By Martin Evans

On 5 July 1962, Algeria achieved independence from France after an eight-year-long war — one of the longest and bloodiest episodes in the whole decolonisation process. An undeclared war in the sense there was no formal beginning of hostilities, the intensity of this violence is partly explained by the fact that Algeria (invaded in 1830) was an integral part of France, but also by the presence of European settlers who in 1954, numbered one million as against the nine million Arabo-Berber population. Drawn from Italy, Malta and Spain, as well as France, these white colonials were for the most part very poor and this poverty lay at the root of their virulent racism. Feeling socially insecure, they found solace in prejudices that became the basis of a collective ‘we’ and ‘they.’ Bigotry towards the indigenous populations, whether they be Arab, Berber or Jew, peppered the daily conversation of Europeans. Even more crucially, it became the basis of a system that treated the Arabo-Berber population as second class citizens who had to be permanently shut out of colonial Algeria.

This racial inequality was the basic cause of the Algerian War, which began on 1 November 1954 when the Front de Libération National (FLN) launched a series of attacks throughout the country. The ensuing conflict produced enormous tensions that brought down four governments, ended the Fourth Republic in 1958, and mired the French Army in accusations of torture and mass summary executions. However, successive French governments could not countenance withdrawal because Algeria was seen to be the lynch-pin of the French-ruled bloc that stretched from Paris down to Brazzaville in the French Congo. Internationally this bloc — claimed by left-centre politicians like François Mitterrand and Guy Mollet — would allow France to stand up to the Soviet Union as well as British and US imperialisms.

Unable to win in Algeria, the Fourth Republic imploded in May 1958 and led to the return of the World War Two Resistance leader, Charles de Gaulle. Initially de Gaulle continued with the policy of repression and reform. Yet, by 1961 he had come to the conclusion that independence was inevitable. For him the depth of Algerian nationalism was too strong, but his decision was also a cold economic calculation. Simply speaking, Algeria was a drain of French resources. As he told a press conference on 11 April 1961 in Paris: “Algeria is costing us, this is the least one can say, much more than it brings into us.”

Thereafter the French government entered into a series of tortuous negotiations, further complicated by rebellions by dissident French army officers, who felt betrayed by de Gaulle. However, a peace agreement was brokered in March 1962 and on 1 July 1962 Algeria went to the polls with 91.5% saying ‘yes’ to independence. By this point most of the Europeans had left for France (one of the biggest population transfers of the twentieth century). On Tuesday 3 July at 10:30 a.m., de Gaulle officially recognised Algerian independence, and during the hours that followed other countries followed suit, including the USA and Great Britain. The Algerian nation state was a diplomatic reality and the Algerian Provisional Government proclaimed Thursday 5 July to be Algeria’s national Independence Day, exactly 132 years after the original French invasion.

Internationally, the end of the Algerian War was a major moment in global affairs. This significance was signalled by countless editorials across the globe marking the event, ranging from The Times and the Daily Telegraph in Britain, and The New York Times in the USA, to Il Popolo in Italy and Die Welt in West Germany. Algerian independence was history with a capital ‘H’ at the time, but it has remained so because the Algeria crisis was a pivotal event in the formal ending of European Empires.

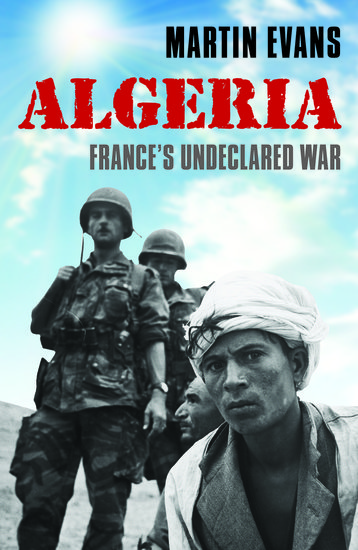

Martin Evans is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Portsmouth. He is the author of Algeria: France’s Undeclared War, Memory of Resistance: French Opposition to the Algerian War (1997), co-author (with Emmanuel Godin) of France 1815 to 2003 (2004), and co-author (with John Phillips) of Algeria: Anger of the Dispossessed (2007). In 2008 Memory of Resistance was translated into French and serialised in the Algerian press. He has written for the Independent, the Times Higher Education Supplement, BBC History Magazine and the Guardian, and is a regular contributor to History Today. In 2007-08 he was a Leverhulme Senior Research Fellow at the British Academy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

This article is so important for persons Who dont knwo the vérité of the franch colonial in algiers during 132 year of racial and torture. For exemple the franch army killed my father and trop uncles and imprimons my Mother for three year sur. …

Ali

[…] 5 July 1962: Algerian Independence […]