At 5:14 am GMT on March 20th the sun will cross the celestial equator going from south to north, signalling the beginning of spring in the planet’s northern hemisphere and autumn in the southern. We’re celebrating this astronomical event with Ian Ridpath and newly released NASA photos of the Moon.

By Ian Ridpath

When the last two astronauts left the Moon at the end of 1972, they probably thought that someone would be back in a decade or so to clear up the junk that was left behind. Half a century on, they — and we — are still waiting.

As a reminder of their exploits, we now have some impressive images of the six Apollo landing sites from a Moon-orbiting probe that has photographed the equipment they abandoned all those years ago.

Lower stages of the lunar landing modules, electrically powered Moon cars, scientific equipment, oxygen backpacks, and even trails of scuffed-up Moon soil where the astronauts walked and drove on the surface — they all show up, much to the dismay of those conspiracy theorists who have been trying to convince the gullible that humans never went to the Moon.

We owe these amazing new views to NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which has been spinning around the Moon since June 2009. Its original mission was to spy out new landing sites for future astronauts. But even while LRO was snapping the surface, President Obama cancelled NASA’s programme which was supposed to take humans back to the Moon. Ironically, LRO’s most memorable contribution has been surveying the old landing sites rather than spotting new ones.

Let’s go back to where it all began: Tranquillity Base on the Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquillity). Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed here in the lunar module Eagle on 20 July 1969. They were outside the lunar module for only about two hours so they didn’t have time to venture far, but they did plant a flag and set up experiments.

LRO took its first view of the site, as well as four others, in July 2009, in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing. In November last year it dipped down for a closer look. A new picture, just released, show not only the remains of the landing module but also equipment that had been put out on the surface by Aldrin such as a laser reflector for measuring the distance to the Moon, and a seismic experiment for detecting Moonquakes. Even the astronauts’ footsteps show up as dark trails in the lunar dust.

