By Paula A. Michaels

Writing on Saturday in The Age, popular historian Paul Ham launched a frontal assault on “academic history” produced by university-based historians primarily for consumption by their professional peers.

In his article, Ham muses on whether these writings ever “enlightened or defied anyone or just pinged the void of indifference” Lamenting its alleged inaccessibility and narrow audience, Ham asks with incredulity:

What is academic history for?

Ham’s is only the latest in a steady stream of attacks castigating historians and other scholars for their inability to engage the general public effectively. New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof sent American academia into a collective apoplectic fit with a February column imploring academics to make a greater contribution to policy debates as public intellectuals.

Less convinced than Ham of the purposeful obscurantism of academic writing, Kristof nonetheless met with a sharp rebuke from the academy, which defended its track record for engagement and faulted Kristof for pointing only to the highest profile venues to judge scholars’ participation in debates beyond the Ivory Tower.

As political scientist Corey Robin observes:

there are a lot of gifted historians. And only so many slots for them at The New Yorker.

Scholar-turned-Buzzfeed-contributor Anne Helen Petersen notes that, in combination with a shortage of academic jobs, “the rise of digital publishing has ironically yielded an exquisite, flourishing community of public intellectuals”, as The Conversation itself attests.

But the opening up of a raft of new, online avenues for smart, serious commentary and analysis has no corollary in the book business. If Kristof’s cardinal sin is an elitist reluctance to look beyond the most venerable establishment periodicals, Ham’s central failure is a seemingly wilful blindness to the role market forces play in the publishing industry.

Academic historians fail to make their way into Amazon’s Top 100 list not because they are unable or, as Ham asserts, unwilling to write accessibly. I doubt there are many academic historians who, whether out of passion for their subject or sheer ambition, would turn down the opportunity to enjoy a moment in the limelight.

But the path of popular history is closed to most historians because of the very subjects of their investigation. No amount of finesse with the written word would have put my first book, on the history of medicine and public health in Soviet Kazakhstan, on the shelves of Dymock’s. The publishing of popular history is driven not by how scholars write, but by what readers are willing to buy.

Is there value to scholarship that falls outside the narrow parameters of what is financially feasible for a commercial press? Of course there is, not least because scholarly studies, though often narrowly conceived, nonetheless inform the work of those engaged in topics of broader interest.

Take, for example, the work of popular American presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. She investigates first-hand the relevant primary sources, but she also supports her analysis by drawing on works that delve deeply into the more slender crevices of history. The research of perhaps hundreds of historians informs her understanding of the world in which her protagonists operate.

No-one would expect every scientist to produce work that was at once highly sophisticated and accessible to the lay reader. There is a depth and detail of analysis that is only of interest to the specialist but necessary for the field’s advancement; we value American astrophysicist Neil Degrasse Tyson’s ability to distill that vast, dense body of scholarship and present it to us with crystal clarity on the TV series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey.

And when he turns to evolutionary biology, far from his own area of expertise, he leans entirely on the research of others. Similarly, Kearns Goodwin and her fellow popular historians rely on the solid, vetted works of academic historians to tell their more accessible stories for popular audiences. That act of translation does not render the original scholarship superfluous, but rather attests to its impact.

Publications are, of course, only one measure of public engagement. Through work in the classroom, academic historians translate and interpret scholarly writings for and alongside students.

They are also out in the community, sharing their expertise in public talks designed for general audiences at museums, at schools, at retirement communities, and elsewhere, such as at the Making Public Histories Seminar Series run by Monash University and the History Council of Victoria and held at the State Library of Victoria.

Not only are academic historians clearly far more engaged with the public than they appear at a first, blinkered glance, but there seems to be ample room for and value in a wide range of intellectual activity. Perhaps it’s time to set aside pot shots and straw men and recognise that the changing terrain of public engagement allows for a multiplicity of voices and forms of expression.

It’s not all about making the bestseller list.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

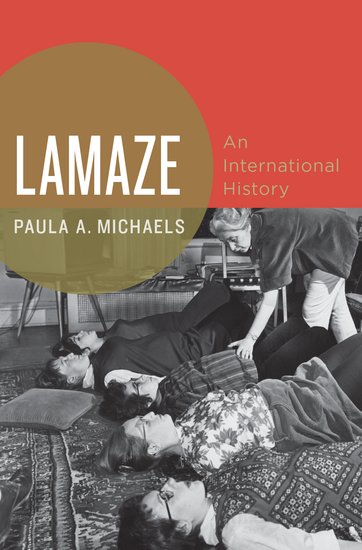

Paula A. Michaels is Senior Lecturer of history and international studies at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia and is the author of Curative Powers: Medicine and Empire in Stalin’s Central Asia and most recently Lamaze: An International History.

Disclosure statement: Paula Michaels does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

![]()

I am all in favour of studying the history of medicine in the Soviet Union. We are unlikely to see such work from Russian historians that meets our scholarly standards or engages with our interests. Just as they ignored Paul Alexander’s work on the plague, which threw a great deal of light on Catherine’s bureaucracy, so too they will ignore this. That does not mean to say that it will be of no use to Western Russianists, and especially those whose inquisitiveness is no longer under the shadow of the Cold War.

I work on a similarly arcane field, in an earlier period, but several of my essays are cited far beyond my own subdiscipline, or even the discipline of history. They are cited by nurses, doctors and epidemiologists, by sociologists, anthropologists, and literary scholars. They are cited in Czech, French, German, Russian, Spanish, and Catalan, among other languages. Yet I write only for historians of medicine, and some adjacent subdisciplines.

The same might well be true of many historians of medicine who are far more prolific than I have ever been.

I am even cited on websites written debunking The Da Vinci Code, in library guides, and by Wiccans calling for a more nuanced history of magic. However, I have never been constrained by the imperative for public outreach, imposed on so many British historians, or the quest for funding.

If armed forces, which are lavishly funded, exist to protect a culture, historians and other scholars of various kinds are the curators and explorers of that culture, without which it will wither on the vine.

[…] Okay, once more to the academic vs. popular history […]