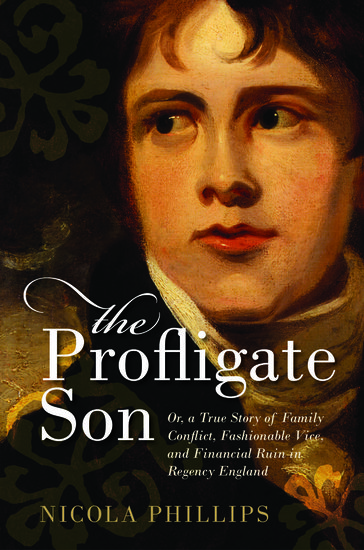

By Nicola Phillips

In eighteenth and early nineteenth-century England, prisons were popular tourist sites for wealthy visitors. They were also effectively run as private businesses by the Wardens, who charged the inmates for the privilege of being incarcerated there. Indeed prisoners from the higher ranks of society, who had the means to pay for better accommodation, routinely expected to be treated better than lower class or “common” criminals. Between 1810 and 1814, William Collins Burke Jackson, the son of a wealthy East India Company merchant, had the great misfortune of being able to sample the amenities offered to young gentlemen within five different penal institutions. Here is a brief tour of three of them.

The Fleet Debtors’ Prison

At just nineteen William was arrested by his creditors for debt and conveyed to Number 9 Fleet Market – a deceptively innocuous address that debtors’ used to conceal the fact they were actually residing within the Fleet prison. Visitors to the prison were so numerous that the guards memorised the faces of new inmates on arrival, so they could not walk out with the crowds. The range of accommodation a prisoner was offered depended on an assessment of “his rank and condition”. Rooms could be had on the Common side for poorer men or on the Master’s side for the wealthier, but there was a vibrant trade amongst officers and longer-term inmates eager to rent out rooms, or sub-let beds in them to new “chums” (so called because they had to pay “chummage” to the Warden). William’s accommodation tended to reflect the state of his finances. His father paid him a guinea a week which could provide lodging in a private room on the Master’s side, but when his funds ran low he was reduced to sharing a room without furniture on the Common side, or sleeping on a table in the taproom. He wanted to live outside the prison in an area known as “the Rules”. But it was an expensive privilege that required payment of securities to prevent prisoners crossing the invisible (and elastic) boundaries that ran down the middle of streets and buildings around the Fleet. An additional £5 would procure day release, ostensibly to sort out financial business, but it was more commonly known as “showing you my horse”, a phrase which reflected the more sociable activities made possible by such day trips.

Newgate prison was “of all places the most horrid”, but also highly recommended to tourists by London guide books. Its massive stone walls were built to hold around five hundred prisoners, but it frequently contained nearly double that number. In addition to tourists, there was a large daily influx of visitors: friends and family bringing food, prostitutes (pretending to be wives and paying “bad money” to the turnkeys to stay overnight), attorneys and gangs of thieves. The turnkeys insisted that leg irons were essential to distinguish inmates from visitors; but they also “loaded” prisoners with heavier irons so they could charge to change them for lighter shackles or to remove them for appearances in court. Despite this turnkeys had little control over the prisoners, who made their own rules and conducted mock trials of those that broke them. In 1811 the Warden admitted to Parliament there was “no discipline of any kind in Newgate.” William was at first confined to the Common Side with the “lowest and vilest” wretches who stole most of his clothing, but he eventually persuaded his father to pay for better lodging. Newgate had a Master’s Side where “more decent and better behaved” prisoners could share a proper bed, but the best rooms were on the State Side. Here, those “whose manners and conduct” proved they had received a good education could rent one of twelve rooms, and pay extra for a single bed and better food. Suspected felons were not supposed to be able to take advantage of this privilege, but despite the fact that his client had been charged with the capital crime of forgery, William’s solicitor discovered that payment of an extra guinea removed this obstacle.

“Retribution” Hulk

This aptly named prison hulk was moored on the Thames, close to the Woolwich Arsenal where its inmates were forced to labour while they waited to be transported to Australia. In spring and summer Retribution was a popular destination for tourists, who were curious to view its awful bulk and infamously depraved inmates from the safety of a small boat. From there they could also observe “the multitude of convicts in chains” working on the Warren. Retribution was one of the largest and longest-serving hulks with up to 450 men kept shackled below deck. Of all the hated hulks, this was the one prisoners dreaded most. The death rate on board was more than double that on the other hulks, and the number of attempted escapes was correspondingly high. There was no special accommodation available on board for gentlemen to rent, and William shared the “barley and putrid meat” the other convicts ate, which gave him such serious bowel problems he was sure it would soon “terminate [his] miserable existence”. He slept on straw with the other convicts, and no officers dared descend among them after dark, despite numerous reports of robbery, murder, suicide and “unnatural crimes”. Several attempts to seal off each of the three lower decks to reduce the incidence of crime and disease had failed because the convicts tore down the carpenters’ work every night. Efforts to erect a chapel on board were equally unsuccessful. William’s higher social status did, however, earn him kinder treatment from the ship’s officers. As a gentleman, he could and did seek help from influential friends in high places to gain a royal pardon, or permission to be transported on an earlier ship to Australia, but he was unsuccessful on both counts.

Nicola Phillips is an expert in gender history and a lecturer in the department of History and Politics at Kingston University. She is the author of The Profligate Son: Or, a True Story of Family Conflict, Fashionable Vice, and Financial Ruin in Regency England. Her research focuses on eighteenth-century gender, work, family conflict, and criminal and civil law. Nicola is also an advocate of public history, and has contributed to radio and TV programmes on gender history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Aquatint of Fleet Prison from The Microcosm of London or London in Miniature. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Newgate prison. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Discovery” at Deptford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[…] Read the full article here […]

[…] the darker side of Regency London? Try this post on a tour of Regency […]