By Philip Schwyzer

What are we going to do with Richard III? More than a year after his bones were unearthed in Leicester, the last Plantagenet king is still waiting for a resting place. The initial plan, backed by the UK government and the University of Leicester, was that Richard’s remains should be interred in Leicester Cathedral, just a few hundred yards from the site where they were discovered. Yet a popular campaign on behalf of York Minster has sparked a fierce competition over these once reviled bones. Petitions on behalf of the rival cathedrals have each collected many thousands of signatures; a clutch of Richard’s distant relatives calling themselves the Plantagenet Alliance have demanded and been granted a judicial review. Meanwhile, Leicester Cathedral’s preferred design for the tomb — incised with a plain cross that seems to speak more of penance than of majesty — has so alienated some members of the Richard III Society that they have threatened to withdraw their promised donations.

The public squabble over some badly battered (but potentially lucrative) bones may not be very edifying, but it participates in a venerable tradition. For more than five hundred years, people have been arguing, sometimes violently, about the fate of Richard III’s remains. It came to blows in the city of York in 1491, six years after Bosworth. The schoolmaster John Burton, being “distempered with ale,” declared that Richard was “a hypocrite, a crouchback, and was buried in a dike like a dog.” Burton was then struck by another man, John Payntor, who insisted that Richard had not been buried like a dog, but “like a noble gentleman.”

The truth lay somewhere in between. For several days after Bosworth, Richard’s naked corpse had been placed on mocking display in a Leicester church. Analysis of the skeleton reveals the posthumous humiliation to which the body was subjected, including a sword-thrust through the buttocks. When the king’s remains received burial at last it was in a hastily dug grave — too short for his height — in the humble priory of the Greyfriars.

It took Henry VII ten years to provide his predecessor with an inexpensive tomb, adorned by a distinctly disparaging epitaph. A few decades later the priory was dissolved, and the king’s body disappeared, apparently forever. In Shakespeare’s day it was rumoured that Richard’s exhumed corpse had been dragged through the streets by a jubilant mob and thrown in the River Soar.

Shakespeare was perhaps aware of the questions and controversies swirling around the fate of Richard’s remains. At the conclusion of his Richard III, the defeated tyrant’s body is simply left on stage (or, as in the recent production with Kevin Spacey in the title role, winched up to dangle ominously over the heads of the victors). Shakespeare has the victorious Henry give explicit commands regarding the burial of other combatants, but nothing is said about Richard. There is an ironic disjunction between the play’s relentless focus on Richard’s deformed body, which seems almost a character in itself, and the silence which surrounds his corpse at the end.

Richard’s modern admirers are apt to condemn Shakespeare for his depiction of the king as a hunchbacked psychopath. Yet if Shakespeare created a monster, he is also largely responsible for our enduring fascination with the figure of Richard III. And if Shakespeare’s play is full of fabrications, it is also suffused with genuine fragments and traces of Richard’s era. Much as the stones of the dissolved Greyfriars were employed to repair and expand the nearby church that became Leicester Cathedral, Richard III gathers up stray pieces of language, memories, and customs and assembles them in a new context. Even the century-old words of a drunken York schoolmaster find an echo in the play, wherein Richard is repeatedly likened by his enemies to a dead dog.

Shakespeare’s Richard III is, among other things, a play about the difficulty of laying the dead to rest. Significantly, it is Richard himself who is keenest to provide his victims with a final burial, imagining that the claims of the dead end with their interment. “I’ll turn yon fellow in his grave,” he says of the murdered Henry VI, “And then return lamenting to my love.” When the assassin Tyrrell assures him that the Princes in the Tower are dead, he presses “And buried, gentle Tyrrell?” Yet on the night before Richard’s own death in battle, these victims and more arise from their supposedly secure graves to pronounce vengeance upon him. As Richard learns too late, there is little point in shoving bodies under the earth when the longings and grievances of the past remain abroad.

Might Shakespeare’s play have something to whisper to those now seeking to claim Richard’s remains for Leicester or for York? Could we be a little naïve in imagining that interment in one cathedral or another will settle our accounts with him and with his age? Experience shows that burying Richard III has never been a very effective way of getting him to rest in peace. The modern world is shot through with particles and traces of his troubled times, some of them preserved in Shakespeare’s play, some in the unresolved legacy of conflict between north and south, some in the very legal system to which we turn to decide what to do with his remains. Wherever his bones come to rest this time around, Richard III will not cease to be our contemporary.

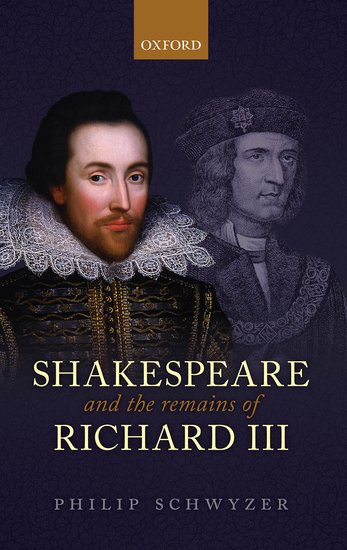

Philip Schwyzer is Professor of Renaissance Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of the book, Shakespeare and the Remains of Richard III.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) The proposed design for the tomb of Richard III in Leicester Cathedral. By permission of architects van Heyningen and Haward; (2) Human Remains found in trench one of the Grey Friars dig. A11-2012-SK1-19e. By permission of the University of Leicester. Do not reproduce either image without permission.

I’ve always thought of Richard III as a son of the north country–York, to be specific. And I can imagine that when/if he thought of his death, he imagined his remains resting there. Why anyone would think it a good idea to inter his remains at a site where, as you write, his naked corpse had been put on display and humiliated is beyond me. I guess money–in this case the money to cover the archaeological dig–can buy just about anything.

The most unedifying aspect is not the conditions of his initial burial, but the manner in which grubby lawyers have intervened, in the now too familiar ‘InjuryLawyersRus-esque’ fight to wrestle the last remnants of any dignity which may have been afforded the reburial !

[…] III has been much in the news of late: his body was recently found under a parking lot, buried with a horse and showing signs of […]