By George Cotkin

Moby-Dick is alive and doing quite well. It serves as inspiration for cultural creation of all sorts. As much an adventure story as a metaphysical drama, the novel raises questions about the nature and existence of God, about the quest for knowledge, about madness and desire, about authority and submission, and much more. Its style, at once bold and impassioned, erratic and windy, somehow still manages to entrance and inspire readers a century and a half after its publication. It is, as critic Greil Marcus remarks, “the sea we swim in.”

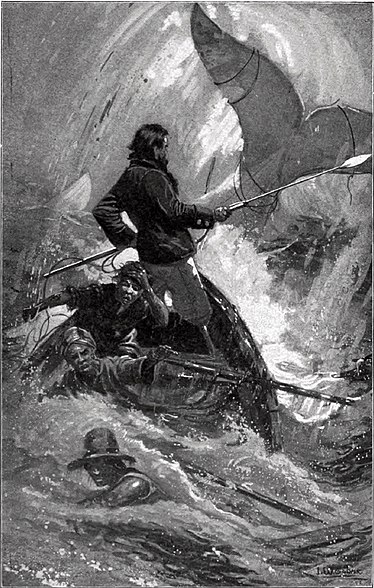

Don’t, however, confine the influence of the novel and its characters — a mysterious White Whale, a maniacal captain Ahab, a loquacious shipmate Ishmael, and his friend, the harpooner and divine savage Queequeg — only to the realm of literature. Moby-Dick has been, and continues to be, inspirational for film, art, and as an enduring source for metaphors and comedy routines. It has become as much a part of American popular culture as hamburger and Walt Disney productions.

The first motion picture version of Moby-Dick in 1926 was a silent, starring Lionel Barrymore. Forget about the whale vanquishing Ahab. In this film, Ahab — although he is dismasted — gets both the girl and the whale. Many other renditions of the novel in film followed. Perhaps the most famous was directed by John Huston, co-written by Huston and Ray Bradbury, and starring Gregory Peck as Ahab. Although Peck hardly sizzled with Ahab’s philosophical gravitas, the film did challenge polite 1950s codes about racial relations and hinted at blasphemy. A more recent film version, 2010: Moby Dick may strike Moby Dickians as blasphemous in its own manner. Renee O’Connor (once Gabrielle on the hit television show Xena: Warrior Princess) plays a scientist who is the only one that lives to tell the tale of a massive white whale, capable of flight, that once ripped a submarine in half and caused a Navy officer to lose his leg!

Almost no American artist of note — from Jackson Pollock to Rockwell Kent, Mark Bradford to Red Grooms — has failed to rise to Melville’s challenge that the White Whale shall remain “unpainted to the last.” Two years ago, an amateur artist of talent named Matt Kish, completed a project inspired by the book. Each day, on a piece of found paper, he made a drawing based on a single page from his Signet edition, for a total of 552 drawings! In addition to artists, composers and songwriters as varied as Laurie Anderson, Bob Dylan, Bernard Hermann, Jake Heggie, and rapper MC Lars have danced to its rhythms. Can we forget Dylan’s Captain Arab who alights upon the shores of America in surrealistic fashion?

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

Abbott and Costello had a comedy routine featuring the White Whale, certain that its popularity was deeply ingrained in the American popular imagination. Says Costello to Abbott, at one point in their repartee, “It’s a spout time you keep your mouth shut.” Phyllis Diller referred to her obese mother-in-law as ‘Moby Dick.’ Since 1942, youngsters have gained entry into the marvels of the tale via Classics Illustrated Comics, as well as commix versions, one of which was drawn by Sam Eisner. Sam Ito has made a marvelous Pop Up version of Moby-Dick, with moving parts.

The novel offers an endless stream of metaphors and meanings. Imprisoned members of the Baader-Meinhoff terrorist group used the names of characters to mask their identities. Political strategist Karl Rove once complained that a bunch of Ahab-like democrats pursued George W. Bush as if he were the White Whale, and Edward Said in the wake of 9/11 warned Americans away from seeking vengeance as Ahab had against the Moby Dick.

Gay critics and artists have long been drawn to Moby-Dick for the homoerotic relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg, and how Melville (who was probably bisexual) was willing in this novel to break with literary expectations to dive deeper into his talent and soul. Forget about the dearth of women characters in the novel. Sena Jeter Naslund created a story about an adventurous young woman that was Ahab’s wife, while Christian author Louise M. Gouge, in three volumes, not only imagines Ahab’s wife, but has his son fall into a state of sin, save the life of Starbuck’s son, lose his leg, and then be redeemed.

Where Moby-Dick will be in 100 years is impossible to predict. But its evolution indicates that what we today find meaningful may someday be seen as peripheral. In the early twentieth-century, Ishmael was often shunned as a problematic narrator and uninteresting character. A Knopf 1926 abridged version of the novel deleted what is now often considered the most resonant, or at least recognizable, first sentence in literature: “Call Me Ishmael.” That line, that clarion call into a novel of adventure, is now so embedded in our culture that cartoonists have employed it as a pick-up line used by guys in a bar, or shown Melville at writing desk, struggling to start his novel. Strewn around him are discarded pieces of paper with the words, “Call Me Larry,” or “Call Me Al.”

Moby-Dick lives, as Nathaniel Philbrick has noted in Why Read Moby-Dick, because it captures the American “genetic code” of concerns and conceits. It also contains so many elements of a great novel; one could mine its pages for years without exhausting its meanings. Finally, the novel endures because it lives fully in all the nooks and crevices of American popular culture.

There is no indication of that changing anytime in the near future.

George Cotkin is Professor of History at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, and author of the forthcoming book, Dive Deeper: Journeys with Moby-Dick.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Moby Dick Lives […]

[…] ένα κείμενο στα αγγλικά από το σάϊτ των εκδόσεων της […]