By Patricia Fara

Darwin and evolution go together like Newton and gravity or Morse and code. The world, he wrote, resembles ‘one great slaughter-house, one universal scene of rapacity and injustice.’ Competitive natural selection in a nutshell? Yes – but that evocative image was coined not by Charles Darwin (1809-1882), but by his grandfather Erasmus (1731-1802). Although Charles Darwin is celebrated as the founding father of evolution, his neglected ancestor was writing about evolution long before he was even born.

Erasmus Darwin’s views on evolution, politics and religion were so controversial that he was written out of history for nearly two centuries. Historians are now restoring him to his rightful place as an Enlightenment philosopher who, like Karl Marx, believed that the point is to change the world, not just interpret it. Recent research makes it clear how well-known Darwin was among his political contemporaries. A radical campaigner for equality, he condemned slavery, supported female education and opposed conventional Christian ideas on creation. Energetic and sociable, this corpulent tee-totaller was, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge put it, “the most inventive of philosophical men…He thinks in a new train on every subject.”

On top of running a successful medical practice, Darwin was a Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted industrial innovation in the Midlands, and was famous for his long poems on gardens, technology and evolution. The father of fourteen children by two wives and his son’s governess, he envisaged a cosmos fuelled by sexual energy and dominated by a perpetual struggle between the powers of good and evil. Pledging his faith in progress, he maintained that mechanical inventions would make life better for everybody and that over the millennia, a minute strand of life had evolved into insects, animals and finally people.

Modern readers (including me) can find Darwin’s poetry excruciating, but it was extremely popular at the end of the eighteenth century. His first success was The Loves of the Plants (1789), in which he personified plants as sexy mythological characters. In page after page of clunky couplets and learned footnotes, Darwin exploited the erotic connotations of botanic reproduction. Unsurprisingly, not everybody approved of his ‘blushing beauties’ frolicking with a ‘wanton air’, or his ‘hundred virgins’ flirting with their Tahitian swains amidst ‘promiscuous arrows’ shot from Cupid’s bow. But despite – or perhaps because of – the protests from scandalized reactionaries, The Loves of the Plants established Darwin as one of Britain’s leading literary figures.

As Darwin grew older, his opinions became increasingly radical. Six months after the French Revolution, he exclaimed to the engineer James Watt, “Do you not congratulate your grandchildren on the dawn of universal liberty? I feel myself becoming all French both in chemistry and politics.” His next long poem, The Economy of Vegetation (1791), was a paean to progress, strikingly illustrated by William Blake, in which Darwin hymned industrial innovation and welcomed revolutionary politics. He also castigated slavery, paying tribute to his close friend Josiah Wedgwood (Charles Darwin’s other grandfather), who invented the world’s first political icon. Some plantation owners justified their cruelty by insisting that Africans had been created separately from Europeans. In contrast, the chained slave on Wedgwood’s plaque demonstrates his intrinsic humanity by asking a question – ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

As Darwin grew older, his opinions became increasingly radical. Six months after the French Revolution, he exclaimed to the engineer James Watt, “Do you not congratulate your grandchildren on the dawn of universal liberty? I feel myself becoming all French both in chemistry and politics.” His next long poem, The Economy of Vegetation (1791), was a paean to progress, strikingly illustrated by William Blake, in which Darwin hymned industrial innovation and welcomed revolutionary politics. He also castigated slavery, paying tribute to his close friend Josiah Wedgwood (Charles Darwin’s other grandfather), who invented the world’s first political icon. Some plantation owners justified their cruelty by insisting that Africans had been created separately from Europeans. In contrast, the chained slave on Wedgwood’s plaque demonstrates his intrinsic humanity by asking a question – ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

Compassionate and caring, Darwin knew that his patients adored him, but he found it hard to cope with pain. Having watched his first wife follow her father into alcoholism, he regarded drink as poison, imposing such a strong ban that his grandson could never touch a glass of wine without feeling guilty. Witnessing the suffering of local children with measles, he questioned the Christian concept of a beneficent God, concluding that evil arises as a consequence of the struggle for existence – but good triumphs because it is associated with the health and happiness essential for survival.

In his influential medical text, Zoonomia (1794), Darwin aimed to classify animal life and hence “to unravel the theory of diseases” by dividing them into four categories. Towards its end, Darwin dared to formulate an early version of evolution, suggesting “that in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist…warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament.” Parodists fantasised about vegetables growing wings, or people rubbing off their tails by sitting in caves. Facile jokes, maybe, but this book was deemed so subversive that it was put on the Vatican’s banned list. Evolution implied that the Bible was not literally true, and – potentially more dangerous – that the working classes might improve themselves to gain positions of power.

In his most contentious poem, The Temple of Nature (1803), Darwin developed his controversial ideas still further. This manifesto for progressive evolution reveals him to be a materialist who believed in natural laws of creation. To the horror of his critics, he insisted that life stemmed originally not from some divine spark infused by God, but directly from matter. His account shocked his readers but now sounds familiar: first appearing deep in the ocean, over successive generations living organisms gradually grew larger, acquiring new forms and functions until whales governed the seas, lions the land, and eagles the air. Human beings appeared last, the culmination of continuous development, related to lowly worms and insects as well as to apes.

In public, Charles Darwin denied his grandfather’s influence, but he read Zoonomia during his short-lived spell as a medical student at Edinburgh University. A decade later, after returning from his voyage around the world, he bought a small leather-bound notebook for jotting down his nascent ideas on transformation – and at the head of the first page, he underlined his title: Zoonomia. Over twenty years after that, he eventually released On the Origin of Species (1859), his landmark account of evolution by natural selection. Can it be mere coincidence that the sub-title of his grandfather’s book on evolution was The Origin of Society?

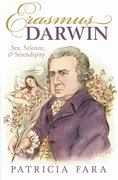

Patricia Fara is the Senior Tutor of Clare College, Cambridge, and she specializes in eighteenth-century history of science. Prize-winning author of Science: A Four Thousand Year History (Oxford University Press, 2009), her latest book is Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science and Serendipity (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Fara will be speaking at Lichfield Literature Festival and Manchester Science Festival in October 2012. For more information visit the OUP events website. You can also see Fara explaining the important of sex in her biography of Erasmus Darwin over on the OUPAcademic YouTube channel.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has granted free access for a limited time to Erasmus Darwin’s ODNB entry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Image credit: Erasmus Darwin, in public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Wedgwood Anti-Slavery Medallion. Used for the purposes of illustrating the work examined in this article. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

[…] the fullness of time, to acquiring a copy and reading it. So I was pleased when I stumbled across the article on the Oxford University Press’ blog advertising it. Pleased that is until I read the phrase out of the text used as a header for the […]

A wonderfully concise article about an amazing polymath. More can be learned at his former home in Lichfield, now open as a museum, Erasmus Darwin House.