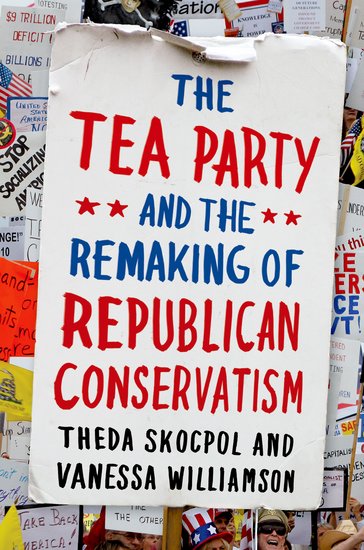

One of the great, and perhaps unexpected, emerging forces in American politics of the last decade has been the Tea Party. On February 19, 2009, CNBC commentator Rick Santelli delivered a dramatic rant against Obama administration programs to shore up the plunging housing market. Invoking the Founding Fathers and ridiculing “losers” who could not pay their mortgages, Santelli called for “Tea Party” protests. Over the next two years, conservative activists took to the streets and airways, built hundreds of local Tea Party groups, and weighed in with votes and money to help right-wing Republicans win electoral victories in 2010. In the The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, Harvard University’s Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson go beyond images of protesters in Colonial costumes to provide a nuanced portrait of the Tea Party. We asked Vanessa Williamson about her research, and what was behind both the grassroots protests and national movement.

One of the great, and perhaps unexpected, emerging forces in American politics of the last decade has been the Tea Party. On February 19, 2009, CNBC commentator Rick Santelli delivered a dramatic rant against Obama administration programs to shore up the plunging housing market. Invoking the Founding Fathers and ridiculing “losers” who could not pay their mortgages, Santelli called for “Tea Party” protests. Over the next two years, conservative activists took to the streets and airways, built hundreds of local Tea Party groups, and weighed in with votes and money to help right-wing Republicans win electoral victories in 2010. In the The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, Harvard University’s Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson go beyond images of protesters in Colonial costumes to provide a nuanced portrait of the Tea Party. We asked Vanessa Williamson about her research, and what was behind both the grassroots protests and national movement.

What did you find most surprising in your research and interaction with the Tea Party? On balance, how were you received by the people you interviewed?

When we would first reach out to local Tea Party groups, they were often quite suspicious of us, particularly because we come from Harvard University. Many we spoke to in the Tea Party believe that East Coast liberals are elitists who look down on “everyday Americans” like themselves. They also wondered, since our politics are not in line with theirs, whether we were truly interested in understanding their political activity, or whether we just wanted to attack them.

Meeting in person, however, people were extremely welcoming – which surprised us, at least at first, given how nervous people had been over email. Partly, it may be that getting to see us in person made us seem less intimidating or suspect. But also, these older, middle-class people, particularly those in the South, have very strong norms of hospitality. They frequently referred to us as their guests, and went out of their way to make us comfortable in their meeting places and homes. Only on one occasion was anyone less than polite to us at a Tea Party event – and numerous other members were clearly unhappy with the outburst, and several went out of their way to apologize privately afterwards.

How would you assess importance of the web in helping to spread and sustain the Tea Party’s messaging?

The web has played a crucial role in helping organize what would otherwise be a relatively dispersed group of older, extremely conservative people. In fact, we suspect that those in the Tea Party, particularly the older members, became more Internet-savvy as a result of their Tea Party activity! But the Internet has also allowed for the spread of ideas that are sometimes far outside the mainstream of political discourse. Some of the more conspiratorial concerns we heard (for instance, about the need to revive the gold standard, about the imminent threat of martial law, about the dangers of modernizing the electric grid) occasionally appeared on Fox News or conservative talk radio, but largely survive online.

Who the “leaders” of the Tea Party are continues to be a subject of debate. Do you expect the Tea Party ever to have a centralized organizational structure?

No. In our book, we discuss the Tea Party as the confluence of three long-standing strands of conservativism, which worked together in new ways in the first years of the Obama Administration. First, older, white, middle-class conservatives, many of whom had been previously involved in politics or local affairs, were demoralized after the electoral defeats of 2008, and looking for new leadership. Second, conservative media outlets, particularly Fox News and talk radio, helped mobilize and direct these grassroots conservatives. Third, long-standing extreme free-market advocacy groups, like Americans for Prosperity and FreedomWorks, took advantage of the new activism to build connections with grassroots conservatives and to push their agenda in Washington. These groups had similar goals in 2009 and 2010 – revitalizing conservatism, derailing the Obama Administration’s progressive agenda, and pushing the Republican Party to the right. But, as we discuss in the book, these groups do not always have the same policy goals, and in 2012, the Republican Party will have to appeal to moderates to win back the presidency. So it is unclear that the Tea Party label will continue to be a banner that these various conservative forces can rally behind.

Does the possibility exist for a split within the Republican Party?

Not because of the Tea Party. There are always factions within a party, and the Tea Party supporters make up a major component of the Republican base. To the extent they are frustrated with the Republican Party, it is because they see the party as inadequately conservative, not because the Tea Party voters are political independents.

What differences do you foresee in the role of the Tea Party in the 2012 elections versus the role they played in 2010?

First of all, Tea Party sympathizers will make up a far smaller portion of the electorate in 2012. Far fewer people vote in midterm elections, and those who do tend to be older, wealthier, and more conservative. In general elections, like 2012, we tend to see higher rates of turnout among the young and among minorities. So the influence of the Tea Party at the grassroots will be diluted. The elite aspects of the Tea Party, of course, will still be influence campaign contributors. And we are seeing the Tea Party play a role in the Republican primaries – a point we discuss in detail in our New York Times post.

Vanessa Williamson is a PhD candidate in Government and Social Policy at Harvard University and co-author of The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. Previously, she served as the Policy Director for Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

[…] But none of them can call it “unconstitutional” anymore, taking the wind out of the Tea Party‘s […]

[…] was not therefore surprised by the rise of the Tea Party movement in recent years, nor by the way in which Tea Party supporters have combined deeply irrational […]