By Christina Simmons

Ninety-six years ago, on 16 October 1916, Margaret Sanger opened her first — illegal — birth control clinic in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. Human efforts to control fertility are at least as old as written history; ancient Greeks and Egyptians used spermicidal and barrier methods. But Sanger’s action began a new phase. In less than two weeks police shut the clinic down, but the incident heightened the visibility of the fledgling birth control movement. Sanger and other radicals like Emma Goldman had been claiming sexual freedom for women. They rejected patriarchal control over women’s sexuality; they thought only love, not convention, should guide sexual relationships and that women had the right to control their pregnancies.

Political battles over birth control in Sanger’s time engaged central feminist questions still at issue in US politics — namely, whether women may exercise the sexual autonomy customarily allowed to men. Recently, we have seen political struggles over health care regulations that require all employers, even institutions whose religious sponsors oppose it, to provide contraceptive insurance coverage. It is sadly indicative of rightwing desires to control women and sexuality that a panel of male representatives of conservative religious groups testified in Congress last winter about this question. They managed to make the issue about their religious liberty to deny contraceptive coverage to employees rather than about the religious liberty of women employees to choose birth control. Conservatives hoped to maintain, in one of the arenas they still control, the patriarchal ideology that had once forced access to contraception underground.

Political battles over birth control in Sanger’s time engaged central feminist questions still at issue in US politics — namely, whether women may exercise the sexual autonomy customarily allowed to men. Recently, we have seen political struggles over health care regulations that require all employers, even institutions whose religious sponsors oppose it, to provide contraceptive insurance coverage. It is sadly indicative of rightwing desires to control women and sexuality that a panel of male representatives of conservative religious groups testified in Congress last winter about this question. They managed to make the issue about their religious liberty to deny contraceptive coverage to employees rather than about the religious liberty of women employees to choose birth control. Conservatives hoped to maintain, in one of the arenas they still control, the patriarchal ideology that had once forced access to contraception underground.

In Sanger’s time political and religious authorities were outraged by her challenge and labeled birth control as part of a dangerously radical rebellion against marriage and motherhood. Sexually independent women might not marry; they might not center their lives on motherhood; or they might want to leave sexually unsatisfying marriages. As Linda Gordon has argued, however, the decline of the political left, as well as Sanger’s increasing desire to get something practical achieved to help ordinary women, led Sanger and other middle-class supporters of birth control to less inflammatory rationales by the 1920s and 1930s. Their later rhetoric downplayed women’s sexual freedom and argued instead that contraception would support the health of mothers and improve marriage relationships.

Birth control advocates faced what radicals in many times and places have faced: hostile laws and authorities but also the difficulties ordinary people have in acting on new ideas that unsettle social conventions and provoke antagonism. Sanger, for instance, had no luck through the 1930s with a frontal attack on existing law, which would have required members of Congress to stand up against traditional religious authorities (and voters) who still feared birth control was immoral. (Instead, a crucial federal court decision in 1936, United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries, opened the way for physicians to prescribe contraceptives.) Ordinary women on the other hand clearly wanted birth control, as attendance at the growing number of clinics in the 1920s and 1930s showed. But publicly proclaiming and openly acting on women’s right to sexual independence through birth control — especially single women’s — remained difficult. In an era when women’s employment paid very little and women’s most respected identity centered on wife- and motherhood, most women needed and wanted to marry. It was how they earned their living. To engage publicly in sexual relationships as a single woman was socially and morally risky to one’s marriage chances; those who did so were usually part of radical and bohemian circles.

In these circumstances, justifying birth control as part of motherhood and marriage was a safer ideological strategy, one that Sanger herself tried with her 1926 book, Happiness in Marriage. At the same time, others were also discussing marriage in a new way. Reformer Judge Ben B. Lindsey provided a new term when he published his 1927 book, The Companionate Marriage. Lindsey originally intended the label to mark an early, childless phase of youthful marriage; he argued it would allow couples to make sure they were compatible before launching into parenthood. However, the term can be applied more broadly to what liberal reformers were calling for in the 1920s — a modern form of marriage that included birth control, assumed smaller families, and was based more fundamentally on sexualized intimacy than Victorian marriage.

The 1873 federal Comstock Law had included contraception in the definition of obscenity, labeling non-reproductive sex as criminal as well as immoral. Rejecting this negative view, 1920s marriage reformers borrowed radical rhetoric condemning sexual repression and rehabilitated non-reproductive sex as healthy and natural. Women’s recent success in gaining the vote in 1920, as well as their agitation for birth control and other causes, brought a feminist tone to the discussions, emphasizing women’s right to sexual pleasure. Yet this recuperation of sex by companionate marriage advocates always led back to marriage. They wanted to sexualize marriage in order to save it. Using birth control to improve marital sex and to space children was one way to do that.

Advice works on how to live out modern marriage, including its sexual aspects, flooded onto the market in the 1930s, following court decisions which allowed the importation and sale of books with serious and scientific, as opposed to prurient, discussions of sex. Books such as British birth controller Marie Stopes’s 1918 Married Love could finally be sold in the United States. Most advice advocated contraception, but only after the 1936 One Package decision could works like Drs. Hannah and Abraham Stone’s A Marriage Manual provide explicit descriptions. Most books recommended Sanger’s method — the diaphragm with spermicidal jelly — as most reliable.

The economic crisis of the Great Depression did much to moderate opposition to birth control as desperate couples sought to limit pregnancies, and many women bought over-the-counter, often ineffective, “feminine hygiene” products covertly marketed as birth control. The Army finally provided condoms to soldiers in World War II. But the definitive US Supreme Court decisions striking down anti-contraceptive laws did not come until 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut (for married couples) and 1972 Eisenstadt v. Baird (for the single). From the opening of Sanger’s clinic until the 1960s, many American women read about birth control in marriage manuals and could most easily obtain it when engaged or married. Only in second-wave feminism did women again claim in widespread public ways that all women, single or married, had the right to birth control.

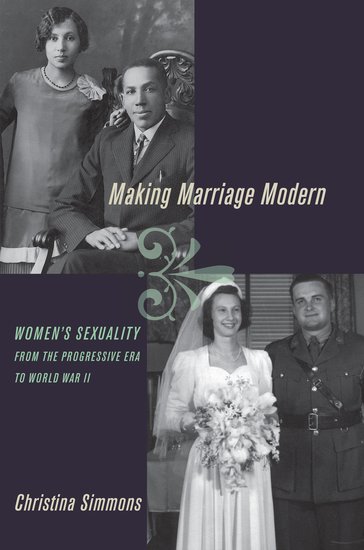

Christina Simmons teaches history and women’s studies at the University of Windsor, in Windsor, Ontario, and is the author of Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Image credit: Margaret Sanger, 1922. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division via Wikimedia Commons.

[…] When I was thinking about this time in my life, I remembered that in one of the SC exercises the plenary room was decorated with images from the 1960s onwards, charting the introduction of the Pill, the Lady Chatterley case, developments in reproductive technology, and the first civil partnerships and same-sex marriages. As a strategy, this gave participants the impression that ‘change’ in human sexuality was something recent, something restricted to our lifetimes which only we, of all human generations, have had to face. Of course, this isn’t true; change is normal, as any historian will tell you. Try, for example, just for the early twentieth century this link or this one. […]