By Philip Murphy

In November 2013, the Commonwealth was preparing for a highly controversial Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Sri Lanka, which the Canadian prime minister had already threatened to boycott on the grounds of the abysmal human rights record of the host state. In an article I published at the time, I touched on the contrast between the pre-eminent position the Queen had obtained within the Commonwealth since the 1990s, and the organization’s own lackluster performance over that period:

‘A former prime minister of New Zealand once famously described the Queen as “the bit of glue that somehow manages to hold the whole thing together”. Increasingly, however, the Commonwealth resembles a dead parrot which relies on that glue to keep it upright on its perch.’

This particular passage was not terribly well received by London’s small but devoted band of Commonwealth enthusiasts (who sometimes resemble the more orthodox members of the old Communist Party of Great Britain in seeing each apparently terminal setback for their cause merely as a chance to reaffirm their unshakable faith that it will ultimately prevail). Yet it neatly, if rather provocatively, summarized one important point. By the mid-1970s, as the Commonwealth seemed to be set on a genuinely radical trajectory – its attentions focused on the campaign against white minority rule in Southern Africa – the link with the British royal family had become something of an embarrassment. Both the Commonwealth Secretariat and the British Foreign Office were distinctly nervous about anything that might highlight this connection fearing it would offend republican susceptibilities and serve as a reminder of the organization’s imperial origins. By contrast, in recent years the link to the Queen has been actively promoted, a tacit admission that from the point of view of most of the world’s media it is now the only news-worthy aspect of the Commonwealth.

The Sri Lankan CHOGM was the public-relations disaster that many of us had predicted. The Canadian prime minister, Stephen Harper, carried out his threat to boycott the meeting. The prime minister of Mauritius, whose country was due to provide the venue of the next CHOGM, not only followed Harper’s example, but actually withdrew his offer to host the 2015 summit. Manmohan Singh, the prime minister of India, the Commonwealth’s most populous nation, also bowed to domestic pressure not to travel to Sri Lanka. Perhaps the most troubling fact for supporters of the Commonwealth, however, was that the majority of heads of government failed to attend the 2013 CHOGM, either out of principle or simply because they judged that there were better uses of their time. Even the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, who did attend the summit, made a point of travelling to the Tamil-dominated north of the island where, in front of the press, he met some of those who had suffered and lost relatives in the country’s brutal civil war. In the process, he skilfully defused some of the criticism that had been levelled at him in the UK over his decision to go to Sri Lanka. But having spent his time essentially digging himself out of the political hole that the Commonwealth had constructed for him, it seems unlikely that the experience did much to enhance his confidence in the organization. The Queen herself had neatly side-stepped the controversy, having announced earlier in the year that as part of a general review of her long-haul travel commitments she would not be flying to Sri Lanka (a perfectly plausible get-out-of-jail-free card for a woman of 87, but one that might still have seemed slightly suspicious to those familiar with her firm contention, over many decades, that it was her ‘duty’ as head of the Commonwealth to be present at CHOGMs). Instead, she sent Prince Charles as her representative, in what appears to be part of conscious strategy by the Palace to prepare the way for his ultimate succession to the headship (a role which is not formally hereditary).

In the wake of the fiasco of the Sri Lankan summit, anyone unaware of the Queen’s profound personal commitment to the organization might have expected her to avoid the subject of the Commonwealth in her 2013 Christmas Day broadcast. Instead she devoted roughly as much space to it as she did to the birth of her new great-grandson, invoking the Commonwealth’s ‘family ties’ and ‘common bond of friendship’. The rhetoric of Empire/Commonwealth as a family had been a staple of royal Christmas broadcasts since George V first began the tradition in the 1930s. Many would regard this simply as a myth designed to sanitize the grim reality of imperial domination which has survived the collapse of colonial rule. For the Queen herself, however, it remains of profound personal significance. Readers who believe that the Commonwealth still has a positive contribution to play in international affairs might well view as positively heroic her role in defending the organization, even at times of crisis. Those critical of the Commonwealth’s record and skeptical of its continuing value, and certainly those who feel that a hereditary monarch has no legitimate role to play in shaping the politics of a democracy are likely to be far less impressed. For in promoting the idea that the Commonwealth was in some sense ‘above’ politics, the Queen has indeed been an active player in post-war international affairs. And she shows no signs of intending to abandon this cherished cause.

Philip Murphy is Director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and Professor of British and Commonwealth History at the University of London. He graduated with a doctorate from the University of Oxford and taught at the Universities of Keele and Reading before taking up his current post. He has published extensively on twentieth century British and imperial history and the history of the British intelligence community. His latest book is Monarchy and the End of Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

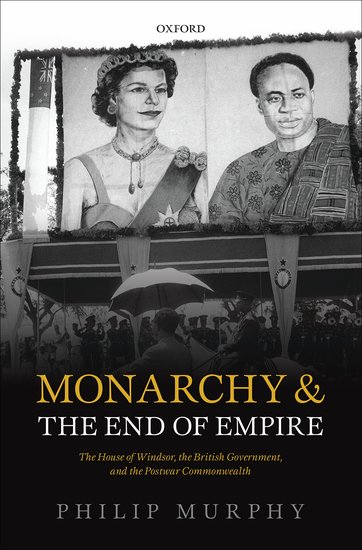

Image credit: British Prime Minister David Cameron is coming out from a shanty home in Sabapathi Pillai Welfare Centre in Chunnakam, outside Jaffna town on 15 November 2013. By UmakanthJaffna. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.