By Edward Shorter and Susan Bélanger

In the fifty years since the publication of A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess’s dystopian fable remains by far the best-known of his more than 60 books. It also remains controversial and widely misunderstood: assailed for inciting adolescent violence (especially following Stanley Kubrick’s explicit 1971 film adaptation) or viewed as an anti-psychiatry treatise for presenting behavioural conditioning as an instrument of social control. But this aspect of the book needs to be seen within a broader context.

In the fifty years since the publication of A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess’s dystopian fable remains by far the best-known of his more than 60 books. It also remains controversial and widely misunderstood: assailed for inciting adolescent violence (especially following Stanley Kubrick’s explicit 1971 film adaptation) or viewed as an anti-psychiatry treatise for presenting behavioural conditioning as an instrument of social control. But this aspect of the book needs to be seen within a broader context.

Let’s take a look at the anti-psychiatry case. The protagonist Alex — convicted of murder following a brutal home-invasion — is offered early release for submitting to a conditioning process called the Ludovico Technique.

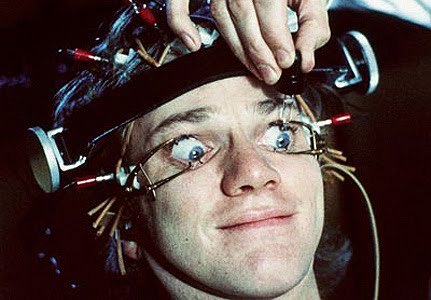

Transferred to a “new white building” resembling a private clinic, Alex believes he has fooled the authorities into releasing him after he watches some “films” and receives vitamin shots. Then the tables are turned. The “vitamins” leave Alex groggy and increasingly sickened as he is subjected to an endless series of violent images while strapped into a chair, his eyelids pinned wide open. Wired up with electrodes, he decides the doctors “and the others in white coats” — including a technician callously “twiddling with the knobs and watching the meters” — are worse than the criminals they seek to reform. The clinicians, however, rationalize their actions as therapeutic and Alex’s reactions a sign of improvement: “You are being made sane, you are being made healthy.”

Alex discovers the injections are a form of aversion therapy, administered along with scenes of Nazi atrocities and (as an unintended side-effect) the final movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The doctors, unmoved by music except as “a useful emotional heightener,” dismiss his outrage. “Now we can be perfectly clear about it. We can get this stuff of Ludovico’s into your system in many different ways…. But the subcutaneous method is the best. Don’t fight against it.” Resistance is met by force, with burly attendants pinning him down while the nurse jabs him “real brutal and nasty. And then I was wheeled off exhausted to this like hell sinny [cinema] as before.”

After the drugs are discontinued the forced viewings, and Alex’s nausea, persist. Once rendered physiologically incapable of all aggression, he is paraded before an audience of prison officials and politicians. His complaint, “Am I like just some animal or dog?” (echoing I.P. Pavlov’s conditioning studies) is dismissed with the reminder that he volunteered for the treatment and the results are “a consequence of your choice.” This so-called choice was merely a form that Alex signed without understanding the details; Burgess raises the question of informed consent. This concept, just emerging in the late 1950s, has been a hot-button issue in psychiatry ever since.

Political interest in behavioural programming is represented by the Minister of the Interior (whom Alex nicknames Minister of the Inferior, or — in a nod to the truncations of George Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984 — Int Inf Min). The “Min” visits the prison to implement the treatment in order to fight crime “on a purely curative basis. Kill the criminal reflex.” He reappears as Alex’s “cure” is demonstrated and boasts to the media about government efforts to suppress “young hooligans and perverts and burglars.” In fact the police are now recruiting former hooligans to rough up whomever they choose and round up enemies of the Government, an agenda suggested by the Minister’s earlier comment about clearing the prisons for “political offenders.” This combination of political tyranny and abusive (Pavlovian!) conditioning in a future Britain where adolescent thugs speak a mixture of Cockney rhyming slang, archaisms, and anglicized Russian (“Propaganda. Subliminal penetration,” a doctor suggests) creates an additional sinister note that would have been especially potent in the Cold War era when A Clockwork Orange was published.

