By Robyn Elton

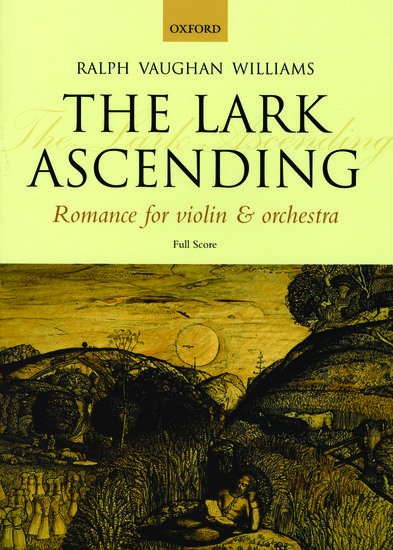

On Saturday 7 September 2013, lovers of classical music will gather together once again for the final performance in this year’s momentous Proms season. Alongside the traditional pomp and celebration of the Last Night, with Rule, Britannia!, Jerusalem, and the like, we are promised a number of more substantial works, including Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms and the overture to Wagner’s The Mastersingers of Nuremberg. I suspect the crowning glory for many listeners, however, will be Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending, performed by Nigel Kennedy—one-time enfant terrible of the violin world.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Kennedy’s earlier performance in this year’s Proms season could hardly have been less conventional. His late-night Prom with the Palestine Strings and members of the Orchestra of Life revisited Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons—the work he recorded to great acclaim nearly 25 years ago—but with a twist: this time the musicians added improvised links between the sections, fusing the Italian Baroque with jazz and microtonal Arabic riffs. Given this precedent, along with Kennedy’s reputation, I can’t help wondering what he has planned for his Last Night performance.

There’s certainly a lot of scope for personal interpretation within The Lark Ascending. Although Vaughan Williams is specific about his requirements on the page, the solo writing is calling out for a violinist to breathe life into it—to make the lark ascend, as it were. It must sound natural, almost as if it was improvised (as the lark’s song), leaving the door open for all kinds of interpretive inventiveness. In fact, I’d say that this is one of the main challenges for the performer, because to play this music ‘straight’ would be to completely take away its character. The composer makes his intentions in this area clear from the outset, with the opening cadenza notated entirely freely, without barlines and with senza misura marked not once but twice.

When I was 16, and again a few years later, I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to perform The Lark Ascending with orchestra—a rare chance for a young performer, and an experience I haven’t since repeated. The freedom of the work’s opening was exhilarating, yet in my case somewhat terrifying. You really are left hanging, when the already sparse orchestral accompaniment (just a held chord in the strings) drops out, leaving the soloist stranded at the extreme end of the violin’s upper range. With no orchestral support, there really is nowhere to hide, but on the other hand, you know you can take your time and everyone will just have to wait. For me, there was no way to practise exactly how that part would turn out on the night—no point in counting imaginary beats or planning the precise amount of bow to save. It’s all in the moment, and you can decide what you want to do at that very point in time, depending on how the mood takes you, the atmosphere in the hall, or even what your fingers feel like doing: it’s as if time is suspended. I can imagine that’s something that appeals to Nigel Kennedy, and I’m sure he’s on the exhilarated rather than terrified end of the spectrum.

After that initial cadenza, I almost felt like my work was done: I could relax and enjoy the sumptuous melodies to come (Vaughan Williams was especially kind in his first main melody—nothing too tricky there). Even the double stopping at the Largamente, the alternating parallel fifths, and the seemingly never-ending runs and twiddles, seem relatively harmless once you’ve conquered the opening. Of course, the cadenza returns at the end of the work (as well as briefly in the middle), and the soloist is once again left to wrap things up on their own. I just hope the excitable Last Night audience will be able to hold that moment of silence for long enough before bursting into rapturous applause.

Robyn Elton is Senior Editor in the printed music department at Oxford University Press and an active local violinist.

In the fifty years since his death, Vaughan Williams has come to be regarded as one of the finest British composers of the 20th century. He has a particularly wide-ranging catalogue of works, including choral works, symphonies, concerti, and opera. His searching and visionary imagination, combined with a flexibility in writing for all levels of music-making, has meant that his music is as popular today as it ever has been.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Image credit: Violin via Shutterstock.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.