By Ian Gadd

‘This Lane is commonly called Pie Lane, but I will call it Winking Lane’. So noted the Christ Church canon, Leonard Hutten, in his perambulatory Antiquities of Oxford, written at some point in the early seventeenth century. He was referring to Magpie Lane, which squeezes past Oriel College’s eastern flank on its way towards Oxford’s High Street. For Hutten, this lane deserved renaming ‘because the first Printing Presse, that ever came into England, was sett on worke in this Lane by Widdy kind, alias Winkin, de Ward [i.e. Wynkyn de Worde] a Dutchman.’

‘This Lane is commonly called Pie Lane, but I will call it Winking Lane’. So noted the Christ Church canon, Leonard Hutten, in his perambulatory Antiquities of Oxford, written at some point in the early seventeenth century. He was referring to Magpie Lane, which squeezes past Oriel College’s eastern flank on its way towards Oxford’s High Street. For Hutten, this lane deserved renaming ‘because the first Printing Presse, that ever came into England, was sett on worke in this Lane by Widdy kind, alias Winkin, de Ward [i.e. Wynkyn de Worde] a Dutchman.’

Hutten was not alone in seeking to claim Oxford as the first printing city of England. Brian Twyne, in Antiquitatis academiae Oxoniensis apologia (1608), makes a similar assertion although he identifies John Scolar rather than de Worde as the city’s first printer. However, the story took on new impetus in the 1660s when Richard Atkyns published an account of how Henry VI and Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury, had conspired to import the new technology of printing in England. In an audacious and expensive plot, a royal official and William Caxton, ‘a Citizen of good Abilities’, travelled abroad to kidnap one of Gutenberg’s workmen, one Frederick Corsells or Corsellis:

’Twas not thought so prudent, to set him on Work at London, (but by the Arch-Bishops means, who had been Vice-Chancellor, and afterwards Chancellor of the University of Oxford) Corsellis was carryed with a Guard to Oxford… So that at Oxford Printing was first set up in England, which was before there was any Printing-Press, or Printer, in France, Spain, Italy, or Germany, (except the City of Mentz)…

As evidence, Atkyns cited a hitherto unknown manuscript in Lambeth Palace as well as Expositio in Symbolum Apostolorum with its famous ‘1468’ Oxford imprint which, if accurate, would have predated Caxton’s first printed books by several years.

Atkyns was far from the disinterested scholar: the story formed part of a rhetorical and legal campaign to assert the primacy of the royal prerogative over the craft of printing in order to shore up Atkyns’s own claim to the patent for the printing of law books. Nonetheless, the Oxford myth proved proved enduring. Anthony Wood’s survey of printing in Oxford in his history of the University (1674) follows Atkyns’s account closely. Joseph Moxon includes the Corsellis story in his account of the origins of printing in Europe which prefaced his famous printing manual, Mechanick Exercises (1683–4). John Bagford’s early eighteenth-century account of Oxford printing also began with Corsellis, as did Samuel Palmer’s General History of Printing (1732). By the mid-century, Shakespeare was even being quoted as evidence: ‘thou hast caused printing to be us’d’ (Henry VI, part 2).

The Corsellis story was not just of scholarly interest. In 1671 Thomas Yate, the Principal of Brasenose College and one of the four ‘partners’ who managed the university printing and published in the 1670s, cited Corsellis, the ‘1468’ imprint, and the 1481 Oxford edition of Expositio super tres libros Aristotelis de anima in a legal defense of the university’s right to printing. In a court case a decade later, the King’s Printer Henry Hills used the same account to argue that his position trumped any printing rights claimed by the University. In a 1691 account of the recent conflict with the London book trade, the Keeper of the University Archives, John Wallis, declared that ‘the Art of printing was first brought into England by the University, and at their Charges; and here practiced many years before there was any printing in London…’ The Oxford story retained sufficient credibility to be cited in the court cases regarding copyright in the 1770s.

It was, though, a complete fabrication. The Lambeth Palace manuscript did not exist and the ‘1468’ imprint was almost certainly a misprint for 1478. Nor, for that matter, did de Worde, Caxton’s successor in London, ever print at Oxford. Nonetheless it would wrong to mock those who made these claims as charmingly naïve or as poor scholars. The Corsellis myth appealed as much to the hard-nosed pragmatist seeking to establish the University’s right to print whatever it liked as to the scholarly idealist who felt that printing’s beginnings in England ought to be found in the universities rather than elsewhere. Moreover, the potency of such beliefs reminds us that there may be other ‘myths’ about scholarly publishing at Oxford that, although not wholly false, deserve to be considered sceptically–whether it’s focusing on the three ‘great men’ of Oxford University Press’s early history (William Laud, John Fell, William Blackstone) at the expense of other important figures; whether it’s mischaracterizing the relationship between the London book trade and the university press as one in which a plucky Oxford repeatedly struggled for its rights against a gang of hostile and avaricious London booksellers; whether it’s forgetting that non-learned books have always been a crucial part of the university press’s output; or whether it’s assuming that the University’s scholarly aspirations as a publisher were repeatedly undercut by commercial imperatives. The history of Oxford University Press is much more complex than the mythology might have us believe.

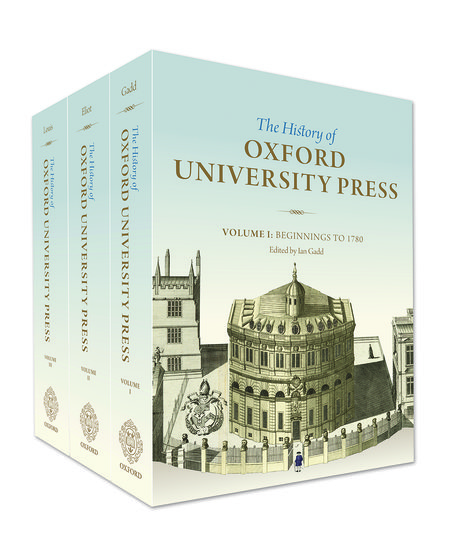

Ian Gadd is Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University. He is editor of The History of Oxford University Press–Volume 1: From its beginnings to 1780.

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Watch the silent film in our previous post.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of Magpie Lane, Oxford. Photo by Wikipedia user Newton2, 2005. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

[…] publications, trade, and international development. Watch the silent film or learn about arguments over the first printing press in Oxford in our previous […]

[…] trade, and international development. Watch a silent film, learn about arguments over the first printing press in Oxford and when the Press began, or discover printing in the Sheldonian Theatre in our previous […]