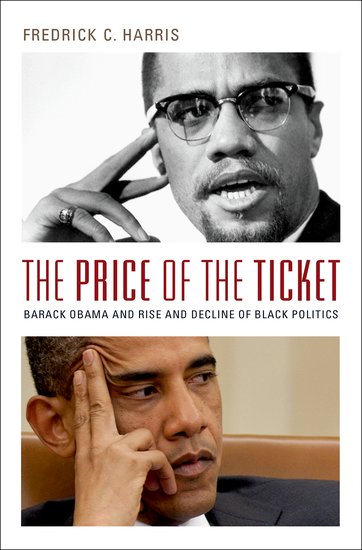

Dr. Fredrick C. Harris is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society (CAAPS) at Columbia University. He is the author of several books, including his latest, The Price of the Ticket: Barack Obama and the Rise and Decline of Black Politics. In it, he argues that the election of Obama exacted a heavy cost on black politics. In short, Harris argues that Obama became the first African American President by denying that he was the candidate of African Americans, thereby downplaying many of the social justice issues that have traditionally been a part of black political movements. In this interview, Harris discusses his findings with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You write that President Obama’s campaign and subsequent victory helped to sap the civil rights movement of its militancy, and that social justice issues traditionally associated with black politics have been marginalized. This is the “price of the ticket.” Was it ever possible for a traditional civil rights leader to win the White House? Or was it inevitable that the first black President would be a so-called “post-racial” politician from Generation X or beyond?

Fredrick C. Harris: No, it was never possible for a traditional civil rights leader to win the White House, nor was it possible for any race-conscious black politician to build a broad coalition of voters to support their candidacies. Though Jesse Jackson’s run for the Democratic Party nomination in 1988 came closer than any other black person before Barack Obama’s rise as a presidential candidate. But the idea of a black president and the importance of black voters pushing an agenda that would include both universal policies and policies specific to black communities are two separate — though not necessarily exclusive — political goals. For instance, both Shirley Chisholm’s run for the Democratic nomination in 1972 and Jesse Jackson’s run in 1984 were efforts to place issues that were important to black voters on the electoral agenda. As a means to bring the concerns of black communities to the attention of the Democratic Party, both the Chisholm and Jackson campaigns altered the party so as to not take black voters for granted.

What we see with the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first black president is the tension between the politics of symbolism and a substantive-focused, agenda-specific politics that includes both policies “that benefit everyone” as well as targeted public policies that focus on uprooting the persistence of racial inequality. These divisions in policy approaches to racial inequality and in the belief in the utility of race-neutral campaigning and governing have, I believe, less to do with generational differences in black Americas but more to do with ideological fissures in black politics about the best way for blacks as a group to attend to the ongoing problem of racial inequality.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You make clear the relationship between Barack Obama’s rise to power as a “race-neutral” candidate, and the rise of what is known as the Prosperity Gospel among black voters. (By Prosperity Gospel, we are referring to the theology of financial and physical empowerment through spiritual exercise and self-reliance; this is a distinct departure from traditional black liberation theology, which places greater emphasis on attacking racist power structures.) Can you expand on the connection between the two? And is this a trend that you expect to grow stronger over the next generation?

Fredrick C. Harris: The concept of deracialized political campaigns, which emerged during the 1980s and 1990s when black politicians were trying to break the glass-ceiling by running for high-profile offices in majority white jurisdiction, supports a color-blind approach to politics. By downplaying race in campaigns — especially by avoiding discussions of race-specific policy issues — race-neutral black politicians become symbols showing that Americans have gotten beyond race. These symbols of black progress reinforce the widespread, false belief that few barriers prevent African-Americans from succeeding in American society.

Perhaps in subtle ways, adherence to the prosperity gospel provides a theological justification for the kind of color-blind black politics that is promoted by race-neutral black candidates. In many ways, the prosperity gospel is a color-blind theology. Unlike the long-standing social gospel tradition — that focuses on the duty of Christians to uplift individuals as well communities — and black liberation theology — a theology that emerged during the Black Power era and focused on the idea that a black God commands his followers to attend to the needs of the oppressed—the prosperity gospel is centered strictly on transforming individuals, not transforming communities. Only negative beliefs and thoughts about one’s station in life — not social barriers — prevent believers from receiving God’s material blessings. This implicit color-blind take on theology mends well with a politics that sees race having little or no effect on the ability of black people — particularly poor and working-class black people—to progress. Thus the growing popularity of a theology among black Americans where race does not matter and the acceptance of a style of politics that communicates the message that race does not matter as well, is, I would argue, weakening — if not the death — of a tradition of politics that confronts racial inequality head-on.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: You write, “The ‘slack’ that black voters gave Obama…meant that black voters put aside policy demands for the prize of electing one of their own to the White House.” Can you discuss a particular opportunity that Obama missed (or rejected) that would have specifically helped to alleviate the issue of black inequality?

