘post-modernity’, our age of crisis, of ‘recession’, and ‘austerity’, and worse. In this we need all the help we can get. We could do worse than renew a conversation with the first modern woman.

Gary Kelly is Distinguished University Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies at the University of Alberta, Canada. He has edited Mary Wollstonecraft’s Mary and The Wrongs of Woman for Oxford World’s Classics, and published a book on her radically innovative style of thinking and writing, Revolutionary Feminism. He is General Editor of the ongoing multi-volume Oxford History of Popular Print Culture.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

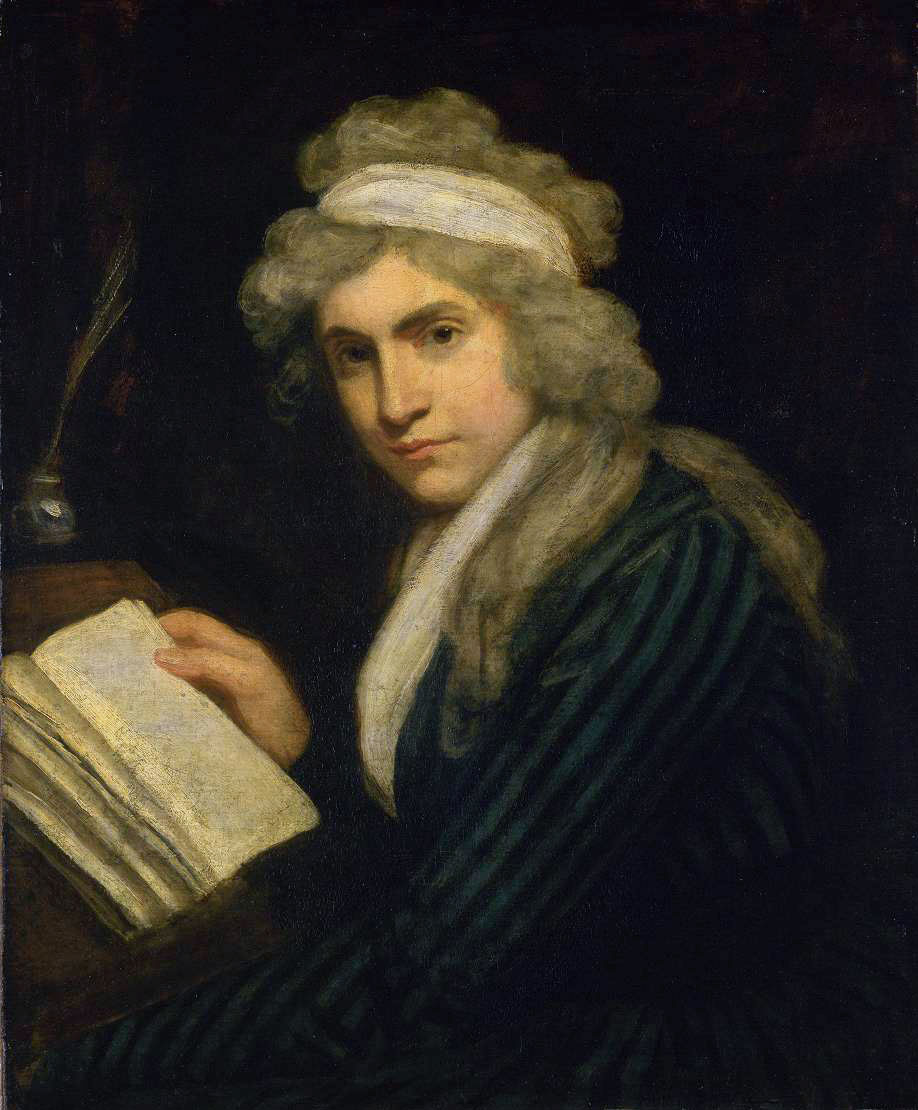

Image credit: Portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.