By Eric Sandweiss

In 1938, Charles Cushman commenced his Kodachrome journey across America. At the same time, architects and city planners began to extend the tools of historic preservation beyond their original applications. From Santa Fe to Charleston, city councils experimented with new powers, daring to extend protections once reserved for isolated battlefields, Great Men’s homes, or government buildings to include entire neighborhoods. They argued that the public benefit derived from preserving architectural character outweighed an individual owner’s rights to do with his property what he wished. Federal relief funds paid architects to measure aging buildings, writers and photographers to survey historic districts, real estate analysts to assess urban housing stock. Suddenly, the inner city seemed an interesting place.

The preservation boom grew from the development bust. Had falling property values (particularly in the central cities) not threatened public coffers and private fortunes, it’s hard to imagine that American investors would have thought twice about the potential value of those sites that had yet survived the developer’s natural and longstanding inclination to demolish, rebuild, densify, intensify. Seeking virtue in necessity, landowners and civic officials worked on two fronts from the 1930s through the postwar years. They sought incentives for blighting and demolishing some declining properties, while they reimagined others as sites of “gracious living” and “gaslit elegance,” or as “proud reminders of a bygone era.” They counted on the new preservation ordinances to minimize the risk then associated with choosing maintenance and restoration over new construction.

Walking the streets of Albuquerque, New Orleans, Savannah, and other aging cities in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, Cushman fixed his lens on buildings that would soon find their way into both categories. His photographic remembrance of things past took him both to future redevelopment sites and to future showcases of preservation. In recent weeks, retracing the amateur photographer’s routes through the Southwest and California, I am reminded that the two paths to midcentury urban redevelopment — preservation and demolition — more often complemented than conflicted with one another. Preservation controversies were settled as often by gentleman’s agreement in the city council chamber as they were by grassroots protest in the street.

Albuquerque’s Old Pueblo, protected (and fixed up) in the 1940s to expand tourist and commercial trade from the city’s distant downtown, still functions in much the way it was intended — leveraging the city’s Hispanic heritage to add commercial vigor to an aging west side neighborhood. Along San Francisco’s Embarcadero, a workday army of technology and marketing professionals crosses the pedestrian landscape of Levi’s Plaza — ground that once knew the heavy bootsteps of longshoremen and the rumble of trucks. In Los Angeles, the return of the Angels Flight funicular up the side of Bunker Hill adds a touch of historical continuity to a part of town otherwise unrecognizable from Cushman’s day, and in the process seeks to connect the commercial success of the redeveloped landscape atop the hill with the more depressed downtown zone of Hill, Broadway, and Main Streets, lying to its east.

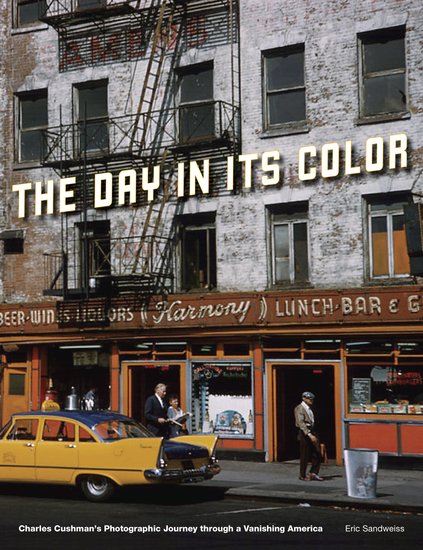

Like most Americans of his day, Charles Cushman was neither preservationist nor modernist. He enjoyed pieces of both past and present, using his camera to assemble a picture of his “day in its color,” and seldom peering incisively into the shadows of class or race inequality or environmental degradation that lay beneath its surface. Cushman does not ask that we rush to his side in defense of these sites of imminent change, but neither do his pictures suggest confidence that something better awaits. His job (and his real job, at that) was to predict where the market was headed, not to take it there.

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Eric’s next and last appearance will be a book talk at Left Bank Books in Saint Louis, MO on June 21 at 7:00 p.m. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color” and “Bits and Pieces of the Mother Road.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art & architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.