By G. Thomas Couser

Memoir gained sudden prominence in the mid 1990s, when a few memoirs by unheralded authors — Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, Mary Karr’s Liars’ Club, and Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted — had spectacular sales and favorable reviews. The memoir boom was underway.

Even before it was recognized as a boom, however, some intellectual heavyweights inveighed against it. Chief among them was William Gass, the title of whose screed in the Harper’s in 1994 says it all: “The Art of Self: Autobiography in an Age of Narcissism.” To write a memoir, Gass proclaimed, is to disclose oneself as a monster of egotism.

Name another genre — or for that matter, art form — that has been subject to such a blanket denunciation in our permissive era. (Okay, aside from rap music.)

To be sure, memoir cannot be entirely absolved of the charge of narcissism. It seems fitting, somehow, that the term contains the words “I,” “me,” and “moi.” Of course memoir is liable to suggest self-importance. But there’s more to good memoir than that.

And if we look at the larger picture, we can see why memoir endures and, in the end, resists blanket denunciation.

One way of looking at memoir–the more familiar one–is to think of it a literary genre. This is how most creative writers and literary critics view it–as a form of “creative nonfiction,” the “fourth genre” taught in MFA programs alongside the traditional three: fiction, poetry, and drama. The very name of this category, however, hints at memoir’s vulnerability. If “creative nonfiction” is not an oxymoron (it’s not), then the term belies a kind of uncertainty about its status as literature. Memoir suffers from the sense that it doesn’t quite belong among genres whose creativity can be taken for granted. As a literary genre, memoir suffers from an inferiority complex. After all, you don’t have to be a writer to pen a memoir; you don’t even have to write it yourself!

But memoir can also be looked at as the most literary form of something most of us engage in, actively or passively, most of our lives and even after our deaths. I refer here to what academics call “life writing.” It’s not a very satisfactory term — I prefer “life narrative” or even “life representation” — but it’s a useful one. Here are some things that constitute it: autobiography, biography, and memoir; diaries and journals; letters; portraiture, whether painted or photographic; biopics and bio-dramas; documentary films about individuals or groups of people; birth announcements, marriage announcements, and death notices; college application essays and school transcripts; personal ads; résumés; any kind of personal dossier; scrapbooks; anecdotes and family stories; family albums and home movies; People and Us Weekly; This American Life; the StoryCorps© project; anything on the Biography channel; personal email; most tweets; Facebook; last, but not least, gossip — the original social medium.

Life writing, then, refers to all the forms in which human lives get inscribed or represented, whether public or private, written or graphic, print or electronic, static or interactive. And the forms are constantly evolving and proliferating.

We are awash in self-representation. (Membership in Facebook is approaching one billion worldwide. And most users check their accounts daily.) Memoir may be a convenient scapegoat for our daily overexposure to the details of others’ lives. TMI!

But memoir’s weakness, from an aesthetic point of view — its location on the border between the literary and the quasi-, sub-, or outright nonliterary — is also its strength, from a more comprehensive perspective. William Dean Howells said it best over a hundred years ago, when he referred to it as “the most democratic province in the republic of letters.” It’s an inherently democratic genre, accessible to nearly everyone and thus inclusive of many different kinds of people. It’s the genre that best represents our individualistic, egalitarian ethos.

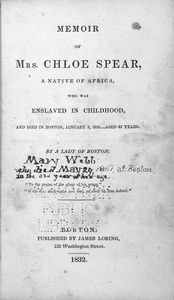

A quick and selective review of American literary history shows that it has long functioned as the threshold genre through which various minorities and marginalized populations have gained access to the realm of literature.

Of course, much memoir is self-aggrandizing and not worth your time. But before you dismiss memoir in its entirety, remember that it has served historically — and still functions — to make visible lives that once were lived in the shadows — or were considered not worth living, let alone writing.

G. Thomas Couser’s most recent book is Memoir: An Introduction. Recently retired after thirty-five years of college teaching, he lives in Connecticut, where he is working on a memoir of his father and a book about such memoirs.

[…] Why Memoir Matters (oup.com) Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

[…] notions of identity take on a curiously suspended form. What we now commonly refer to as ‘life writing’ has a peculiarly intense and self-conscious rendering in Irish literature, inspiring notable […]

[…] in origin. For an informed discussion of this type of writing, please come here – Why Memoirs Matter. This list will be updated as I come across additional titles. The enumeration is by name of the […]

[…] Read the Article Here! […]