Fredrick C. Harris: There are several, but at least one particular opportunity comes to mind during the 2008 campaign—specifically the Jena Six controversy. As you recall six black male teenagers were charged with attempted murder for fighting in a schoolyard brawl in Jena, Louisiana in 2007. What is curious about this moment is that Obama did rise to the occasion by giving an address on race and criminal justice reform during Howard University’s Convocation on September 28, 2007. The candidate seems to have been pressured to talk about the accident — as were all the major Democratic candidates for president — and outlined policies he would support to ameliorate racial disparities in the criminal justice system. One initiative Obama promised was to support a federal-level racial profiling act. That promise has yet to come to fruition, and Obama has not publically discussed the need for such an act since he’s been president. Two incidents — in theory — provided an opportunity for activists to press the president on racial justice reform, and for the president to follow through on his promise — your arrest in the summer of 2009 by Sergeant Crowley of the Cambridge, Massachusetts police force, which galvanized national attention, and the murder of Trayvon Martin earlier this year, which has again raised questions about the deadly consequences of racial profiling. Though the president expressed sympathy for the victims in both cases, Obama has yet to follow through on his campaign promise on reforming the criminal justice system.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: If, as you suggest, Obama’s presidency is in many ways a victory of the status quo (despite its appearance as a new era in racial politics), then why has the reaction to him among conservatives been so hyperbolic and hysterical, from questioning his citizenship and religion to accusing him of being a socialist?

Fredrick C. Harris: Yes, race still matters for black public officials in high-profile positions. One would expect no less for the nation’s first black president. But the attacks on Obama are also equally partisan in nature. Because Americans have such short memories about elections and presidential administrations, those who complain of Obama’s treatment by the Right forget that Bill Clinton was accused as a sitting president to be a rapist, a murderer, and a cheat. Clinton was dogged by the federal prosecutor Ken Starr and impeached by the Newt Gingrich-led House of Representatives. Indeed, Clinton’s treatment in office by the Right led Toni Morrison to declare that Clinton was the nation’s first black president. Since Republicans are so effective as an opposition party and so ineffective in governing, their nasty opposition to Obama (as well as former House speaker Nancy Pelosi) is merely a continuation of the “politics of destruction” during the Clinton years.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: Do you foresee a similar “Price of the Ticket” for other marginalized groups (women, GLBT, religious minorities) if and when they have a representative in the White House? Or is this problem you describe unique to the African American experience?

Fredrick C. Harris: That is an interesting question. Often one of the burdens of stigmatized minorities is to proclaim and to demonstrate to those in power that their stigmatized identities will not make a difference in how they view those in power as well as the levers of power. Such proclamations are required for entrance and acceptance into mainstream life. In 2009, there were echoes of the openly gay candidate for candidate for mayor of Houston — Annise Parker — deemphasizing her commitment to gay and lesbian issues and downplaying her long-time activism for gay and lesbian rights. She wanted Houston voters to know that she should be judged by her experience in maintaining the fiscal heath of Houston, as she had demonstrated as the city’s comptroller, not for her sexuality or he past commitments to gay and lesbian rights. When asked whether she would support a referendum to support same-sex benefits for city employees, which was rejected by voters in 2007, Parker responded that she did not have plans to endorse such a referendum. Parker won the election, becoming the first openly gay mayor of a major American city and, as a consequence, a symbol of gay pride. But she also has been of late — particularly since her re-election to the mayor’s seat this year — a strong voice in support of marriage equality. She also urged president Obama to evolve faster on that issue before Obama endorsed marriage equality. It is too early to see if GLBT public officials in the future will follow Parker’s “sexuality-neutral” campaign style she employed in her first election. However, Parker may have done a wink-and nod. She has become a strong voice of advocacy for the GLBT community’s causes, endorsing marriage equality and condemning right-wing homophobic elements in Houston. It will be interesting to see if Obama — like Parker has on GLBT issues — will become more vocal on racial equality issues if he is elected to a second term.

This interview originally appeared on the Oxford African American Studies Center.

Dr. Fredrick C. Harris is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society (CAAPS) at Columbia University. He is the author of most recently The Price of the Ticket: Barack Obama and the Rise and Decline of Black Politics. He is also the author of Something Within: Religion in African-American Political Activism, which was awarded the V.O. Key Prize for the best book on southern politics by the Southern Political Science Association, the Distinguished Book Award by the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, and the Best Book Award by the National Conference of Black Political Scientists. Dr. Harris is also the co-author (with R. Drew Smith) of Black Churches and Local Politics, and (with Valeria Sinclair-Chapman and Brian McKenzie) Countervailing Forces in African-American Civic Activism, 1973-1994, which won the 2006 W.E.B. DuBois Book Award from the National Conference of Black Political Scientists and the 2007 Ralph Bunche Award for best book in ethnic and racial pluralism from the American Political Science Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.