By Thomas R. Dunlap

Bird Day began in 1894 as part of the wildlife conservation movement that sprang up in response to the slaughter of the bison and the Passenger Pigeon. Birds always had a large role, for they were threatened but also familiar and fascinating. More than any other form of life they drew and held people, becoming for many a lifelong interest, passion, and even obsession. This generation made identifying birds by sight or (less frequently) song a popular hobby, and with it a new kind of book: the field guide. Birding now draws more people than any other outdoor recreation, from every part of the country and ranging from those who want to see every bird on earth to the much greater number who keep a field guide on the windowsill and a casual eye on the bird feeder in the backyard. They buy guides of every kind and check websites with up-to-date information on migration, rarities, and oddities. Some birds become celebrities. “Pale Male,” one of a pair of red-tailed hawks nesting in New York City, attracted a local, then a national following, and their courtship and nesting led to a book, Red-tails in Love.

Birders always went with bird conservation for Audubon’s founders saw the hobby as a way to get women outdoors and interested in nature so they would support bird conservation. Their political work began with campaigns against market hunting and for the protection of songbirds, went on through work for nature reserves, then the banning of pesticides like DDT, and saving the ecosystems on which birds—and all of us–depend. Birders’ cooperation with science goes back as far and has a rich a history. In 1900 amateurs sent their observations to ornithological journals; in the 1920s they joined the national bird-banding program organized by the Bureau of Biological Survey; in the 1980s signed up for the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Breeding Bird Survey; and now they contribute to citizen science programs gathering data to analyze changes in bird populations across the continent. In a world of climate change and growing human populations, birds provide one of our best windows on we affect nature, and birders serve as the eyes and ears and the interested hearts of that effort.

Because the world keeps changing research never stops, but what keeps the scientist active also makes birding a continuing adventure, as much an exploration of nature as a matter of checking off species. Even on their home grounds birders see annual variation as birds expand their ranges or move out of their area, and occasionally the spectacular irruptions of new species or the occasional collapse of established ones. In the 1950s the self-introduced cattle egret spread through the country, and now the introduced Eurasian collared dove is doing the same. Cave swallows began nesting in the square drainage pipes under large highways, and ornithologists and birders remade their range maps. Recently West Nile virus devastated birds in many parts of the United States. As residues of the banned pesticide DDT leached out of the environment, bald eagles and peregrine falcons returned to parts of their old ranges, and now we can hope to see a eagle soaring over Minneapolis or an urban falcon taking a pigeon over Fifth Avenue.

Birders support conservation and work for it, but they go to the field because birds fascinate them, and here we come back to Bird Day’s original purpose — celebrating birds and inviting us to learn more. Those who want to learn about birds have many more resources than their ancestors. The few field guides available in 1894 treated a small selection of birds, had poor illustrations, and gave only hints about how to tell one bird from another—not surprising when even experts could not reliably distinguish all species in the field. Now every bookstore has shelves of guides with the latest tips on field identification, illustrated with digital photographs or expert paintings even more expertly reproduced, arranged to guide the reader to the right name, and catering to every interest and level of expertise. Roger Tory Peterson’s books, written for people with some experience but not a great deal, sit on bookstore shelves next to David Sibley’s guide, the National Geographic guide, and a dozen more for those who have outgrown “Peterson.” Further along we find volumes on identifying hawks at a distance or sorting out immature gulls, and a new form that offers on one page a dozen or more views of the species sitting, standing, and soaring — a miniature library of images. Audio guides make learning bird songs as easy as sorting out their distinctive plumages, and software puts field guides on our phones. Those tired of identification or just interested in birds in other ways can consult handbooks about birds’ lives, their evolution, and their development.

Birders can pursue their passion as far and in as many directions as they wish, for the hobby, though identified with listing, gives us a way to pay attention to the natural world. We can wander, study, and marvel in whatever ways attract us. It has never been a better or more important time to be involved with birds and never a better time to celebrate Bird Day.

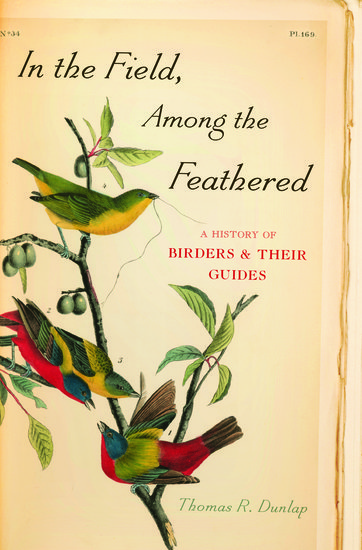

Thomas R. Dunlap is Professor of History at Texas A&M University, He is the author of In the Field, Among the Feathered: A History of Birders and Their Guides and Faith in Nature: Environmentalism As Religious Quest.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Both images in the public domain and courtesy of the author.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.