By D. Gareth Walters

It is apt that Spain’s best-known poet, Federico García Lorca, should have been born in Andalusia. Castile may claim to be the heart and the source of Spain, both historically and linguistically, but in broad cultural terms Andalusia has become for many non-Spaniards the very embodiment of Spain. Lorca’s poetry abundantly reflects this perception. His work is imbued with the Andalusian ‘deep song’ (cante jondo), more ancient in origin than the gypsies who were its performers. Among his poems are pieces that have the authentic flamboyance and violence of image of the native art. Yet for all the showiness, there is unfailingly a sense of rigour. Lorca’s abilities as a musician, allied to an almost scholarly interest in the songs and culture of Andalusia, led to a profound understanding of the poetic potential of the region. Above all, his poetry evokes rather than describes. His realizations of landscapes and experiences are elemental, not naturalistic; he reaches to the roots of objects and feelings.

In the light of such an apparently instinctive and intuitive understanding it might be believed that Lorca was a born poet, someone for whom the task of writing poetry would be second nature. Poetry, however, was a second vocation. Lorca was primarily a gifted musician: a talented pianist and an accomplished composer. Only when his musical ambitions were thwarted — partly by parental opposition, partly by the death of his teacher — did he embark on a career in literature. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty he wrote thousands of lines of verse, much of it of mediocre quality. (Although this poetry has now been published Lorca himself wisely never wished to do so.) This was a necessary apprenticeship: a means of purging himself of the merely derivative, of what comes across as second-hand emotion. In particular, he emerged from the process with a leaner, sharper style that characterises much of his poetry of the 1920s: Suites, Poem of the Cante Jondo, Songs, and Gypsy Ballads.

Lorca did not travel widely outside Spain; indeed, for many years he divided his life between the family home in Granada and the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, an informal college where he got to know Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel. His visit to America in 1929-30 was therefore exceptional. The fruit of his stay was Poet in New York, a surrealist-tinged collection of poems where an angry denunciation of the modern metropolis is combined with an anguished sense of identity. It is all too easy to read the poems in terms of a culture shock: the naïve Andalusian adrift in a great city. Yet, the sophistication and the rhetoric of its indignation suggest that this is Lorca’s most international work, one that sits alongside the dystopian visions of the city and the masses that were common in Anglo-American writers in that period.

Lorca’s achievement is multi-dimensional in its nature. If he has become the most representative poet of Spain it is just, because he epitomises a sense of a history of Spanish poetry — both its popular and learned components. His uncanny sense of rhythm makes the most familiar forms, notably the ballad, appear new, endowed with a protean, sinewy quality. Such compositions thus seem timeless, which is why his poetry could never become dated.

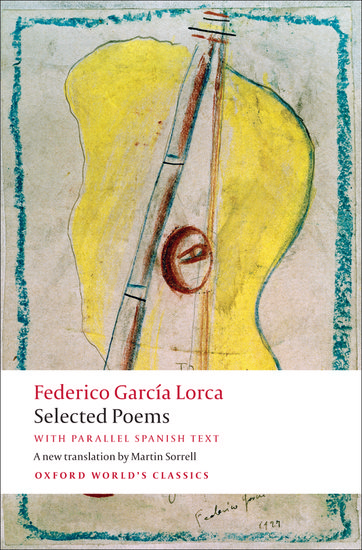

D. Gareth Walters has held chairs at the universities of Glasgow, Exeter, and Swansea. He is the author of numerous studies on Spanish literature including Canciones and the Early Poetry of Lorca: A Study in Critical Methodology and Poetic Maturity and The Cambridge Introduction to Spanish Poetry: Spain and Spanish America. He also edited the Oxford World’s Classics parallel text edition of Lorca’s Selected Poems.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bust of Federico García Lorca in Santoña, Cantabria. By Pere Joan Barceló [Public Domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.