By William Todd Schultz, PhD

Why did Truman Capote try writing his last unfinished book, Answered Prayers? In a sometimes ruthless sautéing of jet set high society, he oddly and self-destructively scorched many of his closest friends, women like Babe Paley and Gloria Vanderbilt, among unlucky others, whom he liked to call, in a better mood, his “swans.” It turned out to be a sideways suicide. He never recovered from the fallout. His last years were a hurricane of drink, drugs, and artistic fragmentation.

In working to understand Capote — his childhood, his memories, his relational strategies — it is necessary to come to some kind of terms with a feature of his life that seemed, on its face, rather squirrely. He lied. Or to put it less baldly, he felt zero obligation to stick to the facts. The story was the thing. Getting the details of the story right came a distant second, always. So what to do? Can one write a psychobiography of a born fictionalizer, a person for whom the past is endlessly malleable, improvable?

My answer to the first question is: who knows? My answer to the second: no, it doesn’t. Now, this might seem cavalier. Aren’t psychobiographers supposed to care about the facts? Yes, facts are crucial. Facts are the instruments of revelation. I love facts. But the reality is, remembered life is itself fiction, a constantly evolving construction. That being so, the raw material one works with is best approached as a “faction” — a composite of artful narrative and quantifiable life-history. And given the unreliability of memory, especially in someone like Capote, who saw his past as perfectible, all one can do is dive into the messy blurriness.

The hotel lock-in may have been partly imaginary, it may have been entirely imaginary. In either case, it was psychologically real. Capote told the story over and over because it captured something essential about his emotional life; it summed up, in one neat mobile package, who he was and why he did what he did. Capote, no doubt, would have sided with fellow raconteur Oscar Wilde, according to whom truth was “entirely and absolutely a matter of style.”

Capote also fibbed about Answered Prayers. He exaggerated its length, described chapters that hadn’t even been written. Here again, the question isn’t did he really write it, but why he felt the need to pump it up, pretend it was more than it was. To Capote, words were power. The book had to exist, because without it, he didn’t.

In some ways the lie is more important than the truth. The lie is fantasy, and fantasy is creative product, yet another work of art to dissect and interpret. People kill themselves over false memories. That fact alone makes it clear that false is anything but. It’s a question of the value of the memory, not its accuracy.

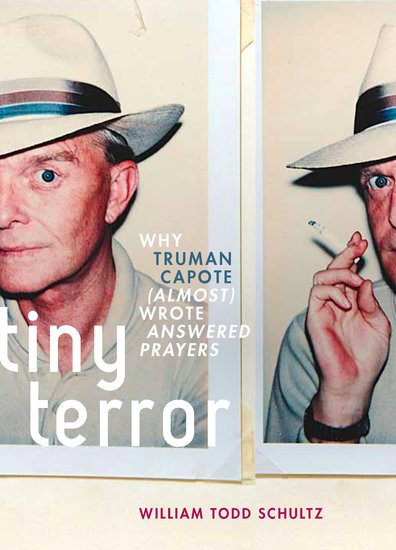

William Todd Schultz, PhD, is Professor of Psychology at Pacific University in Portland, Oregon, and author of Tiny Terror: Why Truman Capote (Almost) Wrote Answered Prayers. Over the past two decades he’s written numerous psychobiographical articles and book chapters, on Ludwig Wittgenstein, Diane Arbus, Sylvia Plath, Oscar Wilde, Roald Dahl, James Agee, and Jack Kerouac, among others. He is editor of the Handbook of Psychobiography (Oxford University Press, 2005) and the Inner Lives series for Oxford, author of An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus (Bloomsbury, 2011), and is currently writing a biography of musician Elliott Smith.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Author photo courtesy of JJ Gonson Photography.

[…] post at Oxford University Press blog, on my Capote book and Capote’s artful lies. Read it HERE. Like this:LikeBe the first to like […]

The most artful lie of all could be his authorship of Harper Lee’s only claim to fame. Just a thought…..

[…] chiedendo, e quindi? Quindi, casualità vuole che il giorno dopo io sia incappata in questo articolo segnalato dal New York Times; si tratta di un pezzo di William Todd Schultz, Professore di […]