By Denis Sampson

Noli timere, Seamus Heaney texted to his wife in his last hours of life, ‘Have no fear’. It was his son who revealed this message when he spoke at the funeral service. This was a private communication, but his son must have known how much in character it was, that his father believed so much of the best in life is drained away by fear. Living fearlessly may have been a human ideal that came to him as he observed families and neighbours and a whole population living in terror for years on end during the Troubles. Fear was, perhaps, something he had to confront in himself, for even as he moved away from the battlefield in Belfast to Glanmore in the Wicklow mountains south of Dublin, the daily atrocities went on, their reverberations still echoing in his poems. Perhaps, indeed, he felt that the creative act itself, at the centre of his life, had to conquer fear, and that the imagination could not be free to create if fear overwhelmed it: ‘walk on air,’ he counseled himself, ‘against your better judgement’.

But this private message to his wife and family was not his last word as poet, for in his final collection, Human Chain, he placed at the end a poem called ‘A Kite for Aibhín’ and its last word is ‘windfall’. He recalls a moment in childhood: ‘I take my stand again, halt opposite /Anahorish Hill to scan the blue’. He is back in his birthplace with friends attempting to launch a kite. It ‘goes with the wind . . . / climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher’ until the string breaks and ‘the kite takes off, itself alone, a windfall’. Since the first collection, Death of a Naturalist, mapping the place around Anahorish, he was taking off. Concrete, physical, his language could always break free into the marvelous. The energy of the wind carried him upwards and the poems set free might land at our feet, windfalls from the blue.

I would not have considered these closing poems had I not been mesmerized by ‘Postscript’, the final lines of The Spirit Level, which he also kept as the final poem in Opened Ground: Poems 1965-1995. When I read that poem, after being an intermittent reader through the decades, I was caught off guard: this last poem, an afterthought, allowed a glimpse through the back door, as it were, into the workings of his imagination. Somehow, when I came upon this ‘windfall’ poem, I felt that it would allow me to discover all the creative energies, the registers of a voice, the themes and variations woven into a symphony, all the colours and reflections inside a major ‘monument of unaging intellect’.

It may be that I felt a personal connection to ‘Postscript’ because of its location. It was, I understand from Stepping Stones, written as a ‘postcard’ for Brian and Ann Friel who had driven along the southern shores of Galway Bay with him. The poem follows the Atlantic coast of Clare as they drive, ‘the wind / and the light are working off each other’, the ocean is wild, there is a Yeatsian lake with swans, and they might have stopped to take in the spectacular view. But this is a moment of energetic intensity culminating in ‘big soft buffetings come at the car sideways / And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’ I gasped the first time I read it, for I had often driven that road, not far from where I grew up, and then this poem of openness to the wind and the light and the literary promptings seemed to open a way into Heaney’s creative energy. The poem was less a postscript than a manifesto.

It was the larger excitement of discovery that moved me. It felt like another Heaney had come to life, one more fully alive than the dazzling wordsmith I had encountered in all my years of admiring and appreciating. Those last words felt like a beginning of a new kind of confidence and trust in the supreme poet, trust also in my ability to read him and find the life-blood of the whole endeavour: the fearless heart.

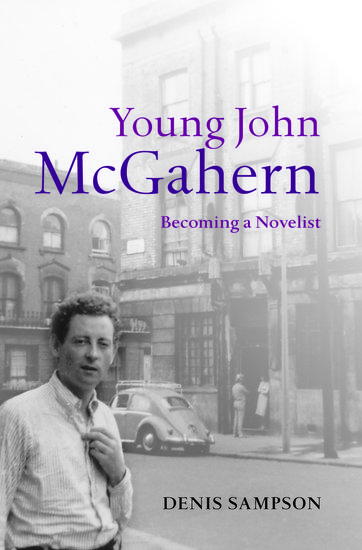

After studying literature in University College, Dublin, Denis Sampson moved to Montreal, where he earned a Ph.D. at McGill University. He has lived and worked in Montreal since the 1970s but returns to spend part of each year in Ireland. He is the author of Young John McGahern: Becoming a Novelist. He also writes personal essays (memoir and travel), book reviews, and literary features, broadcasts on the radio, and gives talks and public lectures.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Seamus Heaney. By Sean O’Connor, cropped by Sabahrat [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Just a nit:

Noli temere, Seamus Heaney texted to his wife in his last hours of life, ‘Have no fear’. It was his son revealed this message when he spoke at the funeral service.

“It was his son who revealed …” maybe?