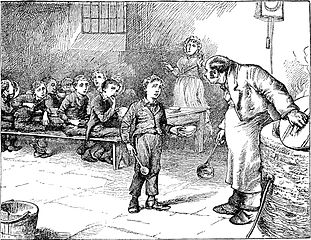

With the bicentenary of Charles Dickens‘ birth on the 7th February, here is an excerpt from one of his most popular novels, Oliver Twist, part of our Oxford World Classics series. The story of Oliver, who suffers a miserable existence in a workhouse and later escapes to London, is an unromantic portrayal of criminals, gangs, and the cruel treatment of orphans in Victorian London. Here we see Oliver in a vulnerable state in the workhouse before he is made aware of what his future holds. This month, OUP also publishes Dickens and the Workhouse: Oliver Twist and the London Poor which gives an historical insight into the real lives of people who Dickens based his characters on. And now on to Oliver. –Alice

Oliver had not been within the walls of the workhouse a quarter of an hour; and had scarcely completed the demolition of a second slice of bread; when Mr. Bumble, who had handed him over to the care of an old woman, returned; and, telling him it was a board night, informed him that the board had said he was to appear before it forthwith.

Oliver had not been within the walls of the workhouse a quarter of an hour; and had scarcely completed the demolition of a second slice of bread; when Mr. Bumble, who had handed him over to the care of an old woman, returned; and, telling him it was a board night, informed him that the board had said he was to appear before it forthwith.

Not having a very clearly defined notion of what a live board was, Oliver was rather astounded by this intelligence, and was not quite certain whether he ought to laugh or cry. He had no time to think about the matter, however; for Mr. Bumble gave him a tap on the head, with his cane, to wake him up: and another on the back to make him lively: and bidding him to follow, conducted him into a large whitewashed room, where eight or ten fat gentlemen were sitting round a table. At the top of the table, seated in an arm-chair rather higher than the rest, was a particularly fat gentleman with a very round, red face.

‘Bow to the board,’ said Bumble. Oliver brushed away two or three tears that were lingering in his eyes; and seeing no board but the table, fortunately bowed to that.

‘What’s your name, boy?’ said the gentleman in the high chair.

Oliver was frightened at the sight of so many gentlemen, which made him tremble; and the beadle gave him another tap behind, which made him cry; and these two causes made him answer in a very low and hesitating voice; whereupon a gentleman in a white waistcoat said he was a fool. Which was a capital way of raising his spirits, and putting him quite at his ease.

‘Boy,’ said the gentleman in the high chair, ‘listen to me. You know you’re an orphan, I suppose?’

‘What’s that, sir?’ inquired poor Oliver.

‘The boy is a fool – I thought he was,’ said the gentleman in the white waistcoat.

‘Hush!’ said the gentleman who had spoken first. ‘You know you’ve got no father or mother, and that you were brought up by the parish don’t you?’

‘Yes, sir,’ replied Oliver, weeping bitterly.

‘What are you crying for?’ inquired the gentleman in the white waistcoat. And to be sure it was very extraordinary. What could the boy be crying for?

‘I hope you say your prayers every night,’ said another gentleman in a gruff voice; ‘and pray for the people who feed you, and take care of you – like a Christian.’

‘Yes, sir,’ stammered the boy. The gentleman who spoke last was unconsciously right. It would have been very like a Christian, and a marvellously good Christian, too, if Oliver had prayed for the people who fed and took care of him. But he hadn’t, because nobody had taught him.

‘Well! You have come here to be educated, and taught a useful trade,’ said the red-faced gentleman in the high chair.

‘So you’ll begin to pick oakum to-morrow morning at six o’clock,’ added the surly one in the white waistcoat.

For the combination of both these blessings in the one simple process of picking oakum, Oliver bowed low by the direction of the beadle, and was then hurried away to a large ward: where, on a rough hard bed, he sobbed himself to sleep. What a noble illustration of the tender laws of England. They let paupers go to sleep!

Poor Oliver! He little thought, as he lay sleeping in happy unconsciousness of all around him, that the board had that very day arrived at a decision which would exercise the most material influence over all his future fortunes. But they had.

Charles John Huffam Dickens (1812–1870), novelist, was born on 7 February 1812 at 13 Mile End Terrace, Portsea, Portsmouth, the second child and first son of John Dickens, an assistant clerk in the navy pay office, stationed since 1808 in Portsmouth as an ‘outport’ worker, and his wife, Elizabeth, née Barrow. There can be few other English writers — apart, of course, from Shakespeare — with such widespread influence as Dickens, not only on their successors in the national literature, but also on major foreign writers, and few have been the subject of so many outstanding treatises by foreign critics. Oliver Twist, is one of his most popular and personal works. Dickens and the Workhouse: Oliver Twist and the London Poor presents the story of the discovery that as a young man Charles Dickens lived only a few doors from a major London workhouse for the first time, and shows that the two periods Dickens lived in that part of London – before and after his father’s imprisonment in a debtors’ prison – were profoundly important to his subsequent writing career. Happy 200th Charlie!

DICKENS IS ARGUABLY THE MOST POPULAR OF ALL ENGLISH NOVELISTS TILL DATE!THIS ENDURING ENIGMA OF CHARLES DICKENS IN ITSELF IS A TELLING EXAMPLE OF WHO HE WAS N WHAT HE MEANS TO THE READER TODAY -200 YEARS AFTER HE WAS BORN ON 7TH FEBRUARY 1812 IN PORTSMOUTH,ENGLAND!

DICKENS WAS THE MAIN REPRESENTATIVE VOICE OF WHAT WE CALL ‘VICTORIAN-ERA’ OR ‘VICTORIANISM’ OR ‘VICTORIANA’!

HE WAS VERY KEEN OBSERVER OF HIS TIMES AND THE ABSURDITIES THEREOF!A GREAT HUMANIST,DICKENS PORTRAYED SOCIAL EVILS AND SOCIETAL ILLS OF HIS TIMES IN GREAT ACCURATE DETAILS.HE WAS NOT A PREACHER,THOUGH. . .JUST AN AUTHENTIC SPOKESMAN OF THE VICTORIAN BRITAIN.

HIS NOVELS LIKE ‘ OLIVER-TWIST’ WERE VERY INSTRUMENTAL IN HASTENING REFORMS LIKE THE LITERACY,LABOR REFORMS!WHEN HE WROTE HIS FIRST NOVEL, THE BRITISH LITERACY RATE WAS AROUND 50 PERCENT. . .WHEN HE DIED AT D AGE OF 58,THE LITERACY RATE WAS IN NINETIES!

In order to celebrate Dickens’s bicentenary, I’ve just made the commitment to read as many of his classics as possible – starting with Oliver Twist! Thanks for the excerpt to get me on my way, I look forward to a year of literary indulgence :)