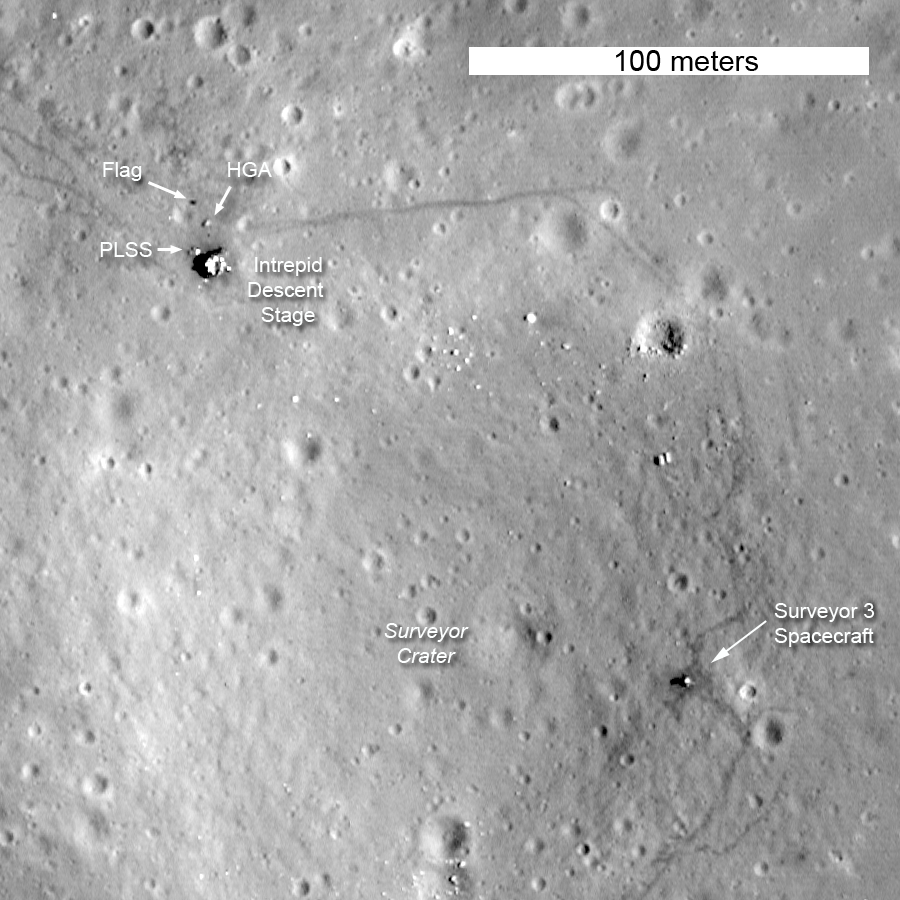

After the success of that first manned landing, NASA felt confident enough to aim for more interesting targets. One of my favourite missions was the second, Apollo 12 in November 1969, which touched down only a short walk away from an old robot probe, Surveyor 3, which had landed two and a half years earlier inside a shallow crater on the lunar plain called Oceanus Procellarum.

LRO pictures also released this month show the tracks of astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean as they walked from their lunar module around the crater rim to the dormant Surveyor 3. They snipped off the Surveyor’s camera and brought it back to Earth.

Apollo 13 in April 1970 was a near-disaster due to an onboard explosion on the way to the Moon, as dramatized in the film titled Apollo 13. The astronauts simply looped around the Moon and returned to Earth without landing. It wasn’t until the following January that flights resumed with Apollo 14, which visited an area near the centre of the Moon to sample rocks thrown out of the giant Mare Imbrium impact basin to the north.

On this mission, astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell were meant to walk from their lunar module to the rim of an impact feature called Cone Crater but it took them longer than expected. Unsure of their bearings, they turned back after reaching a boulder nicknamed Saddle Rock. From the LRO pictures we can see they were only about 100 feet away from their intended target.

The most spectacular landing site of all was visited by Apollo 15 at the end of July 1971: Hadley Rille, a snaking valley carved out by a lava flow. This mission was the first to use a battery-powered Moon car, called the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), which allowed the astronauts to drive to the edge of the rille. LRO’s most recent view of the Apollo 15 landing area shows the lunar rover parked on one side of the lunar module, with the scientific experiments on the other side.

The penultimate manned landing, Apollo 16, was the only Apollo mission to visit the lunar highlands. LRO’s most recent pictures of the site allow us to follow the routes that astronauts John Young and Charles Duke took during their exploration, which included sampling huge rocks.

Apollo 17 was the last and longest Apollo mission. Astronauts Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt spent 75 hours on the Moon, driving for some 35 km around their landing site. An enlargement of the descent stage of their lunar module, Challenger, even shows the two Portable Life Support System backpacks (PLSS) from their Moon

suits, discarded to save weight before take-off.

These LRO pictures remind us not only of the astronauts who risked their lives going to the Moon but the thousands of dedicated engineers, scientists and other unheralded workers who designed and built the craft that got them there and back safely. One day, tourists will visit the Moon to see for themselves these Apollo landing sites which are lasting monuments to the courage and ingenuity of those involved in one of the greatest achievements in the history of human exploration.

Ian Ridpath has been a full-time writer on astronomy and space since 1972. Many of today’s amateur stargazers learned their way around the night sky with his observing guides, such as The Monthly Sky Guide (CUP), now in its 8th edition, and the Collins Stars and Planets Guide (known in the US as the Princeton Field Guide to Stars and Planets). A particular interest of Ian’s is the Greek myths of the constellations, which he wrote about in his book Star Tales. Ian is editor of the authoritative Oxford Dictionary of Astronomy and is a former Council member of the Royal Astronomical Society. Learn more about lunar exploration and the Apollo Moon Landings.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

What a joke! Conclusive evidence? LMAO!! More like someone took their poor Photoshop skills and added dots to “objects” “left behind”. I could call those same objects proof that the Inhumans really live on the moon. But the comic book is as much a fairy tale as is the moon landing. And we are the gullible ones? Please.

Why can I google earth a satellite color image to my home from SPACE, but can’t see this “proof” as more than a couple grainy shadows?? I can’t get my cellphone to get a signal in my house, but we had perfect radio reception in the SIXTIES from the Moon?!? We can’t get to the bottom of the ocean, but we landed on the Moon…in the SIXTIES. Before digital watches were created? WOW!!!

[…] it as about the etymology of April. But it isn’t fortuitous that the festival is held at the vernal equinox, when “the earth opens to receive new fruit(s)” and the world rejoices. This is the time for […]