By Eric Sandweiss

Route 66 is more famous and less necessary than ever. Gray-haired couples on motorcycles cruise past its boarded-up motels. Families stop at themed rest areas to eat at picnic stands shaped to resemble the iconic roadside attractions that the decommissioned highway no longer supports. Historic markers draw curious travelers off the interstate and onto meandering two-lane roads that peter out in quiet small-town Main Streets.

John Steinbeck’s 1938 Dust Bowl novel, The Grapes of Wrath, helped to turn this thin strip of graded concrete from a numbered piece of federal property into a character in the American family romance. Just as important to this transformation are the early depictions of the road left by its uncelebrated travelers, including the novelist’s first cousin by marriage, photographer Charles Cushman.

I-44 Conway Welcome Center, Conway, MO. Photos by Eric Sandweiss

From the 1930s through the 1950s, Cushman often traveled back and forth along the same route as the Joads, not in an overladen truck but in shiny late-model Ford coupes. While Steinbeck typed up his impressions along the way, Cushman did his thinking with a camera. He recorded sporadically rather than systematically, offering occasional glimpses rather than a coherent narrative. (For that bigger picture, one has to look at his entire work — three decades of picture-taking carried out across a half-million driving miles).

Cushman never, to my knowledge, climbed atop a Harley. He certainly never sported a gray pony tail, but he was among those (including, eventually, cousin John himself in the late road narrative, Travels with Charley) who saw travel along the US highways as an occasion for pleasure and discovery in its own right. Lacking his cousin’s early passion for social critique, or the artistic sensibility of a Robert Frank (who traveled many of the same routes in the 1950s) Cushman stopped here and there as the mood struck him, much as holiday and leisure travelers have done before and since.

Traveling Cushman’s route west in the past week, I am struck both by how full and how fragmented our view of the American roadscape has become. Route 66 exists so completely in our literary memories, our imaginations, our online search options, that even the faintest of efforts can serve to satisfy the curiosity that took a man of his generation many years to settle. As with every other aspect of our networked world, such access cuts both ways. While access to information democratizes our ability to fashion a coherent picture of the landscape, it furthers the atomization of our social and spatial selves. Locked in our homes, we open Google Maps for a 360-degree view of any square foot of the highway. On our GPS devices and our Mapquest searches, we break down the full experience of travel into a million randomly ranked impressions; “continue west 734.5 miles” takes up less space in our brains than “south 37 feet to unmarked intersection, take a soft right onto eastbound access road.” We know everything and we know nothing about the spaces through which we move.

El Vado Motel, Central Ave. (US Highway 66), Albuquerque, NM. Photos by Eric Sandweiss.

Today’s Route 66 is broken into pieces and symbols, shorn of its practical functions even as it is elevated in its “imageability.” To an extent I have to blame not just Steinbeck but Charles Cushman and the millions like him — men and women who accepted the challenge that car companies, chambers of commerce, and camera manufacturers across America laid before them. “See the USA” and appreciate the road — as I am on my own drive this month — not for what it enables us to accomplish as a society, but for what it allows us to experience as individuals.

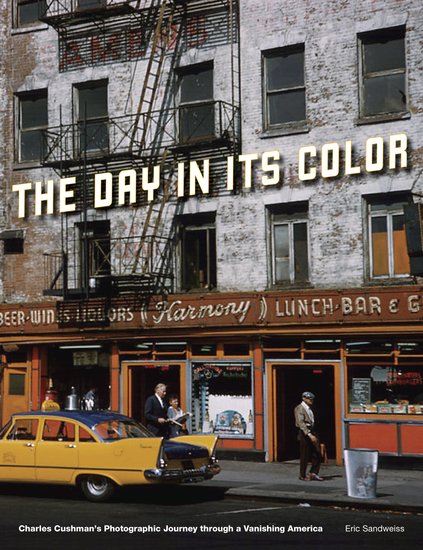

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Read his previous blog post “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art & architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Telegraph Hill from the Embarcadero. Source: Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, Indiana University.Telegraph Hill from the Embarcadero, 2006. Photo by Eric Sandweiss. Like most Americans of his day, Charles Cushman was neither preservationist nor modernist. He enjoyed pieces of both past and present, using his camera to assemble a picture of his “day in its color,” and seldom peering incisively into the shadows of class or race inequality or environmental degradation that lay beneath its surface. Cushman does not ask that we rush to his side in defense of these sites of imminent change, but neither do his pictures suggest confidence that something better awaits. His job (and his real job, at that) was to predict where the market was headed, not to take it there. Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Eric’s next and last appearance will be a book talk at Left Bank Books in Saint Louis, MO on June 21 at 7:00 p.m. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color” and “Bits and Pieces of the Mother Road.” […]