Yet the political angle shouldn’t be overplayed. Despite superficial parallels with French philosopher Michel Foucault’s assault on psychiatry as an agency of social control in Folie et déraison (Madness and Unreason), published in 1961, Burgess was no anti-psychiatry theorist. His interests lay elsewhere. John Burgess Wilson (1917–93) was a self-taught linguist and composer with a literary background. A lapsed Catholic, he remained drawn to such moral issues as good and evil, free will, and social control. A full-time writer and critic since the late 1950s, Burgess was eulogized in The Times as “a great moralist.”

Of equal interest here is the actual psychiatric backdrop to Clockwork in 1960s Britain. Psychiatry was in the middle of dramatic change. Mental hospitals were reforming, bringing in open-door policies and putting the nurses in jeans rather than whites. A series of highly-effective physical treatments had been introduced in the 1930s — insulin coma, chemical convulsion, and electroconvulsive therapy — and by the 1950s ECT was in common use. The optics of these interventions were horrible, as Burgess clearly recognized, but they made patients better and didn’t “torture” or “brainwash” them as anti-psychiatrists (or the entirely fictional Ludovico regime) alleged.

Beginning in the 1950s, a series of revolutionary drug treatments arose: antipsychotics, antidepressants and anxiolytics. So widespread was their use that, by the time Burgess penned Clockwork, they had become the subjects of cocktail party chitchat. Medical psychotherapy, which had ruled the roost in previous decades, was wobbling (the Brits never had much interest in Freud’s psychoanalysis) and was about to be pushed out the door. All these innovations lent themselves marvelously to being parodied, sent up, and pulled down by scornful novelists.

That’s the social backstory. In the light of Burgess’s own backstory, the central message in A Clockwork Orange is voiced by the Prison Chaplain, who questions whether it is better for a man to choose evil rather than having “the good imposed upon him,” and ultimately leaves the prison service to speak out against the Ludovico Treatment. The key image is thus that of the title (and dissident F. Alexander’s treatise), which defines “a clockwork orange” as “The attempt to impose upon man… laws and conditions appropriate to a mechanical creation.”

Edward Shorter is Jason A. Hannah Professor in the History of Medicine and Professor of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. He is the author of numerous books on psychiatric history including A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry and Before Prozac. Susan Bélanger is Research Coordinator with the History of Medicine Program, University of Toronto, and a long-standing fan of speculative fiction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

psst…That’s the Final Movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, not Fifth.

@betasheep

Thanks for the comment. However, this is one of the book versus movie confusions. In the book, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is used as a soundtrack to one of the Ludovico films. In Stanley Kubrick’s film, the Ninth Symphony was used.

— Blog Editor Alice

[…] The most imaginative medical application of Alice in Wonderland, however, occurs as the jocular prologue to a more serious examination of breathing disorders described in several of Shakespeare’s historical dramas. In an essay titled “Sleep of the Great,” published in 2000 in the journal Respiratory Physiology, William A. Whitelaw and A.J. Black of the University of Calgary identify the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party as an early report of obstructive sleep apnea and its treatment. “You might just as well say… that ‘I breathe when I sleep’ is the same thing as ‘I sleep when I breathe’” says the Dormouse (“which seemed to be talking in its sleep”), to which the Hatter replies “It is the same thing with you.” Whitelaw and Black interpret the Dormouse’s “severe daytime somnolence” as “a cardinal symptom of obstructive sleep apnea…. The dormouse cannot breathe and sleep at the same time because… his pharynx falls closed the moment he falls asleep.” The episode ends with Alice walking off in disgust (“It’s the stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life!”) as the Hare and the Hatter stuff the Dormouse head first into a teapot. Referring to the accompanying illustration by Sir John Tenniel, Whitelaw and Black explain that the teapot “fits tightly around his neck, thus compressing the air in the pot and producing continuous positive airway pressure, which is the best treatment for obstructive sleep apnea.” Edward Shorter is Jason A. Hannah Professor in the History of Medicine and Professor of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. He is the author of numerous books on psychiatric history including A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry and Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry. Susan Bélanger is Research Coordinator with the History of Medicine Program, University of Toronto, and a keen student of interactions between literature and medicine. Read their previous blog post on “Anti-psychiatry in A Clockwork Orange.” […]

This book is one of my all time favorites. It has a glossary to define the slang which was very helpful, as were your insights. Listening to the lovely Ludwig brought me here.