By Robert Gildea

May ‘68 is often used as a shorthand for the protests and revolts that took place in that year, conjuring up images of barricades and Molotov cocktails in the Latin Quarter of Paris. But 1968 did not take place only in one year; it began in the mid 1960s and went on deep into the 1970s. Neither was it restricted to Paris; things happened from Madrid to Leningrad and from Copenhagen to Athens. It was a real European revolution – or was it? Europe was divided by the Cold War and between democracies in the north and dictatorships in the south. And activists did not always share the same ideas. When West German student leader KD Wolff attended an international youth festival in Sofia in 1968, he was appalled by the naïveté of the Czechoslovak activists who seemed to understand nothing about Marxist revolution. “You couldn’t talk to them. They were stupid,” he recalled. “They said ‘Freedom of the press! Dubcek is our man!’ Boring you know.” However, Polish activist Sewewrn Blumensztajn didn’t understand the West German militants either. He lived in a communist state and didn’t like it. “For us democracy was a dream,” he reflected, “but for them it was a prison.”

Activists encountered each other all over Europe in the years around 1968. They travelled for their studies to France, Italy, or West Germany and to summer camps for young communists in East Germany or for young anarchists in Switzerland. They fled from Franco’s Spain or from Greece after the 1967 military coup as political exiles. Sometimes they just showed up as revolutionary tourists in Berlin or in Paris for May ’68. The Iron Curtain was a barrier but it was porous in part and they shared a similar history. Their parents had resisted Nazism or fascism in the Second World War, or had not, and were either to be imitated or hated. They had a common hatred of imperialism, whether American or Soviet, and loved Mao, Ho Chi-Minh, and Che Guevara. In many ways, however, they failed to understand each other — not only over communism but also over consumerism, which was despised by Western militants but craved in the East. Time did bring them closer together. Some West European Marxists became disillusioned with Marxism and Third World revolution in the 1970s and were impressed by the struggles of East European activists against Communist totalitarianism. Scorn turned to admiration.

Activists wanted not only to change the world but to change themselves, and this too changed over time. When they met obstacles in one sphere and the authorities clamped down, they rethought and reworked their strategies for another opening. Even in the West, Marxism and anarchism were only two options: 1968 gave rise to feminism, gay rights, and men’s groups. The nuclear family came under attack and experiments in communal living proliferated from London to Leningrad. Liberation theology was born and base communities sprang up in conflict with established churches. 1968 generated radical plans to reform prisons and to turn psychiatric hospitals inside out, forcing a rethink of who was mad and bad, who good and sane. Many activists came out of 1968 with a sense that they had burned their fingers on political violence or hedonism. Others were more upbeat. “I don’t look back nostalgically to that 1968 moment,” says British activist Jeffrey Weeks, “I actually see it as having opened up possibilities, which are still continuing.”

Robert Gildea is Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford. He was a Lecturer at King’s College London (1978-79) and Fellow and Tutor in History at Merton College Oxford (1979-2006). He is a Fellow of the British Academy. He is co-editor, with James Mark and Annette Waring, of Europe’s 1968: Voices of Revolt (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

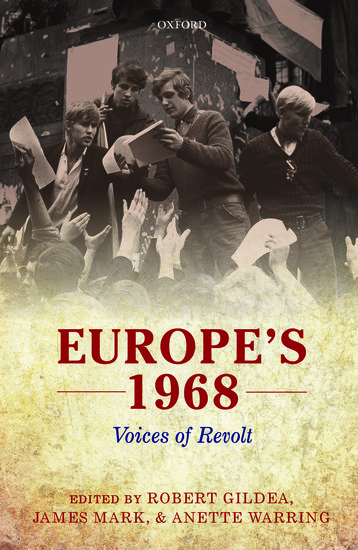

Image credit: Feminist group in France, 28 March 1971. Used with permission of Catherine Deudon, from ‘Un Mouvement a soi. Images du Mouvement des Femmes, 1970-2001’.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.